By Dimitris Kouvaras,

As we saw in the first article of this series, ancient historiography was a colourful mosaic of approaches to history writing, intertwined with distinct conceptualisations of time. In the Hellenistic and Roman West, time was considered quasi-cyclical, while in the Chinese East, its notion was an integral part of the correlative cosmology of the different elements of worldly order.

Sima Qian was the first prominent Chinese historian whose work is well documented, living in the last two centuries BCE. His magnum opus, the Siji, laid the foundations for the future genres of Chinese historiography through its sections comprising annals, biographies and treatises on various spheres of knowledge, from agriculture to astronomy. Unlike Western Greek and Roman narratives, intended to attribute right or blame through a continuous narrative of the historian’s choosing, the Siji provides a wide corpus of encyclopaedical material in the suitable literary fashion upon which the historical reader can reach their conclusions. However, no more than a century after Qian, conceptualisations of history would change forever, after a series of events in the Roman province of Judea led to the advent of a new religion: Christianity.

Christianity was a revolution in historical thinking, as it promoted a radically new conception of time, imbrued with a novel signification of the historical process: divine Providence. God’s will became the explanatory notion behind the succession of events, which was now established in a linear timeframe, stretching from Creation to the Second Coming and punctured by the advent of Christ, which soon became the focal point for Christian, and then global, chronology. As events unfolded along this line, they acquired their signification through their role in the fulfilment of the divine scheme, which meant that the future Final Judgement became a measure for all past events. History in toto acquired an eschatological meaning; it became history “in future tense”. This line of thought fundamentally changed Western historical writing, dominating it throughout Late Antiquity and Medieval times, while still leaving its mark on the way we think about time.

The linear Christian conception of time was intertwined with an effort to locate Biblical events in time and relate them to the historical present through a continuous narrative by reinventing Chronography, an ancient Greek genre. Eusebius of Caesaria in his Chronological Canons dated the birth of Abraham in 2016 BCE. Living in the third century CE, he invented a new historiographical genre with his Ecclesiastical History, framing it as a divine narrative of salvation up to the reign of Constantine. Eusebius viewed Constantine as a pivotal figure, interpreting his reign as the fulfilment of God’s plan for the triumph of Christianity. Since the creation of the East Roman Empire, European historiography followed two distinct paths. Procopius (5th century CE) is a special case for the Greek-speaking East. An imitator of Thucydides in his Wars, where he narrates the military victories of Justinian along the lines of Providence, he is equally famous for his Secret History, a sweeping criticism of the imperial couple full of lascivious details that would put modern tabloids to shame. As his example shows, elements of classical historiographical methods survived in Byzantine historiography, contrary to the annalistic tradition in Latin Christendom. However, they were part of what now was a hybrid historiographical tradition.

In Latin Christendom, Augustine of Hippo in his City of God, one of the cornerstones of Western thought, set on explaining the sack of Rome in 410 through Providence. His work entails a societal self-reflective vision that ponders questions of empire destruction and human righteousness based on a dualistic vision of society: the glorious city of God (civitate Dei) is mingled with the daemon-revering Earthly city (civitas terrena) in a teleological journey guided by Providence toward their separation at the end of time. Augustine rejected the cyclical view of history prevalent in Greco-Roman thought, emphasizing instead the singular significance of Christ’s Incarnation as the central event of human history. His eschatological perspective saw historical events as part of a divine plan, culminating in the Last Judgment. This theocentric vision not only shaped medieval Christian historiography, but also provided a framework for interpreting the church’s mission on Earth and imperial fortunes. A few centuries later, it would be used by Otto of Freising to vest the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederik I Barbarossa with the ideological prestige of Rome, presenting him as the cultural and political heir of the Imperium, which was transmuted through the Carolingian Franks, thereby establishing the concept of translatio imperii.

