By Eirini Tassi,

The witch-hunts of early Modern Europe undeniably sparked terror across the continent, with cases of mass-panics even subjecting a third of a region’s population to accusations, prosecutions, and executions. Salem, at the time an English colony, was also caught in the widespread witch panic, and claimed numerous victims in the infamous trials of 1692-93. From these unlucky suspects, one certainly catches one’s eye: George Burroughs, a young, Harvard-educated male pastor. This makes sense; in a Puritan, patriarchal Salem, how can someone who represents the status quo in every way find their fate in the hanging tree of accused witches?

A quick context: Tituba and the Devil’s conspiracy

Tituba, a native-American slave of Salem’s minister, was the first to be accused of witchcraft in Salem in early 1692, after the minister’s daughter and niece experienced fits that a physician appointed to “touch by an evil hand.” In her trial records on March 1st, she confesses to practicing maleficium (malevolent magic) upon the two girls, yet she attempts to deny her individual agency in these actions, by putting forward the possibility of a demonic conspiracy within Salem. In her interrogation by magistrate John Hathorne on whether she hurt the victims, Tituba argues that it is a male-dominated malicious group that pushed her to torment the children on its behalf. She calls their leader the Devil, and demonstrates how he and his subordinate women would threaten her to hurt the children or face worst torment by them if she refused. So much so, that the Devil would take zoomorphic appearances, like that of a great black dog, to intimidate her. She thus reconstructs the narrative of the “evil hand” that was tormenting the girls, not as a Devil spontaneously spreading afflictions in Salem, but one who strategically recruits members of the community to destroy it from within; a conspiracy rooted on the man, but ultimately committed by unsuspected “insiders;” witches.

Tituba’s portrayal of a collaborative evil conspiration is vital when observing the wider perception of the devil in Salem. At that time, there is a general belief that through witchcraft, Satan aims to overturn all elements of European society found in the English colony. Her testimony thus not only reaffirms such paranoia amongst Salem’s magistrates, but she undeniably sets the starting point from which all future accusations occurred. In Bridget Bishop’s testimony a month later, for instance, magistrate Hathorne repeatedly asks her who her master is, appearing to have been influenced by Tituba’s narrative of a collaborative devil conspiracy. This is where Burroughs enters the scene.

Burroughs: the Devil in human form?

In the first half of 1692, numerous Salem villagers were accused of inflicting maleficium around the colony under Satan’s instructions, with the typical suspect usually being the elderly female widow. Yet, when Burroughs was accused of witchcraft in May of that year, he was not just suspected of inflicting maleficium on a malicious leader’s behalf, but the one ordering the maleficium. He was accused of being Satan himself, or rather, his anthropomorphic version that had vowed to destroy New England step-by-step. This assumption, of course, stemmed from the population’s paranoia about an evil cult aiming to destroy the colony’s European foundations, which was certified by Tituba’s confession some months earlier. In his case, therefore, his academic and religious education worked against him, as it reaffirmed both his extensive knowledge on the kingdom of hell, but also his ability to use rhetoric to persuade/intimidate villagers to join his malicious group. This is also the case for his gender. Under a Puritan-patriarchal order, the assumption that a woman can lead Satan’s sabbath is arbitrary to say the least – female nature is seen as too gullible and naïve to show leadership abilities. On the contrary, a young, educated man who can combine knowledge, charm, and power to recruit members, can easily be seen as its ultimate mastermind. But this is not the only reason Burroughs’ persecution is significant.

