By Katya Mavrelli,

Over the past few years, countries have developed new ways to conduct their foreign policy. Drone technology has significantly improved, providing an advantage to countries that could not even begin to think about the potential of their foreign policy initiatives. Even though all variables in their equation of political stability may not be perfectly stable, drones have provided them with an additional advantage. Turkey constitutes the most notable example of a country that has gained a significant competitive advantage from the use of drones. How are drones reshaping the setting of Turkish foreign policy? And what are the implications on regional geopolitics?

Turkish drones are now a common sight in many places in the greater Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are now at the forefront of Turkish military initiatives, applying a central role in the development of several regional conflicts and military initiatives. From the Syrian civil war to the Tigray conflict in Ethiopia, Turkish drones are adding an additional advantage to the national intelligence of several countries – and Turkey is also benefitting from this process.

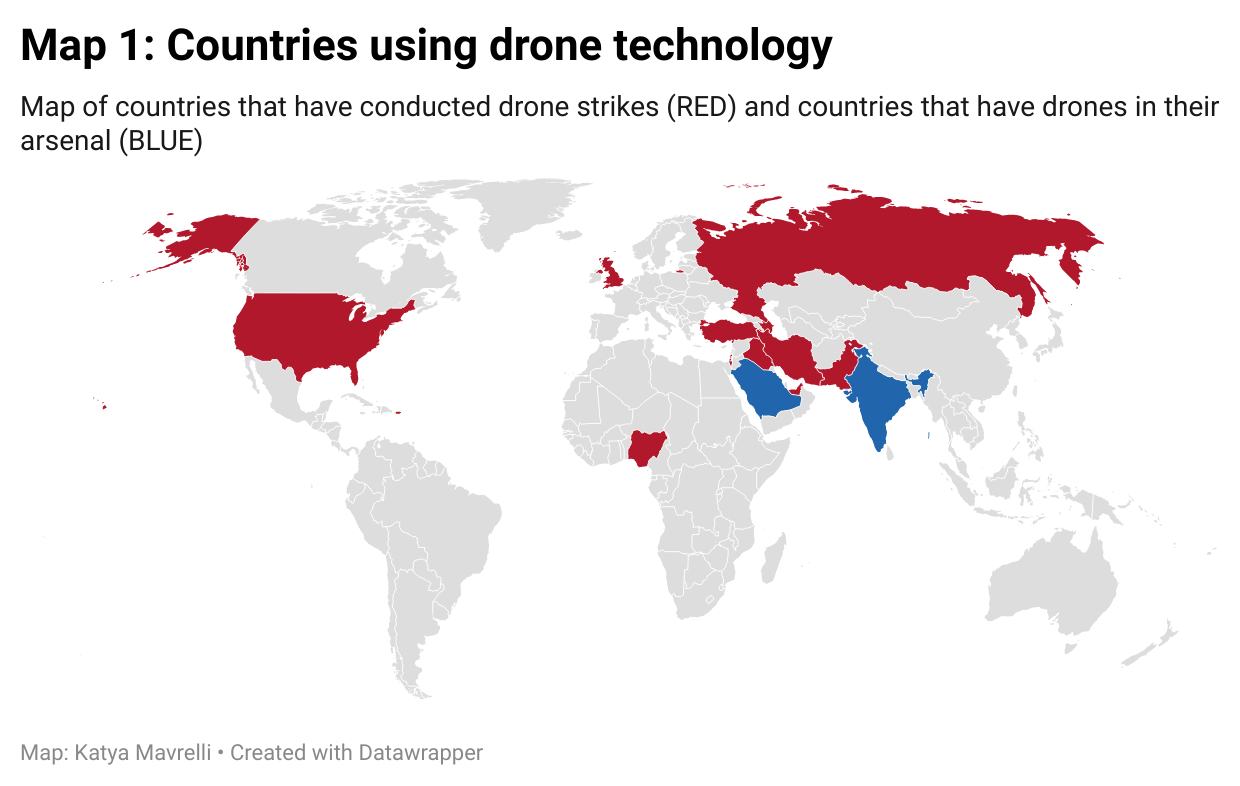

The most notable drones that helped Turkey enter the market and gain an advantage in this field are the Bayraktar TB2 tactical UAVs, produced by Baykar Makina, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s son-in-law Selçuk Bayraktar’s company, and Anka-S, a medium altitude long endurance (MALE) class platform that is produced by the Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI). These technologies are produced in Turkey, which significantly strengthens the Turkish military sector. The strong – and increasingly stronger – sector is a juxtaposition to the weak economy, which is still worsening the living standards for a big proportion of the Turkish population. Turkey stands out among all countries that possess drone technology as the country that has developed UAVs in a faster and more efficient way and as a country that deploys them most frequently and for all purposes.

