By Vera Rodriguez,

The AI Summit in Paris this past February sent a clear signal: global powers are accelerating toward a new frontier of technological competition, where leadership in artificial intelligence is closely tied to control over strategic infrastructure. From disinformation campaigns to cyberattacks on critical infrastructure, technology has emerged as a potent geopolitical tool. The battlefield is no longer solely territorial; it is also virtual. And the weapons? Hackers, bots, data.

As the geopolitical significance of technology increases, so does the recognition of its strategic value. Just as fossil fuels have long been pillars of national economies and citizens’ welfare, digital infrastructure is becoming equally essential.

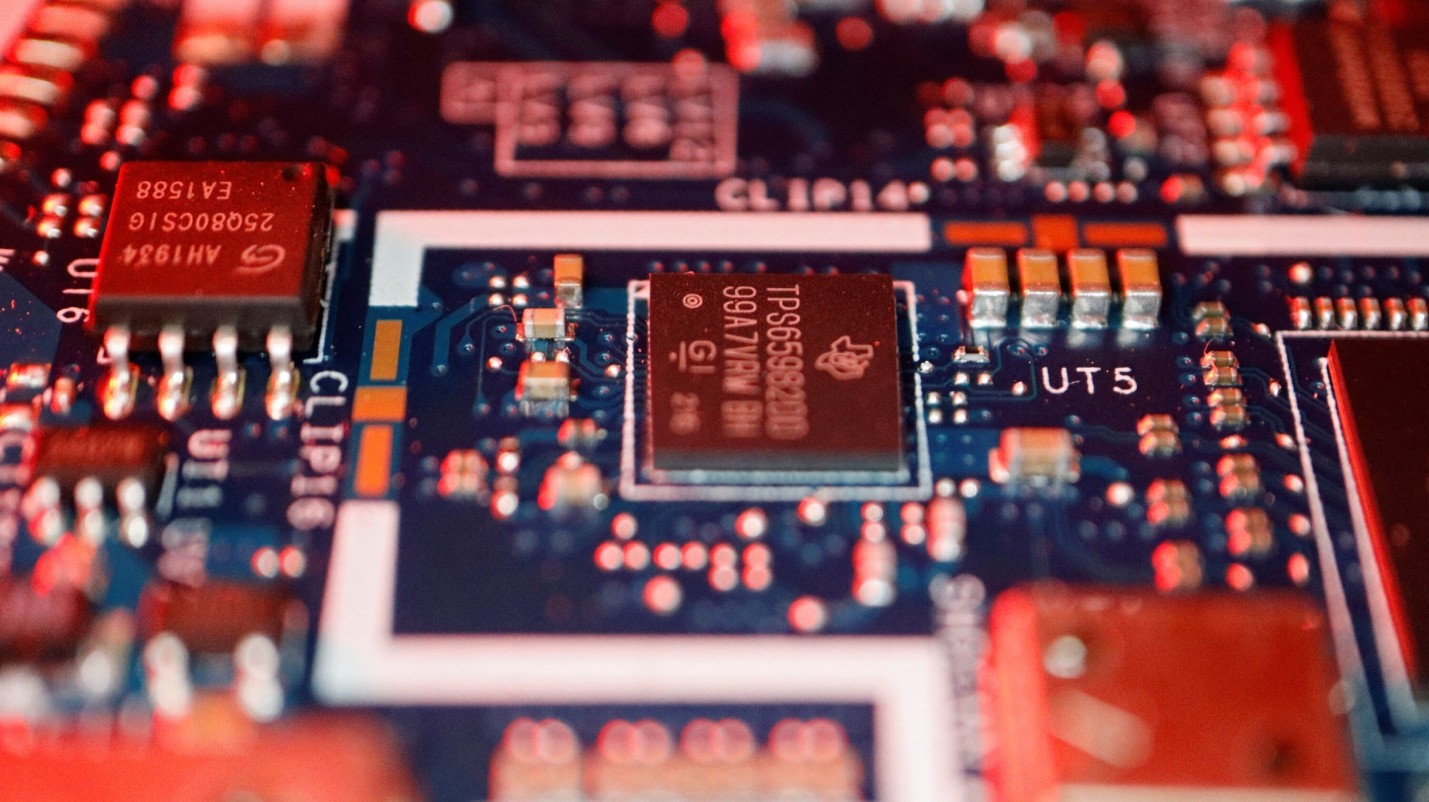

At the heart of this race lies the semiconductor industry—an essential yet highly fragmented global supply chain. Semiconductors, or integrated circuits (ICS), commonly referred to as chips, are small devices that control the flow of electrical signals in electronic systems. They constitute the most manufactured devices in human history, and are small slices of silicon containing microscopically small, interlinked switches—called transistors. Overall, the more transistors a small slice of silicon can have, the more advanced the chip will be. Therefore, advanced chip production relies on fitting as many transistors as possible onto a single chip.

Today, the largest chips contain more than 50 billion transistors. The smallest structures in chips, such as those measuring 5 nanometers (nm), are crucial for data centers, 5G smartphones, edge computing, and machine learning or AI. Researchers are currently investigating the production of 3 nm and 2nm chips, as well as the development of quantum computers. However, most chips needed for the global economy are not highly advanced, as major market segments—such as the automotive, healthcare, defense, and manufacturing industries—do not require state-of-the-art or ultra-small chips. Although not cutting-edge, the provision of semiconductors remains crucial for these industries.

The process of semiconductor production is highly globalized. No country is entirely self-sufficient in semiconductor manufacturing, and this is expected to remain the case due to the complexity, geographic specializations, and deep interdependencies across the value chain. The system relies on approximately 300 inputs, including ultra-pure silicon wafers, gases, and chemicals, as well as more than 50 classes of high-tech manufacturing equipment. Until now, Western countries have retained the high-profit-margin segments of the chip supply chain while relocating other, less profitable (but equally important) processes to Asian countries. This has resulted in highly decentralized chip production, especially in the case of the most advanced semiconductors.

However global this process may be, a trend toward a polarized geopolitical environment is now threatening the international nature of the chip value chain. In 2025, global powers such as the United States and China are seeking to leverage their chip technologies through new initiatives aimed at boosting their competitiveness in developing cutting-edge technologies. For both Beijing and Washington, the side with access to advanced chips will gain a significant advantage in technological development. For other mid-sized countries, this competition increasingly resembles a situation of having to ”choose sides.”

A prime example of this growing bipolarity in the advanced tech trade—driven by the U.S.-China rivalry—is the ongoing trade war between the two powers. China’s global presence has been on the rise in the last quarter of the decade. Today, many more countries trade more with Beijing than with Washington. Furthermore, the launch of the “Made in China 2025” strategy—a blueprint designed to transform China’s economy from the world’s top manufacturer of low-cost goods into a leader in high-tech and innovative manufacturing—has further fueled this dynamic.

References

- Strengthening EU chip capabilities: How will the chips act reinforce Europe’s semiconductor sector by 2030? The European Parliament. Available here

- Strengthening the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain In An Uncertain Era. BCG and Sia. Available here

- Towards a more competitive semiconductor industry for Europe. ESIA. Available here

- What is a semiconductor? An electrical engineer explains how these critical electronic components work and how they are made. The Conversation. Available here

- Semiconductor design and manufacturing: Achieving leading-edge capabilities. McKinsey & Company. Available here

- Dutch semiconductor interests in Asia. Leiden Asia Center. Available here

- Sommet pour l’action sur l’intelligence artificielle. Élysée. Available here