By Eirini Tassi,

In his 1993 essay “Anarchy is what states make of it: the social construction of power politics”, Alexander Wendt states that “There is no ‘logic’ of anarchy apart from the practices that create and instantiate one structure of identities and interests rather than another” (Wendt 1993: 394-395). This indicates that anarchy is inherently neutral. Wendt claims that the state system that arises from international anarchic conditions does not necessarily lead to a neorealist self-help order, but it is socially constructed based on the way states interact with one another (ibid.).

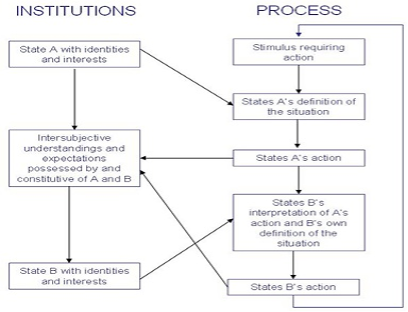

Wendt’s argumentation responds to neorealist scholar Kenneth Waltz, who supports that the international “self-help” system necessarily arises because in a state of international anarchy, and in the absence of a global, security-maintaining authority, states always wish to maximize their power relative to other states to survive (Wendt 1993: 395-398). Therefore, material conditions (power) explain the structure of the state system (ibid.). Wendt argues that concentrating on material factors is insufficient in explaining the relations between polities, because it ignores the socially constructed realities that one has for the other (ibid.). It is such norms that make a state to relationally perceive others as “friends” or “enemies”, and to treat them accordingly based on that label (ibid.). He empirically illustrates that through the US-Cuba-Canada relationship (ibid.). Although Canada possesses a stronger military than Cuba, and thus larger material power relative to the US, the US perceives Canada as a “friend”, while Cuba with greater hostility (ibid.). Hence, material conditions are not enough to explain state relations; even power is constructed by norms/ideas that states shape for one another upon their interaction.

Therefore, stating that “there is no ‘logic’ of anarchy apart from the practices that create […] one structure of identities and interests rather than another”, holistically encapsulates Wendt’s argumentation (Wendt 1993: 394-395) that Waltz’s self-help order is only one of many possible state systems that can rise from anarchy. This can occur through predatory states, who due to internal factors become aggressive in the international system (idem: 407). The possibility of such actors violating their own territorial sovereignty can trigger other states to aim for power maximization, since there is no global authority to protect them from potential attacks (idem: 407-408). Nevertheless, other outcomes are also possible; if states through their interactions can construct cooperation as their goal, this can lead to the development of a collective security identity as a mutual state interest, which can produce a cooperative rather than a self-help system (idem: 415-419). Therefore, anarchy is indeed what states make of it; their chosen practices, as the quote states, determine what kinds of identities and interests inform the structure of IR.

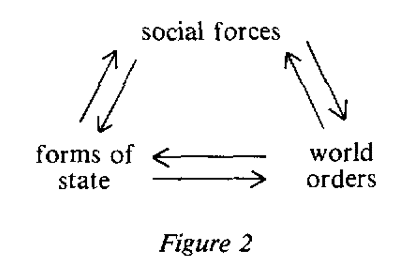

Wendt’s argumentation is largely in line with Robert Cox’s paper “Social forces, states, and world orders: beyond international relations theory”. They both see (neo)realism as a deeply unadaptable IR theory. In the same manner that Wendt points out that its bias towards material conditions impedes it from understanding the state system throughout time, Cox criticizes its “problem-solving”, ahistorical configuration: it takes the parameters of the current world order as a given, and therefore, in its dissection of global relations based on these parameters, it implicitly establishes this system’s order and its dominant actors as “the norm” throughout any type of historical trajectory (Cox 1981: 128-131). While this reflection on power dynamics does move closer to post-constructivism, both academics nevertheless agree that (neo)realist IR’s fixed self-help model that allegedly explains any state behavior, is deeply inflexible and unilateral. Moreover, in his response to realism and similarly to Wendt’s state-interaction model within global anarchy, Cox proposes a critical model, where social forces, specific state forms and whole state systems interact with each other to produce new IR dynamics (idem: 138-140). They both recognize that for such system changes to occur, the micro (social forces) can influence the macro (state and system) but the macro can also influence the micro. For example, Wendt’s predatory states can develop aggression through domestic conditions (micro), but can then shape the interests of fellow states as power-maximizing (micro) through their own hostile interaction with them (macro) (Wendt 1993: 407).

References

- Wendt, A. (1992). “Anarchy is what states make of it: the social construction of power politics”, International organization, 46:2, 391-425.

- Cox, R. W. (1981). Social forces, states and world orders: beyond international relations theory, Millennium, 10:2, 126-155.