By Athina Varvesioti,

“Tell us about yourself”, your new professor kindly asks you when you are asked to introduce yourself in class. “Tell us about your interests”, your interviewer asks when they’re about to employ a new individual. “Tell me about you”, a serial killer demands, before they hypnotize and manipulate you into committing a murder.

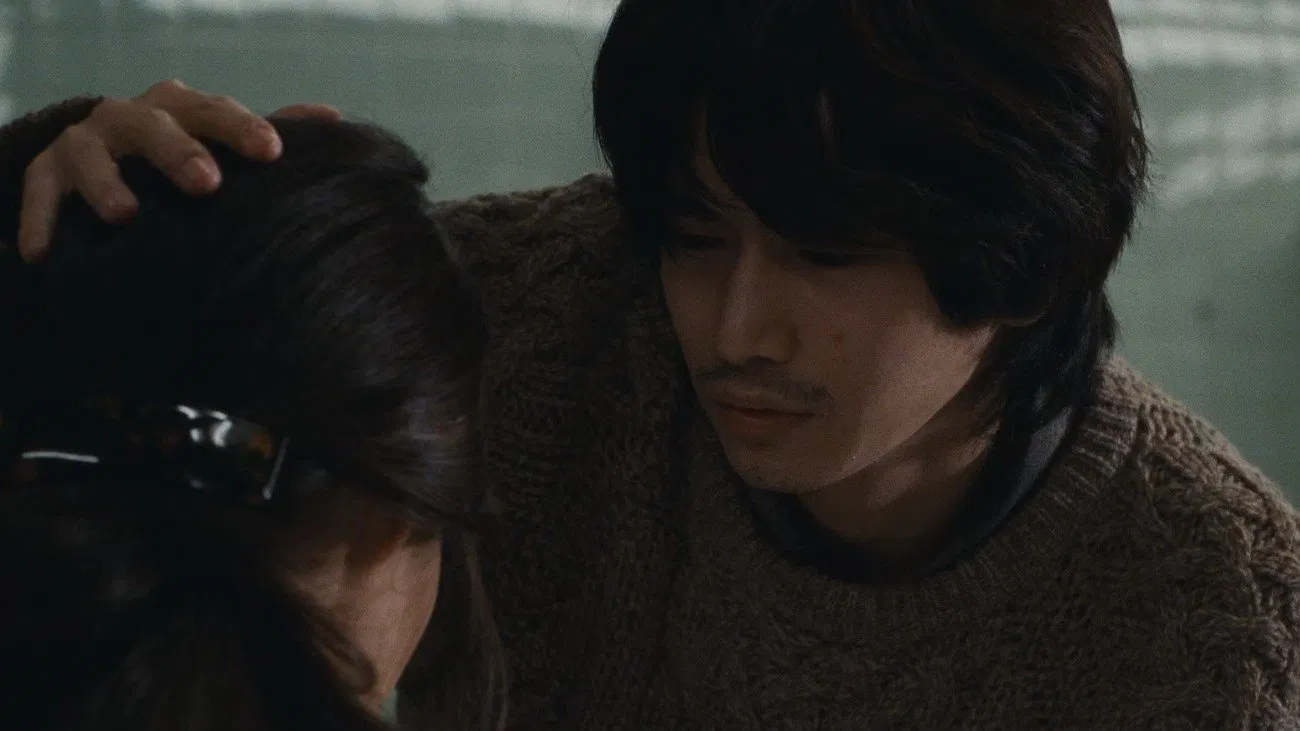

Gruesome as the last sentence definitely appears, it is the main premise of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s critically acclaimed psychological horror film, Cure, released in 1997. Mass murders occur in the heart of Tokyo and Takabe, a detective whose career spans years and whose eyes have witnessed atrocities, desperately attempts to extract information from the killers, who appear to struggle with memory loss after the crime. Only when he immerses himself in the case does he encounter the mastermind behind the killings: Mamiya, a young hypnotist, who, by informally interrogating his potential victims, manipulates them into releasing the most gruesome, and yet the most genuine version of themselves through the act of murdering. The film deconstructs the very binary of hero and villain, poses questions that, once thought about more meticulously, acquire an existential background, and positions the concept of identity under heavy scrutiny.

