By Dimitris Kouvaras,

When thinking about rising powers, I bet that for most, Poland does not come up as the first pick or even a promising candidate. One would easily think of China and India, both powerhouses of global industry and population, or even Brazil, as the dominant economy in Latin America. But when it comes to Europe, the stereotypical image of a rich and developed, although somewhat sclerotic, West versus a poorer developing East has stuck for good. For some, the entirety of Europe might even be reduced to a place of geopolitical stillness, whose leading role in global affairs has evaporated alongside its colonial past. However, if the focus shifts from global to regional contexts and stereotypes are set aside, room for considering new rising powers suddenly appears, with Poland definitely among them. However, this rise comes with a great deal of uncertainty and ambivalence.

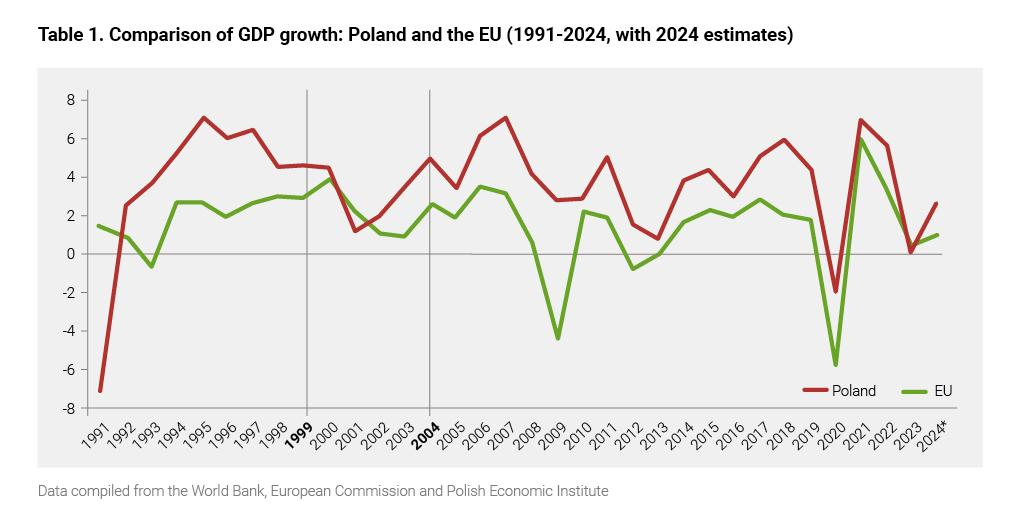

But what exactly gives a country the potential to become a “power”, either globally or locally, as in the case of Poland? What research suggests, and history confirms, is that a combination of factors is required, among which some constants can be singled out: a strong economy, robust demographics, a potent military, and political influence. Economically, Poland has long overcome the struggles of the late communist period, entering the European Union in 2004 and tripling its GDP by 2020, despite the setback of the COVID pandemic. European integration and structural EU funds, of which Poland is the largest recipient, have had a sweeping impact on stimulating growth, whose rate per GDP is forecasted at 3.3% for 2025, standing at three times the expected average of the European economy.

Poland’s economy has profited from cautious fiscal policies, its broad and dynamic consumer base and its diversified industrial sector to stimulate development, which has enabled a recent tangible rise in wages and the allocation of generous social benefits. Meanwhile, inflation has been tamed, and unemployment stands as low as 2.8%, compounding the country’s prosperous image. However, public spending has led to a widening budget deficit, which is nonetheless projected to stabilise in the coming years. Therefore, with its developing economy, rich in arable lands and agricultural output as Europe’s third-largest wheat producer, and with a sizable industry comprising around 34% of its GDP, Poland ticks the finances box of the how-to-become-a-power list.

