By Maria Vrachneli,

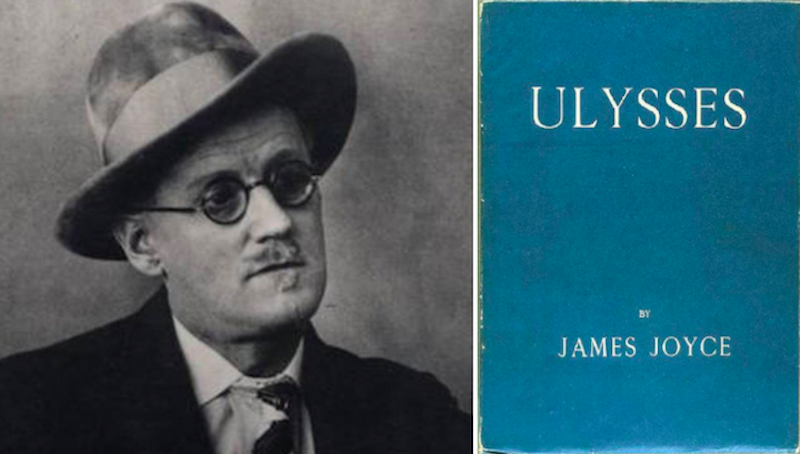

In Ulysses, James Joyce disrupts the conventions of realism and presents an experimental writing style that includes mixed narrations, outer dialogue, linguistic distortions, unusual or omitted punctuation, the stream of consciousness, memory flashes, and free indirect discourse. The purpose of this essay is to investigate the styles and perspectives generated by the different narrative techniques and explore their connotations and effects in the fourth episode of Ulysses’ “Calypso”.

In the opening scene of “Calypso” one of the main characters, Leopold Bloom, is introduced with “the most detailed scrutiny” (Slote vi), as the third-person narrator describes from an external point of view Bloom’s peculiar visceral dietary preferences. As Bloom “[…] liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, […] grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.” (U 43), the narration not only generates vivid imagery and, therefore, activates the senses of the reader, but also indicates the character’s socio-economic status – that of a “middle-class working man” (Parks 44,) who has the luxury of making uncommon, rather inexpensive food choices. As the episode unfolds, outer dialogue blends in with the third-person narrative.

While Bloom is carrying out his morning routine of preparing breakfast and feeding his cat, a conversation between the two interrupts the narrative. This interaction reveals the character’s benevolent nature, compels the reader to resonate with him, and as Tim Parks supports; “certainly he wins our hearts […]”. In the dialogue instances, Joyce also experiments with written representations of sounds and constructs a play on words as with the cat’s perceived utterance that evolves from a “– Mkgnao!” to “ – Mrkgnao!” and to “ – Mrkrgnao!” (U 43). A page later, this varied response, in comparison to that of Bloom’s wife, will function as a source of information for their relationship as “her sleepy ‘Mn’ (U 44) is meant to be compared, unfavorably, with the cat’s more generous “Mrkrgnao” (U 43).” (Parks 47).

While Joyce compensates for the rejection of quotation marks – which he called “perverted commas” (Slote viii) – by using “the 2-em dash (——) instead” (Sheehan 10) when portraying dialogues, he “does not signal transitions to a character’s thoughts […].” (Slote viii). Throughout the text, Joyce uses the stream-of-consciousness technique, shunting the reader into the characters’ minds to explore them without a mediator filtering their informative and depth-creating thoughts. As Liz Delf argues; “authors who use this technique are aiming for emotional and psychological truth.” When Bloom “gives his order quickly” (Blamires 25) at the butcher’s shop to catch up behind the neighboring girl and “take pleasure in the movement of her hips” (Blamires 25), Joyce assigns his character to expose his thoughts, indicating Bloom’s simple desires and his sex-deprived marriage, in an authentic and human-like way.

As the stream-of-consciousness technique grants access to the characters’ “fluid and stream-like […]” (Delf) thoughts, it also offers insight into the characters’ memories. Through this pervasive narrative, the reader dives into Bloom’s memories as his daughter’s letter triggers flashes of past events and experiences that as Ramona DeFelice Long states; “tells the reader important information necessary to fully understand the characters’ dynamics […]” and their relations in present time.

The unmediated narrative seeps into the third-person perspective with the use of free indirect discourse. Sam Slote highlights that when this technique is applied “the narrative perspective is […] extremely close to a character’s thoughts and it can only be distinguished from them through the choice of pronouns.”. As the narrator explains how Bloom’s “hand accepted the moist tender gland and slid it into a side pocket” (U 46) after getting his order from the butcher, it is as if the narrator is affected by the character’s immersion in his sexual fantasies, since this is a description with overly specific sensory observations and words tied to sexual connotations. With free indirect discourse, the reader gets closer to the characters’ point of view and – almost – subconsciously, makes them feel that they are part of the story. As Raymond Malewitz argues; “we (the readers) feel what they (the characters) feel in large part because we are momentarily seeing the world as they are seeing it.”.

In Joyce’s experimental writing in Ulysses, “the most formidable obstacle facing the reader […] is dealing with the ever-shifting styles and perspectives.” (Slote vii). Despite the challenge of navigating through them, after investigating their functions, they have proven to be essential for the flow of information that constructs multifaceted and, therefore, complete characters.

References

- Blamires, Harry. The New Bloomsday Book: A Guide through Ulysses. Routledge, 1996.

- Declan Kiberd, et al. The Book About Everything. Apollo, 2023.

- Joyce, James. Ulysses. Edited by Sam Slote, Alma Classics, 2017.

- Long, Ramona DeFelice. “How to Tell–Flashback or Memory?” Ramona DeFelice Long, 5 July 2012. Available here

- Sheehan, Sean. Joyce’s Ulysses. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009.