Mamiya’s act of persuading his victims to commit these heinous crimes might lack morally sound motivation, for it reveals his very own deficits, his distorted desires and perverted thoughts, and yet we can argue that it is a path —however thorny— to liberation for them. Absurd as it might sound, Mamiya offers a tempting, albeit horrific, opportunity to his victims to (re)discover their true identities, to delve into their sentiments and thoughts that moral codes have been suppressing for so long. What is identity, truly? Who are we, why are we here? Such questions seem to be tormenting all the killers; Mamiya, like some deus ex machina, exploits their vulnerability and disarrayed minds in order to act on his own instincts and wishes, which are largely driven by some inexplicable lust for blood and death.

Of course, his intentions and motives are of severely dubious moral quality, although we cannot clearly pinpoint them during the film; he proclaims an inability to remember anything that has occurred before the murders. Amidst a world whose moral codes are constantly debated, whose standards and norms are either under feverish attack or complied with reluctantly, the individual’s perception of identity and of their true self is fluid. Faced with a perpetual sense of an emotional void which is all-consuming, one feels overpowered and begins to seek the missing pieces of themselves elsewhere, entering heterotopias in a perhaps terminal effort to explore and define the capacities of their identity.

After the murders, each killer carves the letter X on the body of the deceased. In a sinister and paradoxical use of the most nihilistic letter in the Latin alphabet, Kurosawa exemplifies how every trace of morality is eliminated in the process of recreating of one’s self. The same could not be said about the identity of the killers; it is ironic that, by eradicating the presence of another individual, the murderers come to terms with the gloomiest, most obscure parts of their identity. We are discussing a death of one that signifies the rebirth of another. Mamiya’s question now has a response: these characters are, in reality, better defined by the word “monsters” rather than humans. It is often said that humans can be worse than beasts, and in the case of Kurosawa’s film, this is exactly the case.

Can anyone escape from the plague that identity crisis constitutes? Kurosawa provides us with a crystal clear, disturbingly ominous reply: no, this is simply not plausible. Cure has never been destined to offer reassuring words of a brighter, more promising future for the individual, and, if anything, proceeds to portray the inherent evil and malice of the human psyche, which we endeavour, some of us successfully, some of us not, to conceal under the façade of a proper citizen, abiding by societal rules and norms that have been imposed on us since the beginning of time. Opponents of Dark Romanticism in the 19th century would warn their audience about the regression of humanity to a primitive state, whereby primal instincts that have been hidden under a thick layer of decorum and morality emerge and define the individual.

There is something within the heart of humans so horrendous that once released, it can wreak havoc. Kurosawa, through the ambiguous Mamiya, takes us back to these ideas that saw the light centuries ago, and yet are still pertinent, in between the fragments of a disconnected society, which has nothing much to offer to humanity, other than its demolition. A sense of constant isolation and alienation from the world around us urges us to continually redefine ourselves within the strict borders of the surrounding society. In Cure, we are faced with a cruel descend into savagery and brutality that possess the individual and allow them to perform the most vulgar acts in the name of being true to themselves.