Turkey’s use of drones did not start out of a sudden, as a need to catch up with the latest military trends or as an internal need to flex military muscles. It has been a process developing progressively over the past decades. It first turned its attention to the UAV business in 1996, purchasing 6 unarmed drones from the US. The first drones, the GNAT 750s, were simple aircraft that did not possess the advanced features today’s drones do – all they could do was assist in surveillance activities and collect information. They were used widely in the southeast part of Turkey, where drones provided footage of PKK movements. In 2006, Turkey continued its quest into turning the drone business into a more efficient one by ordering 10 unarmed Heron drones from Israel. Even though the drones took a long time to be delivered, their technology was efficient and served some purposes partially.

After Ankara and Jerusalem severed their diplomatic ties in 2010, the former announced that it would further improve its drone technologies by replacing the Herons with a domestically-produced model, the Anka – or Phoenix –, which was also unarmed. Even though the drones were serving their purposes, they did not possess the “kill chain” technology, as Necdet Özçelik, a former officer in the Turkish Special Forces Command mentioned. However, even though the drones did not possess this technology, they honed Turkey’s military strength and allowed it to become a rising competitor against well-established players in the drone field. By 2016, Turkey had successfully pivoted away from reliance on the US, Israel, and other drone-technology exporters and set on the path to further develop its arsenal.

The widespread use of these such technology initiates a new drone age for Turkey, one that puts it among other big powers that have firmly established themselves in the business for decades. The switch to domestic production of drones provides Turkey with an additional advantage – the strengthening of the internal market and the fortification of the national production capabilities ensure that in the near future, the payoffs from this sector will benefit the entirety of the country. Turkey is a rising drone power also because of the diplomatic advantage this technology has brought. Exporting the TB2 drones across Europe, to countries like Albania, Poland, and most recently Ukraine, Central and South Asia, Africa, and the Gulf has opened more diplomatic doors to Turkey since the deals have involved key strategic partners or regions of interest.