Demographics, on the other hand, might as well be the country’s weak point. The last three years have witnessed a noticeable decline varying between 1% and 2%, among the sharpest in Europe, while projections for the 21st century paint a rather gloomy picture for the decades to come. Nevertheless, with more than 38.000.000 inhabitants, Poland remains among Europe’s most populated nations, which, considered in the short term, does not hinder its surge in the present geopolitical circumstance. That latter nation is crucial for understanding Poland’s next power coefficient, its political influence. Contrary to structural forces such as the economy and demography, a state’s international role, and especially that of regional powers, is also highly determined by volatile geopolitical circumstances, emanating from geographical dynamics. In that respect, Poland’s position in the heart of the Eastern European plane and right on the corridor which connects the continent’s industrial German core with the immenseness of Russia has been historically pivotal, since it has acted as a buffer zone between two powerful—and often antagonistic—states. What led to the country’s being devoured by its mighty neighbours in the late 18th century has now turned into a geopolitical opportunity, fostered by the unfortunate war raging in Eastern Europe. Given Russia’s expansionist war in Ukraine and the invasion of Crimea in 2014, Poland has become the primary NATO frontline state in the east, which amounts to enhanced strategic influence.

In the context of the war, Poland has turned into a major logistical hub for distributing around 90% of the humanitarian and military aid destined for Ukraine, while being a protagonist in calls to scale off Russian aggression since 2017. With US troops on its soil and valuable NATO air defences, Poland matters. Not least, due to the geopolitical turmoil in Eastern Europe, military spending has been kept high, peaking at 4.7% in 2025 and well exceeding the European median as a percentage of the GDP. Thus, Poland comes to meet—mutatis mutandis—yet another power coefficient, although much of its equipment relies on foreign contractors, and especially the US.

However, NATO-related influence is not the whole story. Poland is also receiving more attention due to its ambivalent position within the EU, a second source of political influence—as well as instability—, which intertwines with the first and has become particularly relevant after the second round of the Polish presidential election on June 1st. The latter meant a marginal victory for the nationalist Karol Nawrocki, who won over the liberal mayor of Warsaw, Rafal Trzaskowski, with a narrow 50,9%. Given the presidential veto power over legislation, Nawrocki, who was the unofficial candidate of the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) coalition, will likely succeed his predecessor in blocking Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s EU-minded legislation and liberal reform acts. Thus, Poland’s ambivalence against the European Union is expected to persist.

While Tusk is supportive of integration and advocates for an independent judiciary concordant with European standards, against the backdrop of former illicit PiS interference and manipulation, as well as ready to rid the country of illiberal legislation, Nawrocki is a stout nationalist advocating no more control by Brussels. Adding to the complexity is the new president’s close ties with Donald Trump at a time when US relations with Europe are heavily tested. Therefore, it is at the juncture of traditional Polish pro-Americanism and reliance on the US for national security versus European efforts for strategic autonomy and a Trump sceptical of European commitments that the political and military legs of Polish political influence meet with the EU, the US, and NATO. Poland thus stands at a double crossroads regarding both its domestic and foreign policy, which, combined with its geographic position and the urgency of the invasion in Ukraine, gives it potential for influencing regional—and by extension European—affairs. Nevertheless, this comes with its own high risk.

Finding oneself at the core of geopolitical developments is never easy. For Poland, this could mean greater global impact and more attention from the EU, but could also mean strategic precarity. Ukraine is a prime example. Although Poland acts as the main aid corridor and a primary refugee destination, it is particularly grumpy about President Zelensky’s habit of addressing only the “big guns” of NATO instead of its neighbour and is equally reluctant to send home troops to Ukraine, not least because of historical tensions between the two. Moreover, Russia’s gaze always casts its shadow over its plains. Consequently, the complexity of its position is once again confirmed. It remains to be seen how Poland, which ticks most of the boxes to be considered an upcoming regional power, will deal with the unforeseen leverage it has gained through the factors analysed above, as well as the disadvantage of internal policy division. It also remains to be seen how long the present geopolitical conjuncture will last. What is certain is that Poland will try to ride the two horses of keeping NATO unified and US involvement strong and maintaining balanced relations with Brussels and a European integrative trend (also defence-wise), at a time when its president and prime minister have antithetical views on the matter.

References

- Conservative historian wins Polish presidential vote. BBC. Available here

- Economic forecast for Poland. European Commission. Available here

- How Poland emerged as a leading defence power. The Economist. Available here

- Power moves east: Poland’s rise as a strategic European player. Danish Institute for International Studies. Available here

- What makes a country powerful? Clingendael: Netherlands Institute for International Relations. Available here