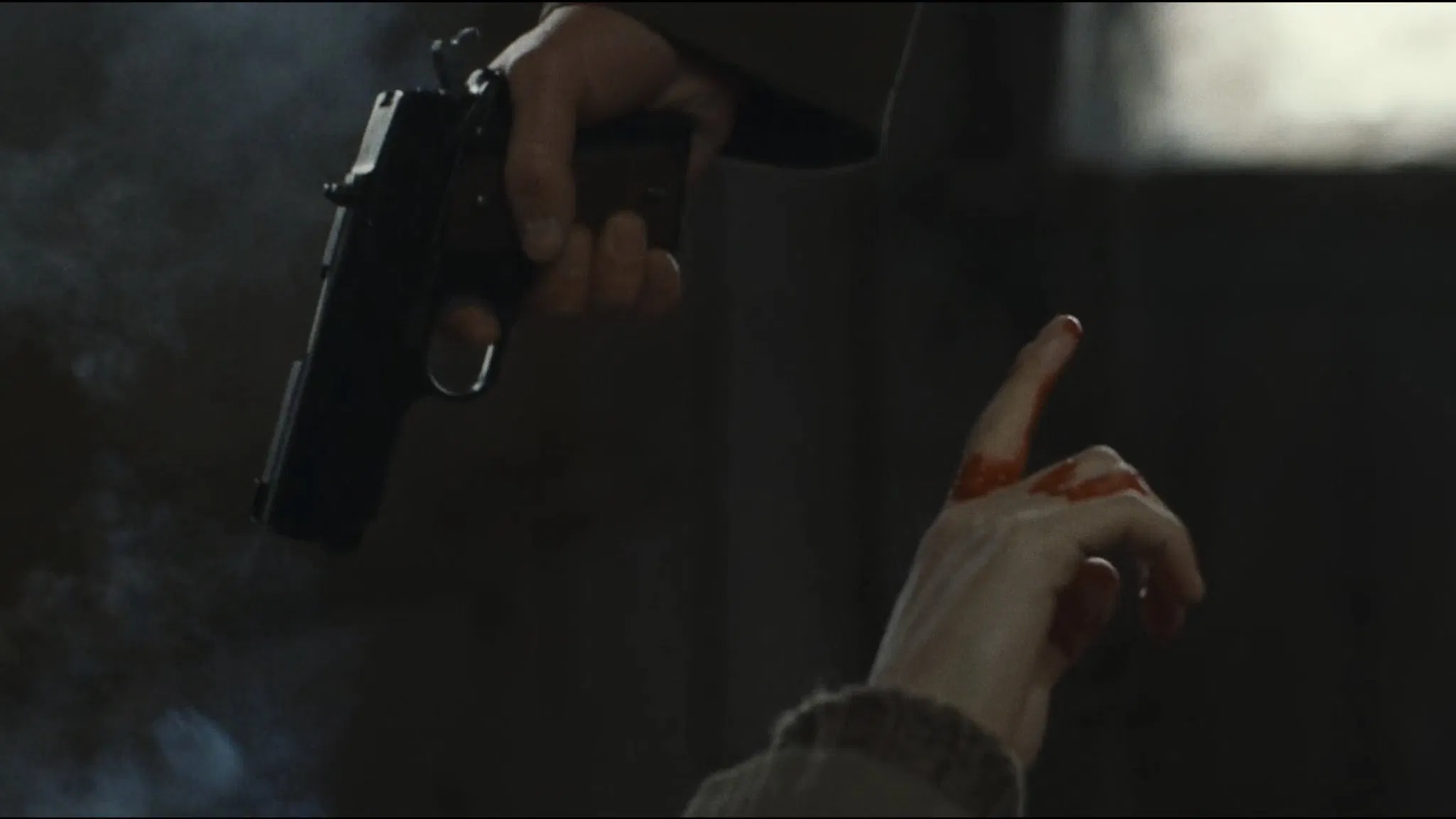

We seem to be oblivious to the fact that we are part of this society, too. Takabe, at one point, vehemently blames society for every struggle bestowed upon him, such as his wife’s illness ,which he claims has been a burden to him. He is incapable of accepting his own reality, blind to any potential deficits he exhibits. Our supposed protagonist, the hero we rush to celebrate from the beginning, is not immune to this disease that has been spreading its veins everywhere, either. Finding himself trapped in an intense internal conflict, he partially, at first, succumbs to Mamiya, confessing to him that he has never been delighted with the circumstances of his life. While we can make an effort to sympathize with Takabe at first, all our expectations are violently crushed when he shoots his nemesis dead.

Eventually, not even our “hero” is able to resist the urge to unleash his truest form and surrender to his instincts and primal drives. Hence, we are dealing with severe ambiguity here; who is the (anti)hero in the story? One might even consider Mamiya a hero, against all odds and all moral constraints, for he is juxtaposed with the conventionally moral individual, and unapologetically allows himself and his victims to indulge in the rawness and brutality of human nature. Takabe’s mind is infiltrated by his opponent’s ideas and, while he claims to be on the right side of history, cannot hold on to the persona of a loving, fair and balanced husband, detective, human. For once you come too close to malice, you might eventually become malicious yourself.

What is the cure to all these illnesses? Is Mamiya’s solution, albeit a harbinger of chaos and disorder, one to consider? And can we ever claim that we are self-aware enough so as not to regress to a primitive state, driven by instincts and bathed in blood? Kurosawa’s enigmatic, mesmerizing Cure ventures to pose such questions filled with dread and anguish, leaving plenty of space for consideration. After all, under all the lustre, we might as well be considered animals ourselves.

References

- Tell Me About Yourself: On Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Cure”. Los Angeles Review of Books. Available here

- Cure: Erasure. The Criterion Collection. Available here