By Katerina Taxiaropoulou,

“Learn from me, if not by my percepts, at least by my mistakes how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge”

—Mary Shelley, quote from Frankenstein

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word horror describes “a painful emotion compounded of loathing and fear; a strong aversion mingled with dread” (OED). Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein inspires horror with its exploration of the dangers of extreme scientific ambition, as well as the awful clash between science and humanity.

Written in 1818, Shelley’s novel is infused with elements from Gothic and Romantic literature, though it has also been characterized as the “first true science fiction story” (Briann Aldiss). Frankenstein tells the story of a ‘mad scientist’ named Victor Frankenstein who aspires to make life out of death, and so creates a monster that eventually kills him.

As a child, Victor first encounters and falls in love with a premodern form of science in his readings of Cornelious Agrippa, Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus. Although his father warns him that these authors represent alchemy, a dated system of knowledge comprised by occult materials of no scientific value, the young reader cannot help himself and goes on to consume a great number of similar books in secrecy.

Around puberty, however, disillusioned by alchemy’s inability to explain certain physical processes, Frankenstein turns to natural philosophy, a modern branch of science which had “the orthodoxy of a materialist and pantheist view of nature” (Markman). Hence, he decides to go to Switzerland in order to study natural philosophy in the university of Ingolstadt.

Inspired by one of his professors there, he becomes a model, goal-oriented student, spending endless hours reading books of chemistry, anatomy and physiology. Amidst all this knowledge hunting, he perceives the bold idea of collecting and stitching together dead body parts and giving life to a new man with the help of electricity.

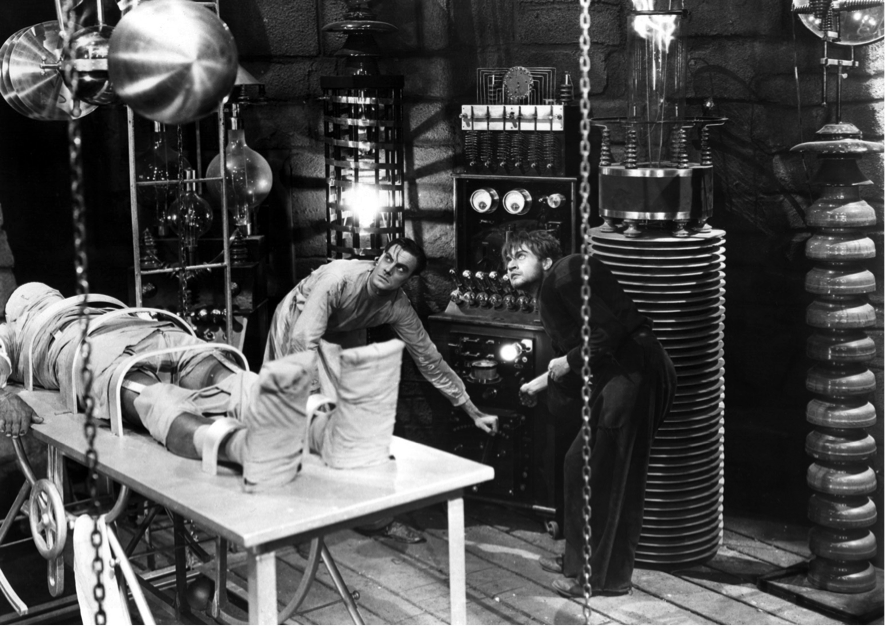

The creation experiment (film adaptation). Image source: sqonline.edu

The scene shifts from the university laboratory to the churchyard and from day to night. Victor becomes the grave-robbing anatomist, conducting his experiments in a solitary chamber. Finally, after months, an 8-feet-infant arises from his operating table, and he runs away in terror of its ugliness.

Alone and abandoned, the baby Creature needs to learn how to survive. First, he tries to go out to society but they hunt him down. Thus, he finds shelter in a forest cave, near to the house of a poor family. By watching them through a crack in the wall, he takes lessons of language, history and arithmetic.

After months of his voyeuristic study, he becomes knowledgeable and grows to love these people. So, he feels the need to help them in secret. He brings them wood, for the fire and does different chores around the house during the night. After all this good he has done, he hopes, they will accept him as part of their family. Yet, when he reveals himself to them, their reaction is the same as his creator’s: fear and hatred.

Following this incident, the creature is filled with sentiments of anger and vindictiveness, and so decides to destroy his creator’s life by killing everyone the later loves. From this point forward, dread spreads through the pages and readers’ hearts, compelled by a domino of cold-blooded murders which showcase how excessive scientific ambition can turn against not only the individual scientist, but also a whole community of innocent people.

Beyond the material dangers that scientific experiment conceals, the book also sparks a conversation about the less concrete, but equally terrifying reality of the scientist’s lost ethos.

In the story, social ideology about normality and ambitious scientific discourse on the perfectibility of human nature interact to perform an act of utter cruelty against the marked individual. Late 18th century physician Beddoes argued that we are “culturally conditioned” to judge as malevolent those that deviate from artificially determined standards of normality, so that we can justify immoral behavior against them (qtd. in Markman 112).

In an era of fast-pacing scientific and technological development, when there was extensive discourse on the evolution of the human species, the people of Ingolstadt viewed Frankenstein’s Creature, not only as an abhorrent beast, but also as a relic of the uncivilized past, a sign of regression. So, perceiving his abnormal enormity as a threat to progression, these people caused the yet infant Creature to flee the city, unapologetically forcing on him the challenge of survival in exile. With the same mindset, Victor, the scientist who brought him into life, abdicated all responsibility, once he saw that his progeny’s hideous form in no way lived up to the dominant neoclassical standards of harmony, crying that he had selected his features to be beautiful.

The overambitious scientist had set out to create the externally perfected, most physically advanced and sophisticated human being on earth, but the final product of his arduous work looked more like a vile savage to him, a thing 319, rather than human. In his abnormal appearance, he only saw “innate evil”, a marginal threat for the society (Markman 154). With this excuse, Victor simply abandoned his newborn creature to survive on his own.

The creature has lived a life of terrible loneliness, deprived of any sentiment of love or the simplest act of care toward his person. Although he desires happiness like every other individual, he bears no chance for it. So, the only think he can hope for is revenge. According to a younger generation of critics, the creature’s terrorism is “not the result of his inherent malice”, but the effect of his cruel ostracization by a society that judged him based on his physical appearance (Markman).

“I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.” (Mary Shelley, quote from Frankenstein )

As it appears, although Frankenstein was written in early 19th century, it is more relevant than ever. Within 166 pages of true horror narrative, anxieties regarding the fragile state of society are connected through the theme of modern science and its ambitions of perfectibility. As early as in 1818, Shelley points at the unforeseen consequences of transgressive scientific and technological change.

References

- Markman, Ellis. “Science, Conspiracy and the Gothic Enlightenment: Fictions of Science in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.” The History of Gothic Fiction, Edinburgh University Press, 2000, pp. 141-160.

- Purinton, Marjean D. “Chapter 8: The British Reception of Frankenstein (1818) and the Culture of Early Nineteenth-Century Science.” Mary Shelley and Europe−Essays in Honour of Jean de Palacio, Legenda, 2020, pp. 105-117.

- Frankenstein. britannica.com. Available here

- Horror. oed.com. Available here

- Aldiss, Brian. The Detached Retina. Syracuse University Press. 1995. Available here