By Dimitra Gatzelaki,

The Renaissance stands, without a doubt, as an epoch of cultural innovation and flourishing creativity. Spanning from the 15th to the 17th centuries, it was characterized by a blooming thirst for progress, for a beacon of light to combat the “vast darkness” of the Middle Ages (which we nevertheless know today to be a misconception). Its interests progressively turned away from “absolute” medieval ideals, such as the divine right of kings and a strict form of religion, towards a more humanitarian way of thinking that embraced individualism, humanism, and the spirit of innovation. Art, science and philosophy all blossomed and thrived, as the period birthed some of the artists and thinkers immortalized in human history: da Vinci, Galileo and Shakespeare (to name a few).

Yet, amid this era of dazzling innovation, refined beauty and achievement, what role did women play? This neglected-yet-fundamental question was taken up by Joan Kelly in a 1977 essay, where she asked, “Did women have a Renaissance?”

In fact, they didn’t. As the Renaissance political system shunned medieval feudalism in favor of more complex city- and nation-states, the world also witnessed a shift in the relationship between the sexes. This relation, Kelly asserts, was “restructured to one of female dependency and male domination” (qtd. in Cloud, my emphasis). The role of women was scant: they were expected to be “seen and not heard” (Cloud). Their bodies were tools, and their will was an illusion. For half a century, England was under the rule of one of its most illustrious queens, Elizabeth I, the “Virgin Queen,” yet men were still the ones who held sway in all matters. It thus becomes clear that the Renaissance woman’s circumstances were still “tainted” by the influence of the Middle Ages.

However, we can also view this narrative through a different lens. While it’s true that women in the Renaissance weren’t understood or “seen” (in a figurative sense) any more than they were in the Middle Ages, they did indeed begin to be physically seen more; and in some cases even to express themselves, as per their husbands’ wishes, of course.

