By Katya Mavrelli,

The domination of the political sphere by Russia and the normalization in Israeli relations with its Arab neighbors bring into mind images of a period of democratic resurgence in the Middle East. In an effort to redraw the political map of the region, nations scrambled for small pieces of the large pie of democracy. But a decade later, the Middle East is back where its started, taking leaps in the opposite direction and forgetting all about the massive revolutionary waves that led to the collapse of the status quo back then.

A decade ago this month, a young Mohammed Bouazizi set himself alight in Tunisia, as a sign of protest against local police officers who had seized his cart and produce. Almost a month later, the whole Maghreb was set alight with the explosiveness of revolutionary waves. And 10 years later, we are back to where we started, with the rise of authoritarianism and the dissolution of the helpless democracies that had started blossoming.

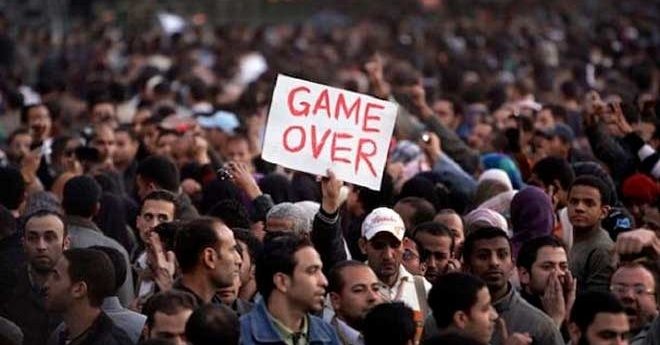

The lonely death of a street vendor quickly became the symbol of a holistic effort to redefine the political order, symbolizing the end of authoritarianism and the birth of democracy. Who would have thought that protests could so quickly turn into catalysts of regime change? Spreading from Tunisia to Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, Libya and Syria, the protests initiated the starkest period of civil unrest in the Arab world and turned into the region’s most profound transformation since the end of imperialism. Dictatorships were quickly exposed as vulnerable entities and the common stories of injustice, intolerance and undemocratic principles resonated from one corner of the Maghreb to the other.

Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution set the scene, leading to the ousting of the country’s president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Soon, similar protest movements threatened the survival of regional autocrats Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, Muammar el-Qaddafi in Libya and Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen. And while Bashar al-Assad managed to hold on to power in Syria, he did so at the cost of a brutal civil war that has caused the death of more than half a million people, has forced massive waves of refugees to flee the country, has internally resulted to the displacement of thousands of people and has brought foreign intervention into the Arab world once more, turning the scenery into an Iranian-Israeli battlefield. The movement, that soon came to be known as the Arab Spring, was a massive shock that unsettled decades of torpor and highlighted that feudal dynasties were no match for the power of a combustible street.

Uprisings were aided by the people’s ability to rapidly organize, highlighting the already existing dissatisfaction towards the regimes. The Arab world was the powder keg ready to explode, and the incident in Tunisia simply set it alight. By 2010, a series of events had made it significantly more challenging for the existing status quo to hold. Divides in living standards, an unaccountable elite and a rapidly growing youth with little access to opportunities led many to believe they had nothing to lose by protesting.

By mid-January, Tunisia’s Ben Ali fled to exile in Saudi Arabia and Egypt’s streets were about to explode into a revolution that toppled Mubarak, its autocrat of four decades. Libya was starting to teeter, and Syria’s Assad was struggling to maintain his family’s dynastic rule. In all four regimes, a series of institutions and constitutions masked the real origins of power: a family, a party, or an army. As these four pillars wobbled and came under threat, alarm bells started all the way to Iran and Saudi Arabia, which feared that the power of the people would signal an end to their regimes as well. The dominos continued to fall for years, with Algeria’s Hirak Movement erupting in February 2019, six days after Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced his candidacy for a fifth presidential term.

The protests of the Arab Spring are a pattern that exposes the political fragility of the affected states. With some leaders struggling to maintain their hold on power, and others successfully deploying their military apparatuses to remain unaffected, the weak legitimacy of pseudo-presidential republics left them vulnerable, exposed and unstable. The movement opened the way for the rise of the Islamic State, that managed to find a foothold in states were central governments had no control. And despite the dissolution of the “caliphate”, as long as the problem of state weakness goes on, the group will find affiliates across the Arab world.

The Arab Spring turned into a movement that sought hope and change in governance. The corrupt and old regimes were no longer fit to serve the needs of the rapidly changing population. And in the midst of this turmoil, political Islam managed to reserve a seat on the table. Representing the main alternative to secular autocracy over the last decade, it has become a largely successfully movement, winning elections wherever they took place. This was the case with Tunisia’s moderate Ennahda party, which made the Jasmine Revolution the only true success story, with all three elections since 2011 having led to peaceful transfers of power. On the contrary, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood managed to win the presidency in 2012, but after just one year, the military led by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi ousted Mohammed Morsi and installed a regime even more repressive than Mubarak’s.

No story of the Arab Spring can be completed without reference to the U.S. After Obama sacrificed America’s two closest regional allies by allowing the ousting of Mubarak and Ben Ali, he opened the way for a redrawing of the Middle East’s strategic map. Soon later he negotiated the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran as an effort to rebalance US foreign policy, which only opened the way for Russia to expand its influence in the region. And Putin wasn’t the only one to capitalize on the instability of the Arab world. Israel, Iran and Turkey were quick to mark this as an opportunity to extend their regional influence and build on their leaders’ aspirations.

The geopolitical terrain of the Arab world has been shifting since the formation of the nation-states in the post-colonial era. Leaders are toppled, parties’ emergence and policies shift in an attempt to either heighten or block the waves of rapid change. And as 2021 begins, it becomes evident that the goal of democracy has started mobilizing people once more.

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica, The Jasmine Revolution. Available here.

- Voice of America (VOA), Ten Years Later, Arab Spring Left Many with Unfulfilled Promises. Available here.

- International Bar Association (IBA), 10 Years after Arab Spring: Is Fighting Corruption a Reality or a Dream? Available here.

- The Guardian, Hosni Mubarak Resigns – and Egypt Celebrates a New Dawn. Available here.

- US National Public Radio (NPR), The Arab Spring: A Year Of Revolution. Available here.