By Eirini Tassi,

From the moment one steps foot in Edinburgh, they are immediately exposed to intriguing dualities: the fusion of contemporary with old buildings, the interaction of dark brown shades with the vivid red and blue, as well as the grey cloudiness with the soft sunbeams emerging from behind Edinburgh Castle. Even the city’s architecture appears to be marrying the pointy gothic tympana with the doric-order columns. Yet, I would argue that one particular structure stands out: the National Portrait Gallery.

Hosting the largest portrait collection globally with over 215 thousand artworks, this building, which is also undoubtedly an art piece in itself, sits vividly, and proudly on Queen Street of downtown Edinburgh. And of course it does- how could a red-sandstone neoGothic structure ever stand quietly in any city? Its brilliant Victorian-era architect Sir Robert Rowand Anderson knew exactly what he was doing when he merged this structure within Edinburgh’s Georgian neoclassical configuration back in 1885. Not only do the stained-glass windows and their pointed arch frames give passers-by a glimpse of the cultural treasures hiding behind them, but in combination with the earthly red hue the building is constructed with, they convey to individuals a certain warm and unusual sense of intimacy; one pushing them to delve deep into the artistic plurality it hosts on the inside. As unreal as the building is on the outside, it is even more so on its interior.

The Great Hall, the nucleus of the Gallery, is built and decorated with nuanced artistic and architectural detail, yet without being overwhelming or too multifaceted for its audiences. It is surrounded by a Processional Frieze: a decorative artwork unraveling in all four sides of the Hall, painted by William Fergusson Beasley Hole in 1897. This offers an encapsulation of important Scottish history, by portraying 155 significant national figures behind one another, from kings like James II to ancient fighters like Calgacus, and from the 19th century, to prehistoric humanity. From a first glance, the religious artistic influences of the work are more than clear; the figures all emerge from a gold backdrop, many being dominated by Byzantine-like hues in their depiction.

And yet the detail does not stop there: Ferguson gives them expressive, serious facial characteristics, which in combination with their straight and relatively forward-leaning posture indicates that they gaze proudly towards the past; they observe their forefathers with the upmost respect, for providing them with the concrete foundations to lead, invent, and influence in their own generations (Louis 2021). That way, it even likens a grand Scottish family tree; not one fused together merely by mostly common ancestral blood, but one uniting actors whose profound ideas, rhetorics, and actions shaped the course of history. All these individuals culminate to Caledonia, the anthropomorphic personification of Scotland, and one of few figures that looks completely forward in her depiction. Despite her sharp, intimidating stare, which follows the viewer throughout the Hall, Caledonia appears as an indestructible warrior; a general prideful of the humankind that surrounds her, but also one prepared to guard it with her whole divinity.

Similarly to the earthly composition of the building itself, the natural marries the human element, with Caledonia subtly revealing the starry night sky from the curtain behind her. This leads to an impressive visual of the constellations of the Northern Hemisphere in the Hall’s ceiling, one which ultimately reminds the audience that the colossal divinity of nature is an integral aspect not merely of Scottish history, but of humanity itself. Natural sunbeams entering the Hall through its stained-glass windows are austere; the light is not too little to hide these impressive visual dualities behind the darkness, but it is also not too bright in a way that overwhelms those who seek to unravel them.

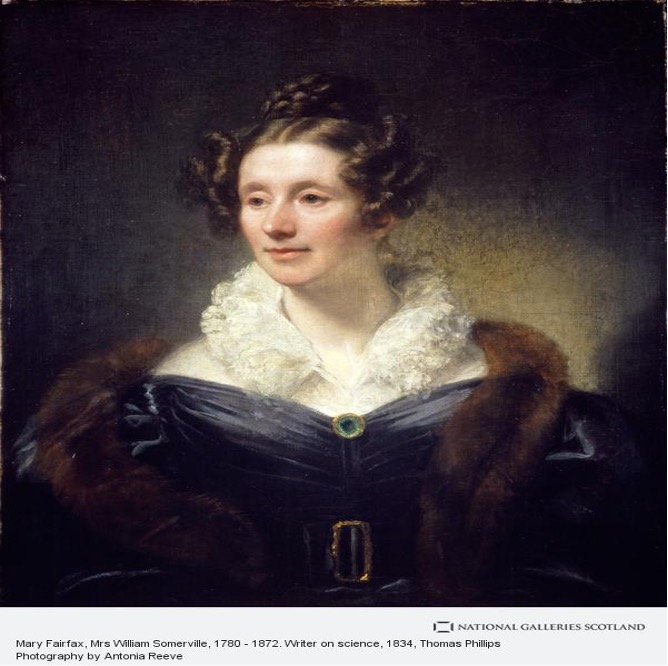

Moving finally to the portrait exhibitions themselves, throughout the multiple photography, painting, and paper artworks, what undeniably stands out is the display collection of Victorian heroes and heroines. These are not mere formal depictions of important Scottish figures, but are rather produced with the “Great Man” ideology in mind; an influential view of history back in the 19th century, in which individuals are integral in creating and advancing history. The portraits combine this narrative with the strong male and female presence that shaped the Victorian period to produce heroic, triumphed depictions of individuals. Mary Somerville for instance, was systemically barred from accessing formal education due to being a woman, yet became a self-taught scientist with significant contributions to mathematics. In her portrait by Thomas Phillips, she poses with a strong and prideful posture, gazing rightwards with a sharp stare. The artist juxtaposes the dark brown and blue hues of her clothes and background, with the vivid ones surrounding her face. This is done in no coincidence, but rather, to signal to viewers the artwork’s heroic anthropocentric focus: that Somerville, as a heroine, is shaping the course of Scottish scientific history. Other artworks possess similar characteristics, from Scott-Moncrieff pridefully posing similarly to an Ancient warrior, to leading Art-Nouveau architect Charles Mackintosh standing confidently and holding his designs. The audience comes face-to-face with such pioneering historical figures, not merely seeing them from afar or from below as with the Hall’s frieze, but this time being able to intimately stand on their same level; two humans across vastly different centuries.

The National Portrait Gallery of Scotland was, is, and will continue being a structure that stands out. A loud structure; one that intimidates, yet welcomes passers-by to explore the rich human history it displays. In conflicts, in pandemics and in rapidly changing political landscapes, this art hub remains an intact time-capsule of Scotland, and to an extent, to the course of humanity in itself.

References

-

“Francis Henry Newberry”. nationalgalleries.org. Available here

-

“Edward Stanely Mercer”. nationalgalleries.org. Available here

-

“Thomas Phillips”. nationalgalleries.org. Available here

-

“Heroes and Heroines | Idealism and Achievement in the Victorian Age”. nationalgalleries.org. Available here

-

“Scottish National Portrait Gallery”. nationalgalleries.org. Available here

- “William Brassey Hole”. nationalgalleries.org. Available here