By Katya Mavrelli,

What is wrong with the Turkish economy? Why is the Turkish lira plummeting continuously? Is there a “reverse” button available somewhere?

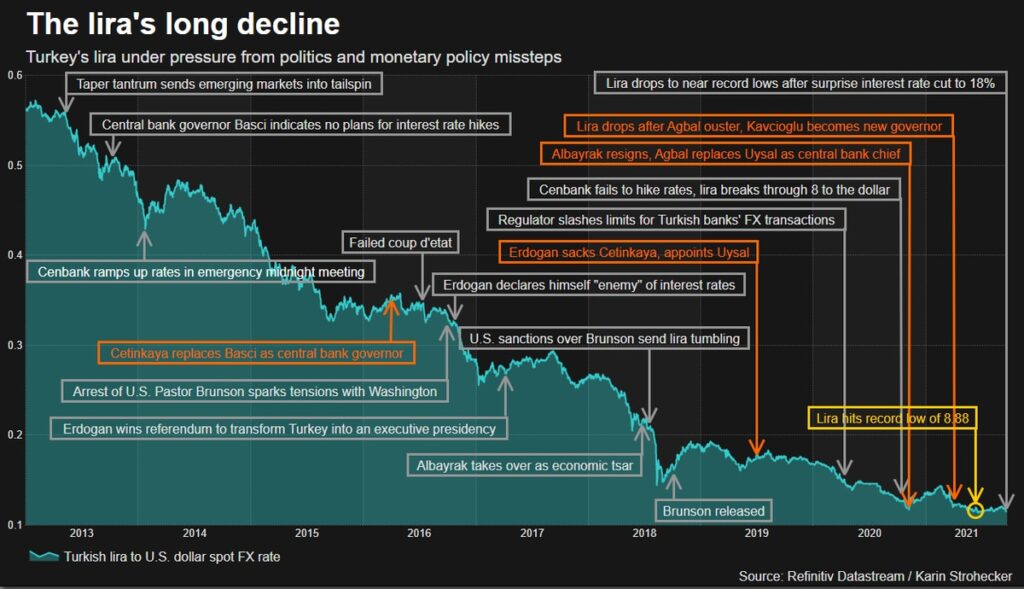

The story of Turkish economic decline is one that has dominated the headlines for years, if not decades. Chronic inflation, sudden economic growth, foreign investments, dependence on imports, more inflation – there is no clear pattern. The controversial trajectory that the Turkish government is following and that Turkish economic experts are implementing to interpret the ongoing crisis tells a tale of emergency. However, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan seems to be confident in his ability to swoop in and save the state from impending economic default.

So, what are Erdoğanomics?

A term coined to refer to the sudden –and quite impressive– economic maneuverings that Erdoğan has embarked on, since the significant deterioration of the Turkish economic crisis. His logic? Lower interest rates will reduce inflation and increase capital flows. The “new economic model” has the potential to raise investment, employment, and exports and enhance Turkey’s independence from other countries.

However, this economic experiment in the face of inflation has led to the collapse of the Turkish lira, soaring prices that are unsustainable for the vast majority of the Turkish population, and the rising cost of inputs for firms.

As suggested by standard economic theory, increasing base interest rates means the cost of borrowing for commercial banks increases, which raises their own interest rates. Savings, thus, give higher returns and borrowing becomes expensive, which lowers spending in an economy and slows down economic growth. More cash is being held in bank accounts and less is being spent, which in turn suggests that the money supply becomes tighter and demand for goods and services drops.

However, Erdoğan’s economic thinking has been often criticized – not by political commentators and political analysts, but by the economic community itself. The IMF’s Olivier Blanchard et al. suggested that higher interest rates may actually lead to higher inflation. The directing of large capital inflows into an emerging economy, such as the Turkish economy, may often lead to credit booms and rising output, and more inflation.

According to their theory and under the open-economy macroeconomic model, capital inflows are contractionary, because they lead to currency appreciation and net export reduction. However, when it comes to the economic policy followed by emerging markets, capital inflows are thought to lead to credit booms and rising output.

However, Erdoğan’s economic policy is following a different course. It has been running persistent deficits on its current account, with imports often exceeding exports, and experiencing systematically high inflation. The annual inflation rate has been above 10% for five years in a row now, which points to an unaddressed price growth problem dominating the Turkish economic scene.

