By Vera Rodriguez,

As the world becomes increasingly digital, chips have become a crucial component of digitalization. These technologies are small pieces of silicon that contain transistors, capable of controlling the flow of electrical signals. As seen in part I of this article, these devices are now at the core of global trade, being part of a largely globalized value chain. This is especially the case for cutting-edge semiconductors. However, the apparent structural competition between the United States and China is undoubtedly shifting how countries change of advanced semiconductor production; from big players to smaller ones.

China’s global presence has recorded a steady rise this last quarter of the decade. Now, a lot countries trade more with Beijing in comparison with those that engage in trade with Washington. Moreover, one also has to consider the shaping of the “Made in China 2025” strategy, a blueprint that was designed to turn the country’s economy from the world’s top factory for low-cost goods into a head-state in high-tech and innovative manufacturing. In July 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump followed through on months of threats to impose tariffs on Beijing for its alleged unfair trade practices. Since then, multilateral organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) have become a platform for U.S.-China confrontation, and bilateral trade between both parties has fundamentally changed. One crucial area has been technology.

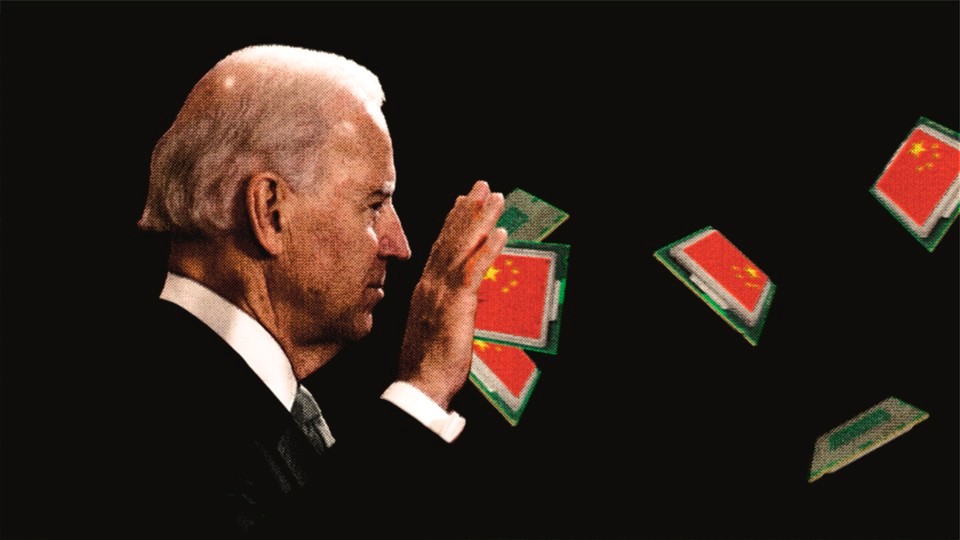

Although this trade confrontation started with Donald Trump in 2018, its successor, the then-US president Joe Biden, passed the “Chips and Science Act” and the “Chip 4 Alliance” to prevent the rise of mainland China in high-end semiconductor processes. With the Chips Act, if a company receives subsidies from the US, they are not allowed to set up plants, invest, or expand existing plants within the country of China. Moreover, the Chip 4 Alliance extends this policy to geopolitical alignments, creating a partnership among Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea, the major semiconductor-producing powers. Other instances of this war around chips included the U.S. prohibition on exporting EUV machines to China, which is crucial for building advanced chips below 7nm. The White House also requires companies to obtain permission to export technology with a node size below 16nm to China. Other narratives accompany these strategies; Washington has proposed slogans such as “ABC,” meaning “Anywhere But China,” signaling a broader, long-term plan of decoupling.

China, in turn, is pursuing self-sufficiency, spending vast public funds to develop its chips, though it remains dependent on foreign equipment, particularly from Europe. Moreover, China has passed legislation that prevents those with U.S. green cards from securing senior positions in Chinese semiconductor companies. Despite heavy investments, China still faces difficulties in order to produce cutting-edge chips because of the U.S. sanctions and its lack in extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography technology. It remains dependent on Taiwan and foreign firms, such as ASML (Netherlands) and TSMC. However, there are signs that these obstacles are prompting China to be more innovative. For instance, a few months ago, the Hangzhou-based generative AI model DeepSeek garnered international public attention due to its lower production costs. Recently, Beijing announced it could produce those chips without EUV machines.

These measures are forcing Taiwan, Korea and U.S. manufacturers to take sides. Enterprises that want to expand in China will have to do so at the expense of losing trade with the United States, and vice versa. Take as an example the case of Taiwan, a complex theme in this delicate balance. On the one hand, semiconductor production accounts for a significant part of Taiwan’s economy, with 20% of its output to the manufacturing industry’s employment, 34,8% of total exports (2021), and 70% of Taiwan’s total trade surplus. It also accounts for an essential share of the world’s economy. Taiwan’s production of chips below 7nm is more than 60% of the global market share. On the other hand, both the Chinese and U.S. markets are crucial for Taiwan’s semiconductor economy. Raw materials are sourced from Japan, equipment is supplied by the Netherlands, the U.S., and Japan, and the U.S. holds intellectual property rights.

To sum up, international actors are being increasingly compelled to make choices and further engage in this trade war. Now, especially with Donald Trump’s second administration and a more assertive approach to global trade, crafting a reliable international network for alternative partners to leverage the influence of the big players seems to be the way forward for middle-sized countries like South Korea, Japan, and possibly Taiwan.

References

- Biden orders ban on certain US tech investments in China. Reuters. Available here

- Jiann-Chyuan Wang. “The U.S.-China Technology War and Taiwan’s Semiconductor Role in Geopolitics”. The Hague Center for Strategic Studies. Hague. 2023.

- Semiconductor design and manufacturing: Achieving leading-edge capabilities. McKinsey. Available here

- Dutch semiconductor interests in Asia. Leiden Asia Center. Available here