During the medieval period, historical writing primarily took the form of chronicles and annals, while hagiography also became a popular genre. These works, often compiled in monasteries, were initially designed to record significant ecclesiastical and political events in a linear format. They reflected history as a providential narrative, punctuated by divine interventions and miracles. Chronicles such as Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731), exemplify this approach, intertwining the history of nations with the progress of Christianity. Bedes’ work, a creative combination of oral and written sources implying selection, reflects a “praise-and-blame” approach to history as an educator of the powerful, designed not just for private reading but for performance, through oral recitation, which characterises many contemporary works. By the High Middle Ages, chronicles increasingly contributed to the formation of national identities by creating divinely inspired genealogies. Authors began to link the histories of their peoples to divine plans, framing their nations as chosen instruments of God’s will. For example, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136) mythologized the British past, tying it to the legendary figure of King Arthur, while French chronicles glorified Charlemagne, to ferment a nascent form of national consciousness. Slowly, vernacular use started building up alongside Latin.

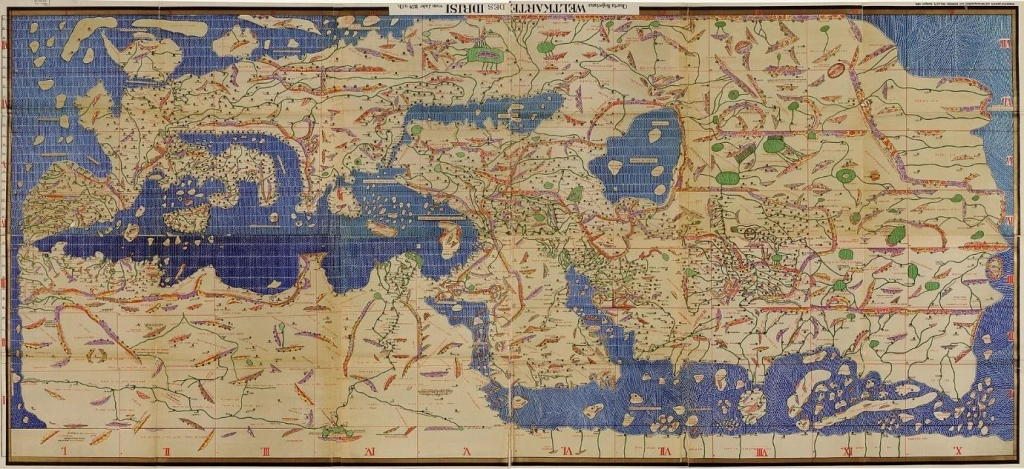

While Christian medieval historiography dominated Europe, Islamic historiography developed its own traditions. Muslim historians, influenced by the Qur’anic view of history, emphasized the unity of humanity under God, thus Early Islamic historians, wrote extensive universal histories, weaving together Islamic narratives with pre-Islamic traditions. Al-Tabari’s History of Prophets and Kings reflects a linear view of history, akin to Christian eschatology, highlighting the moral lessons inherent in historical events. Initially, strict rendering and verification of the prophet’s words were emphasised through hadiths (=testimonies), although a more intellectual outlook was soon assumed, embracing the use of empirical research and critical methods. Ibn Khaldun, living in the 14th century, can be considered the pinnacle of this trend. In his Muqaddimah (Introduction to History), he pioneered a critical and synthetic approach to historical change, analysing the rise and fall of civilizations through a consideration of various factors, including climate, economics and cultural traditions, while underlining the importance of social organisation for human survival. This distinctive synthesis of faith and reason remains a unique example of medieval scholarly literature.

Although the concept of the “dark ages” is still prevalent in the popular imagination as denoting a period of stagnation and ignorance, an overview of early Christian and medieval historiography, including the Islamic world, attests to the opposite. These authors might not be as famous as Herodotus, but this proves no reason to brush them aside. Christian historiography, although far from the modern scientific conception of history, remained rich and diverse. Its debasement versus the revered Greco-Roman “classics” informing contemporary views is not so much due to the impotence of the former and the superiority of the latter as to the negative critique medieval historiography received in the Renaissance, an era which hailed the rediscovery of the Greek and Roman civilisations and made a decisive (but by no means complete) step away from medieval theocentrism. In the next article, we will explore its story…

Reference

- Woolf, Daniel. A Concise History of History: Global Historiography from Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. 2019.