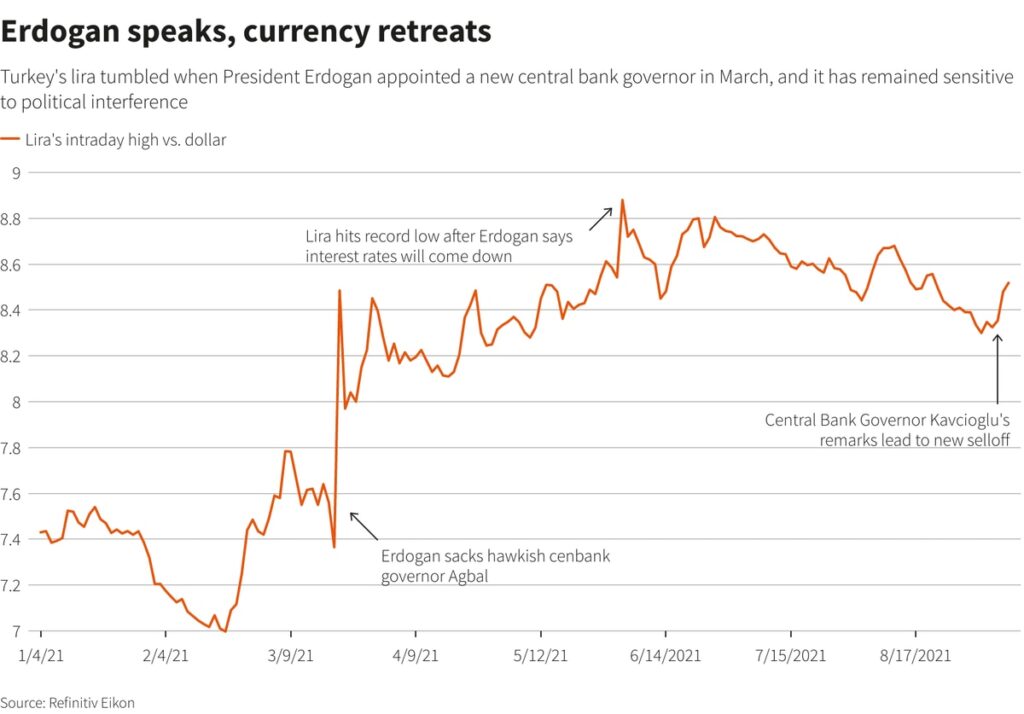

Even if, initially, higher interest rates were attractive for capital inflows, this increased spending and inflation within Turkey, what Ankara should have done in the first place would have been to implement a tighter monetary and fiscal policy, accept growth deceleration, and plan for more ambitious economic openings once the economy regains its strength. However, Erdoğan’s own economic calculations encouraged him to handpick the Turkish central bank governor time and again, and embark on a series of expansionary moves.

By initially lowering the value of the Turkish lira, he thought, and encouraging exports by boosting smaller manufacturers, he would also successfully shift spending to domestic goods and services and give some breathing space to the internal Turkish market. While the thinking could have been justified, potentially, due to the emphasis on the health of the domestic economy and the shifting of weight towards more internal competition, this plan quickly backfired.

The trade deficit that has been run for years is still unaddressed, and Turkey has grown more reliant on foreign investments, loans, and foreign currencies. People’s purchasing power, as shown by the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) metric, has been significantly reduced and savings in lira have become close to worthless.

Economists often use Turkey as the classic example of the “middle-income trap”. Essentially, this is the difficulty that countries experience when they emerge from poverty, and they become members of the rich-counties club. Martin Raiser, a former Turkey director for the World Bank, has described this as “the need for a shift from a know-who to a know-how approach”. It needs to develop resilient institutions that can withstand political regime change and support growth both in the short and long-term.

Where is Erdoğan going with this?

The Turkish economic model that we are currently seeing tells a tale of impending doom, of necessity for intervention, and call for salvation. However, the problem does not lie in the fact that the Turkish government is not able to introduce such solutions. It is not empowered to actually pivot away from the Erdoğanomics model.

Erdoğan has become personally and directly involved in the progression of Turkish economics. His direct appointment of central bank governors and finance ministers shows a direct involvement that should not characterize economic developments. When the lines dividing the realms of politics and economics become blurred, then their intertwining will make it harder for the government to implement sound, pragmatic, and independent decisions. It also reduces credibility in the government by domestic and foreign factors – something that can shatter economic or make economic systems rise from the ashes. While this presidency embraces the idea of a strong and stable currency, it seems to have left the importance of a strong central bank out of the equation.

What Turkey needs is a redefining of economic thought and policy – easier said than done, however. It is one thing to say that economic approaches need to be redefined and economic decisions need to be rethought, and another thing to indeed observe shifts in Turkish economic policies.

Turkish industry and manufacturing are the lifelines of the Turkish economy: they provide the pillars upon which the entire economic model, however ambitious, is based. This is why the maintenance of its competitive advantage has to be located at the top of any Turkish government’s economy. Education and training will allow the existing sectors to become more competitive and to ensure they can keep sustaining the Turkish economic model for the next years.

Attracting investments and seeking salvation from external agents should become a model of the past. No matter the political significance of these economic alliances, as seen with the friendship with Qatar that has turned into a model of economic sustenance, the Turkish economy should try to stand on its own feet and not rely on external supporters. This will increase its independence and not make its economic health reliant on the health of other economies.

Measures to manipulate interest rates may work, but only in the short term. The proper, cohesive, and competitive management of the economy will pave the way for the establishment of a healthy, competitive, and holistic economic system. Naturally, these are things that take time –but laying the foundations now will allow growth in the future– sooner rather than later, and before it is too late for any economic maneuverings.

References

- Turkey flies in the face of economic orthodoxy, arabnews.com, Available here

- How Turkey can overcome its economic challenges, arabnews.com, Available here

- Erdoganomics, economist.com, Available here

- What’s wrong with Turkey’s economy? ‘Erdoganomics’, washingtonpost.com, Available here