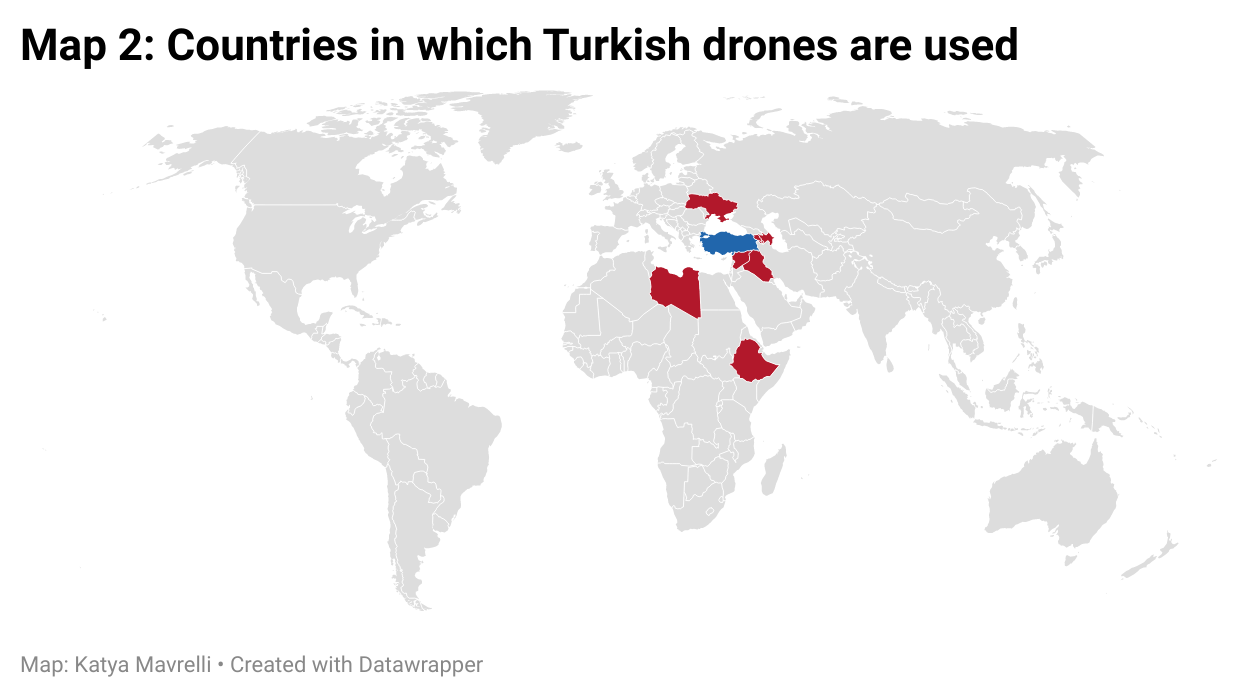

Turkish drones have tipped the balance in several conflicts, from Libya in 2020, to Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine. In Syria, Turkish drones allowed the Syrian opposition forces to stop a government offensive in Idlib that would have pushed them back to Turkey. In Ethiopia, drones enabled Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali to push back Tigrayan rebels and prevent a complete national takeover. In Nagorno-Karabakh, the drones gave Azerbaijani forces an additional advantage against their Armenian counterparts. And in Libya, they were the means of support for the internationally recognized government in Tripoli, which facilitated the toppling of the rebelling General Khalifa Haftar.

Even though this drone technology has provided additional agility for Turkish forces, enabling them to be more efficient and to finetune their intelligence and security capabilities, it brings more challenges with it. The drive technology has been used as part of an intervention strategy in regional conflicts which has disrupted several bilateral ties. Upsetting old rivals, like France, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates means that while Turkey gains in strategic and diplomatic terms from some relations, it loses in others. A notable example was in March 2020, when Turkish drones were decisively intervening in the Libyan civil war, Egypt, Cyprus, France, Greece, and the United Arab Emirates formed an alliance in order to halt the Turkish activities in the Eastern Mediterranean and to uphold the maritime and geopolitical equilibrium.

Turkish diplomacy has been deployed in the riskiest manner in Ukraine. The purchase of Turkish drones dates back to 2019 when Kyiv first purchased them to deploy them against Russian-backed separatists in the Donbas region. Given the current conflict, the employment of these drones has become more purposeful. There have been more than 60 successful strikes against Russian tanks, artillery pieces, vehicles, and even supply trains with the help of TB2 drones. This means that the hold Turkish drones have over Russian forces strengthens Turkey’s relationship with the West – as this is something that can turn the tables to the conflict in Ukraine, Turkey is seen as the country that can tip the balance. Standing with Europe and backing the same side of the conflict means that Turkey is seen more favorably by the West, which is also shown by Turkey’s elevated NATO standing.

The conflict in Ukraine, however, means that Turkey has to pay attention to both sides. On the one hand, a Ukrainian victory means that its military technology will have been efficient enough to change the standing of a war, ensure European security and become an active protector of the current status quo. On the other hand, Russia’s victory will imply that Turkey’s economic and trade ties with Putin’s Russia will continue to grow. His intention to mediate the resolution of the conflict and serve as a third party towards a diplomatic solution means that Erdoğan tried to appease both sides and ensure Turkey’s future in either scenario. By doing so, he also aims to attract Russian oligarchs to Turkey, turning the country into a safe spot for them and their capital, which can strengthen the Turkish economy.

The use of these drones has the potential to align Turkey with the west once more after a period of turbulent relations. Despite the similar political stances, priorities, and diplomatic responses, western leaders are still concerned about Turkey given the unstable economic environment and the unsure political feature of the current government. With the June 2023 elections approaching, Erdoğan has to make sure that he leaves a dent in the Turkish national scene that is big enough for it to determine the future of all foreign relations. And even if the Turkish drone technology serves as an overall advantage, the biggest determining factor of the political course of the country remains the state of the economy.

References

- Remotely Piloted Ambitions: Drones in Turkish Foreign Policy, ispionline.it, Available here

- Turkey’s Lethal Weapon, foreignaffairs.com, Available here

- The dronefather, economist.com, Available here

- The second Drone Age, theintercept.com, Available here

- Turkey’s modern way of doing foreign policy: drone diplomacy, aspeniaonline.it, Available here