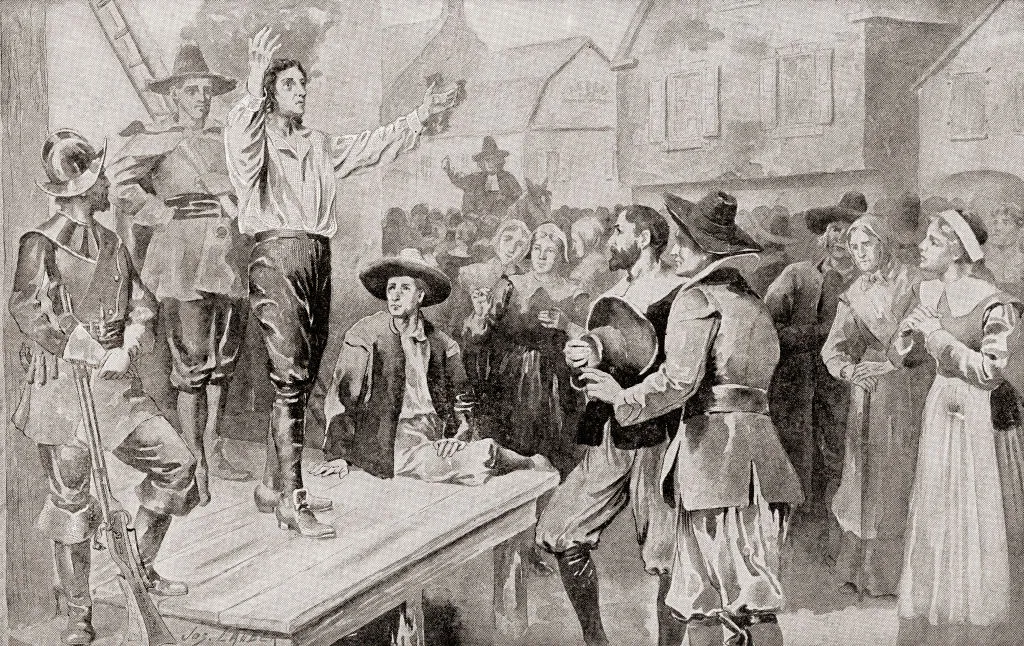

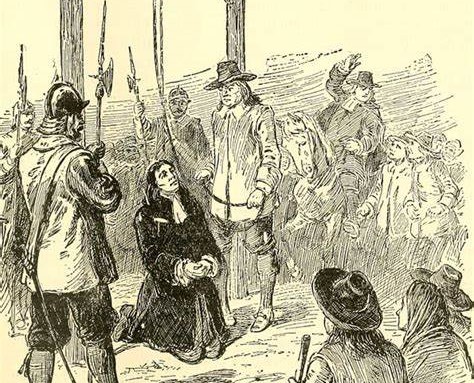

Burroughs was found guilty based predominantly on testimonies from fellow residents of Salem, and was executed despite overwhelming empirical evidence that he could not have been a witch. The arbitrary persecution of a member of the status quo hence made the rule of law flexible in the eyes of Salem community, sparking, for the first time, accusations against its sociopolitical elite. In particular, in her deposition against him in August 1692, Ann Putnam testified that he tortured her when she asked him to stop tempting people to give their souls to the devil, whilst Richard Carrier claims to have seen him at the witches’ meeting (sabbath) to administer sacrament. These and other depositions, pointing to his “supernatural” physical strength, paint a picture of Burroughs as a malicious witch leader determined to destroy Salem if he is not stopped. Yet his physical examination on August 4 shows no witch marks that would indicate his membership in the Devil’s conspiracy. What’s more, he recited the Lord’ s Prayer prior to his execution, which Salem’ s judiciary had deemed impossible for anyone engaging in Satan’s witchcraft. His execution thus signified a turning point in the perception of “justice” in Salem; verdicts were ultimately more about accusations than empirical truth, as the judiciary appeared to ignore its own theological statements. This perception of a “blurry” rule of law, in combination with the realisation that even the elite can be punished, ultimately started a chain reaction of accusations against the Salem elite by the Village community. This expanded beyond Salem, with witch accusations reaching the wife of the Governor of Massachusetts, which pushed him to end the Salem Witch Trials in May 1693. Burroughs’ elite status and execution were arguably the beginning of the end.

References

- Levack, B. The Witchcraft Sourcebook, second edition. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Salem Witch Trials: Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. Available here

- Baker, Emerson W. A Storm of Witchcraft : The Salem Trials and the American Experience. Cary: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2014.

- Hill, Francis. A Delusion of Satan: The Full Story Of The Salem Witch Trials. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2002.

- Newman, Janice Lee. “Reverend George Burroughs: The Ultimate Scapegoat.” PhD diss., University of California, 1997.