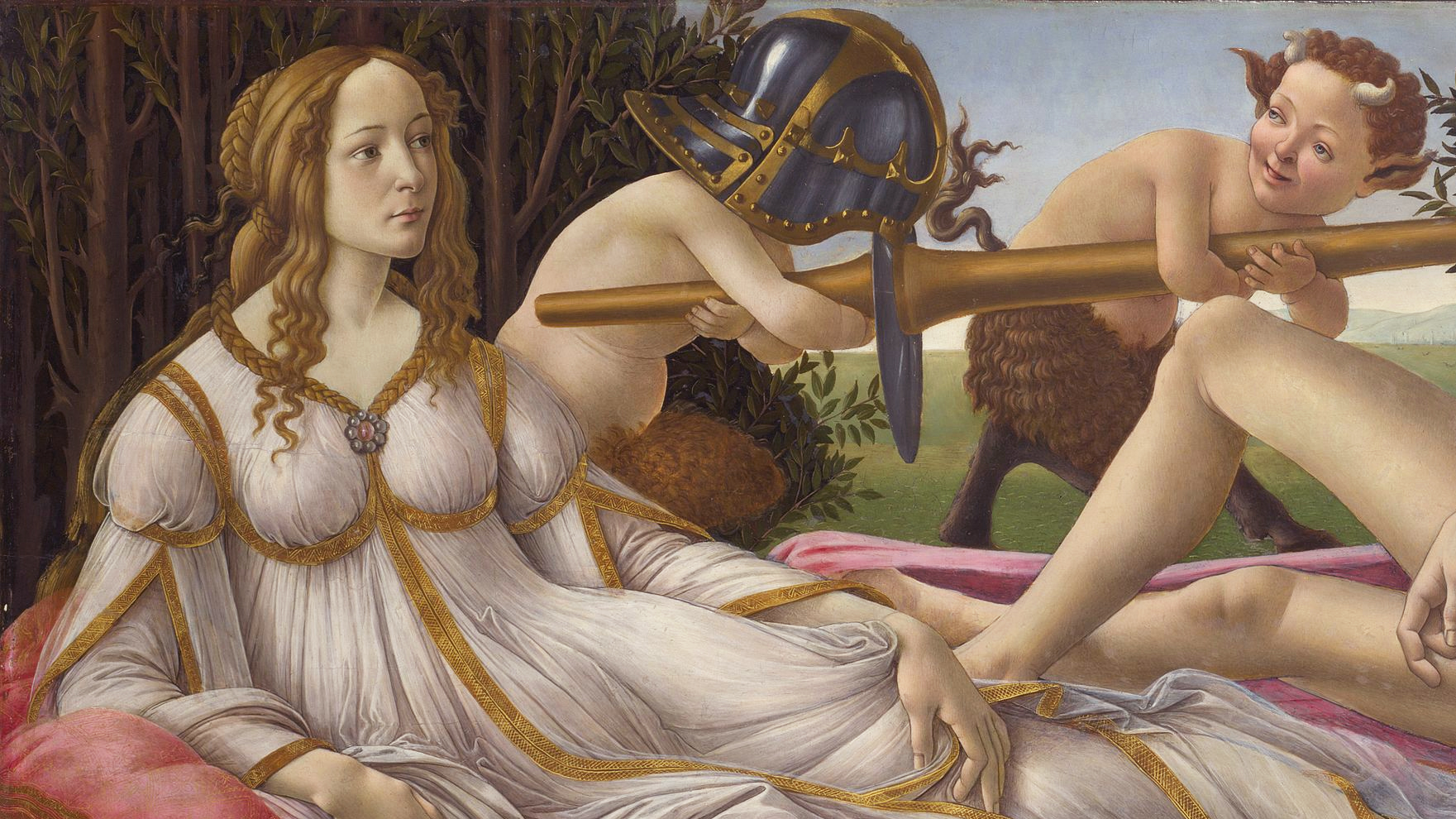

Moreover, art depicting women flourished: Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” is an exemplar of this. In his paintings, the female body stands opposite the beholder, graceful and alluring; she looks at us softly in the eye and asserts her presence. Botticelli’s art can furthermore be seen as depicting the subtle shift of the “ideal” female body toward “the hourglass figure favored by Greek and Roman sculptors” (Dunant). And precisely this idealized portrayal of the Renaissance woman in art is thought to have influenced society’s perceptions of beauty. In a sense, it paved the way for a new feminine aesthetic.

This novel “feminine ideal” of the Aphrodite-esque look may well be one of the reasons for the abundant innovations in beauty-related fields during the Renaissance. As Dalya Alberge mentions in their article, Renaissance women “were using beauty products that were far more sophisticated than previously thought” to achieve “beautification of the face, hair and body”. To illustrate the breadth and, at times, the extremes of these beauty practices, Alberge references the research of art historian Jill Burke, who delved into The Ornaments of Ladies by Giovanni Marinello, a 16th-century cosmetic manual. This assortment boasted “more than 1,400 recipes arranged in order of the body part to be corrected,” and Alberge further notes that “some writers urged their readers to make themselves look like women imagined by painters and poets, such as Titian and Petrarch – just as today’s women look up to idealized models in glossy magazines.” This is a compelling analogy indeed.

Contrary to the popular misconception that Renaissance cosmetics were poisonous, recent research, such as that conducted by Burke, debunks this myth. Burke’s exploration uncovered beauty recipes from the era, including “lip balm made with rose oil and grated beeswax simmered on a low heat, an eye cream of honey and egg crushed into an ointment and an exfoliator of breadcrumbs” (Alberge). Through experimentation with these recipes, Burke discovered that “most of what they used doesn’t contain ingredients that we now know are poisonous – and most of them actually do work.” This ultimately led her to conclude that Renaissance beauty practices possessed “a much higher level of knowledge and skill than we previously understood” (qtd. in Alberge).

While Renaissance beauty practices undeniably introduced pioneering innovations into women’s daily lives, with some enduring to this day, Dunant’s critique prompts us to take a step back and view the broader picture. She brings attention to the “age-old debate” reflected in Burke’s work, questioning whether women’s engagement with beauty signifies weakness, submission to male desires, or empowerment. In my view, the latter interpretation holds more weight. In an epoch where women were seen rather than heard and their voices were marginalized, their emphasis on appearance served as a means of asserting their presence in this limiting society. As Dunant aptly points out, borrowing from Burke’s analysis, “Renaissance women cared about what they looked like because… ‘they had to’”.

References

- Gender Roles of Women in the Renaissance. Cedar Crest College. Available here

- Crumbs and cat poo: Renaissance women’s ‘astonishing’ beauty tips revealed. The Guardian. Available here

- Shopping & Plucking: How to Be a Renaissance Woman: The Untold History of Beauty and Female Creativity by Jill Burke. Literary Review. Available here