By Konstantina Kerpinioti,

History is extremely important for every nation, due to the fact that it is an integral part of its culture. Apart from that, knowing your country’s history helps you to avoid making the same mistakes your ancestors made and to achieve better results in the future. For all these reasons I decided to dedicate this article to a landmark day in Greek history: the Pontic Greeks genocide.

But let us take things from the very beginning. Pontians constituted a large percentage of Hellenism that inhabited the north Asia Minor and particularly in the region of Pontus, after the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire. The fall of Trebizond in 1461 by the Ottomans did not make them lose their national consciousness. Even though Pontians were a minority (covering only 40% of the total population), they managed in a short period of time to settle in the urban centers and dominate the economical life of the region.

It is noteworthy that the financial development was accompanied by demographic growth and spiritual evolution. In 1865, the Greeks of Pontus amounted to 265,000, in 1880 to 330,000, and at the beginning of the 20th century, they reached 700,000. In 1860, there were 100 schools in Pontus, whereas in 1919 they estimated at 1,401. Apart from schools, Pontians had plenty of printing presses, magazines, newspapers, clubs, and theatres which showed that their intellectual level was pretty high.

As far as genocide is concerned, it is divided into two phases: It began after the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 by the Young Turks, intensified during the World War I, and culminated much more brutally and inhumanly — in the period 1919-1923, under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, when in May 1919 he landed in Kerasunda (today Giresun).

1908 was a significant year for people who lived in the Ottoman Empire. It was the period in which the Young Turks’ movement marginalized the Sultan, manifested, and prevailed. Many people hoped that the Young Turks’ movement would improve the state of the empire and their living conditions at the same time.

Soon, however, it was proved that the Young Turks did not have such purposes. On the contrary, they devised a plan to persecute the Christian populations by taking advantage of the involvement of European states in World War I. Greeks had already dealt with another case (the “Cretan Issue”), therefore, they could not open another front with Turkey.

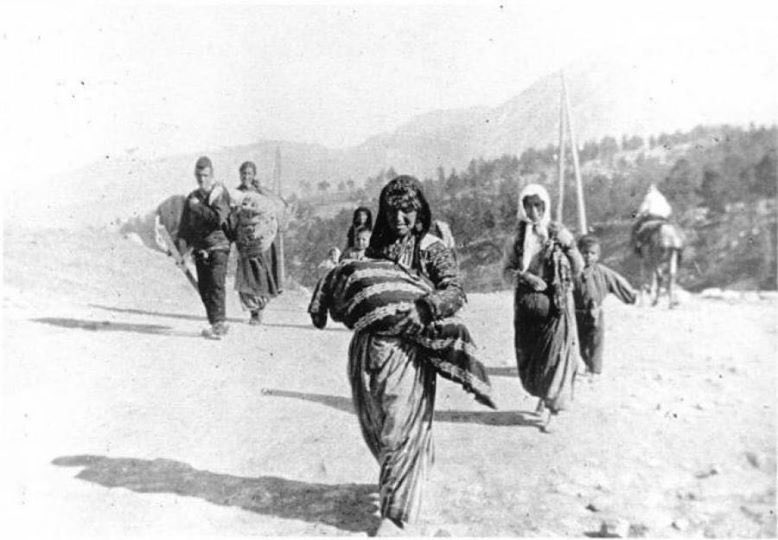

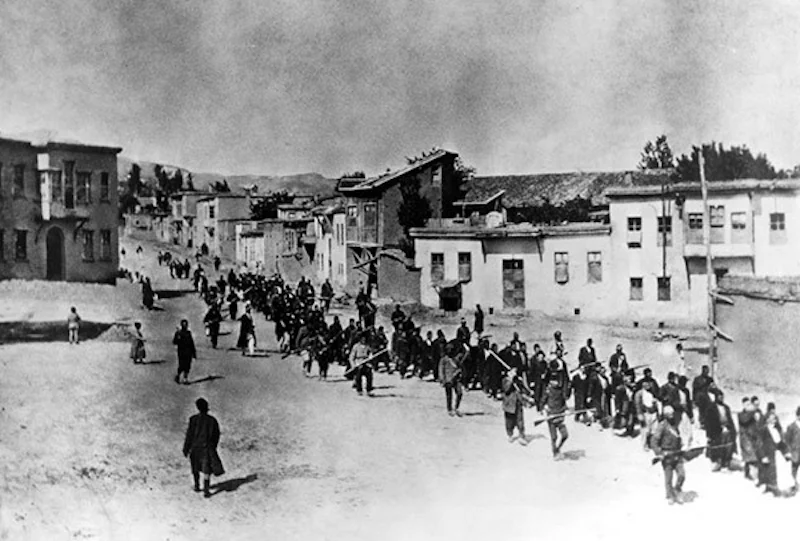

The Turks, under the pretext of “state security”, forced a large part of the Greek population to move into the inhospitable Asia Minor hinterland through the so-called “Labor Battalions” (Amele Taburu). Men who did not join the army were forced to serve in the Labor Battalions. They worked in quarries, mines, and road buildings, under exhausting conditions. Most died of hunger, hardship, and disease.

Like Americans, Greeks went up to the mountains as rebels in order to salvage what is possible, as a reaction to the oppression of the Turks, the murders, the exiles, and the burning of their villages. After the American genocide in 1915, the Turkish nationalists under Kemal Atatürk had many opportunities to exterminate the Greeks.

In 1919, the Greeks, together with the Armenians and having been supported temporarily by Venizelos’s government, made a lot of efforts to create an autonomous Greek-Armenian state. This plan was thwarted by the Turks, who took advantage of the fact to proceed with the “final solution”.

On May 19, 1919, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk landed in Samsun (historically known as Sampsounda) to begin the second and more brutal phase of the Pontian Genocide, under the guidance of his German and Soviet advisors. By the Asia Minor Catastrophe in 1922, the number of Greek- Pontians who died exceeded 200,000 while some historians put the number at 350,000.

The majority of the Pontian refugees that came to Greece at that time settled in the regions of Macedonia and Thrace, while many fled to the former Soviet Union. In 1923, within the framework of the Treaty of Lausanne, an exchange of populations took place between Greece and Turkey, which included the Christian (Greek-speaking or not) inhabitants of Pontus and those of the rest of Asia Minor. However, part of the Pontian population, who had previously covered Islam — including the so-called “Crypto-Christians” were excluded from the exchange and remained in their homelands as Turks.

After an admittedly considerable delay, the Greek Parliament voted unanimously on February 24, 1994, to proclaim May 19 as the Day of Remembrance for the Genocide of the Pontic Greeks. Since then, the worldwide campaign of Pontian organizations for the international recognition of the Genocide of the Greeks of Pontus has been launched. Today, the crime of Pontic genocide is recognized by Cyprus (1991), Sweden (2010), Armenia (2015), the Netherlands (2015), and some of the states of the USA: New York, New Jersey, Columbia (2002), South Carolina, Georgia, Pennsylvania (2003), Florida, Cleverland (2005), Rhode Island (2008), Indiana (2014), South Dakota (2015), and West Virginia (2016). The states of South Australia (2009), Toronto, Canada’s largest city by population, the capital of the province of Ontario (2015), and other cities in the country.

Despite the extremely difficult conditions Greeks went through in this era, they managed to survive, not lose their national spirit, and maintain Greek tradition, something that makes me proud of my country and the people who lived in even more.

References

- Γενοκτονία Ποντίων: Δικαίωση ζητούν τα 353.000 θύματα, protothema.gr, Available here

- Η Γενοκτονία των Ποντίων, sansimera.gr, Available here