By Katerina Taxiaropoulou,

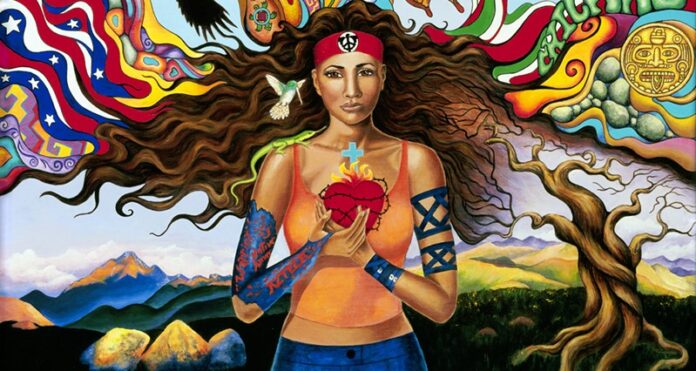

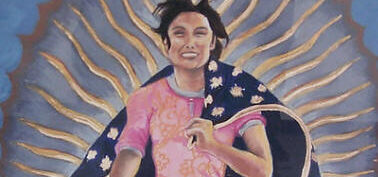

A mistress, a mother, a sorceress, a healer… Inés Alfaro is too much. In her short story “Eyes of Zapata”, Mexican-American writer, Sandra Cisneros, creates a female protagonist who thwarts patriarchy’s essentialist definitions, identifying as neither the virgin, nor the prostitute, but rather assuming an amphibious, multiple subjectivities. Within the oppressive superstructure of machismo, women are defined along the binary of the Virgin Mary and La Malinche, two traditional female archetypes. The first one describes the “pure” mother figure, a “role model” for young Latinas (Morales and Pérez 247). On the other hand, the second one constitutes a “cultural symbol” of prostitution and female vice, a woman in history “viewed with contempt” for serving the Spanish conqueror, Cortés, as a mistress and gifted interpreter (“La Malinche”).

1. Deconstruction of cultural archetypes

For the villagers, Inés resembles Malinche, as she is mistress to a revolutionary, whose actions have brought about an immense amount of pain to themselves and their land. She is the opposite of Mother Mary, because she is deeply in touch with her senses, a fact that allows her to engage in sexual activities, as well as witchcraft. By the irreducibly complex nature of her existence, however, Inés cannot fit in this liminal space of duality. Instead, she occupies what Candelaria terms a “wild zone”, that is a radical multipositionality, a necessary oscillation to pursue an “affirmative identity of the self” (250). Inés blurs the mother-prostitute divide, being both a sexually free woman, and a remarkably nurturing mother. With the selfless love of Mother Mary, for example, she feeds starving Malenita, while she eats only if there is something left. Inés, therefore, escapes any single-axis definition, as she circumvents rigid identity categories, without ever realizing one fully.

Also, Inés evades an identification with the Mexican archetype of the subservient female soldier, revising it through active female solidarity in the struggle for survival. Within the nationalist narrative of the Mexican Revolution emerges the icon of La Soldadera, the female revolutionary, stereotypically characterized by “self-sacrifice and suffering” in the service of the war’s higher cause (Curiel 422). Women’s anticipated action is therefore reduced to a mother-like care for male fighters. Inés has long served that role, reassuring sleeping Zapata like her helpless “bebisito”. Her motive however is different, since more than his political sister, she identifies as his lover. Sadly, her selfless love is betrayed, as Zapata already has a wife. Simultaneously, the revolution betrays its promise of liberation, bringing only famine and destruction instead.

After so much suffering, Inés can recognize the oppressive male order in her predicament, and this recognition becomes “an impetus for her to question and ultimately change [it]” (Rojas 150). In a quest for survival, she turns to the females in her family for reciprocation of love and care, building among them a relationship of enacted solidarity. In this spirit, she embraces her mother’s inheritance. She actually uses her gift of curanderismo to care for her sick Tìa and her daughter, who was also abandoned by Zapata, unlike her brother, confirming, thus, the patriarchal cycle of consistent and recurring female rejection. To end it, these women first need to articulate their independence.

2. Radical Self-Definition

Disrupting a matrilineal order of silence, Inés initiates a discourse of resistance, yielding the power of language from male dominion to secure a future of self-definition for women. As Rojas notes, a diachronic thread connects Maria Elena and Inés to the figure of La Malinche, suggesting a “long history of inscription” (152). Indeed, all three women have been similarly misrepresented by male authorship. While Malinche was “a brilliant mind”, her historical subject was minimized to a “brief mention” as Cortés’s mistress (“La Malinche” 3). The villagers refer to adulteress Marìa Elena only to curse her name, and Inés too as one of Zapata’s pastimes has been minimized to “a historical footnote” (Curiel 404). The strange sound similarity between Malinche and Malenita creates concern about the future, but this is alleviated as Inés awakens into awareness of the inscriptive power of words.

Reflecting on the curses “bruja, nagual” (witch, animal-like woman), Inés doubts their restrictive meaning. As she recognizes and challenges the male privilege in her native language, she begins to craft an original, female-inclusive discourse. She therefore poses the bold question: “Why not hombreriega?” (a woman who is involved with multiple men). As awkward as the word ‘manizer’ may sound, “speaking the unspeakable” is key to a successful act of resistance (Rojas 153). Seizing the right to language, Inés discovers her power to create her own subjectivity and marks the beginning of self-determination for women. As she informs the readers, Malenita’s daughters will identify as “solteronas”, single women. Earning their living through curanderismo, they will come to materialize their grandmother’s dream of independence.

In a final heroic act of liberation from the patriarchal imperative of violence, Inés points to the futility of the war, choosing love as her own radical identity marker. During the revolution, Inés has been victim of the unrestrained brutality dictated by the culture of machismo. As a gifted visionary, however, she is able to see beyond her own body and through “all pain, not just female” (Thomson 416). Yet, even though she shows compassion for men too, she surely does not excuse their causing nine years of futile suffering. As Rojas underlines, Inés knows that a “new elite simply replaces the old” (149). With her omnipotent eyes, she sees her son selling the Zapata name to the PRI. In such acts of male betrayal, Inés recognizes “a manifestation of … a failure of love” (Thomson 415). Behind the war’s frustrated promise of freedom, therefore, stands men’s emotional deficiency.

Inés, on the other hand, as a “fully aware feminine self”, has the power to ingest all the pain of the past and through it claim her identity (Thomson 415). She then comes to form a new, radical definition of freedom as the ability to love until we are “something bigger than our lives. And we can forgive, finally”. Through this superhuman forgiveness, Inés defeats all those patriarchal structures combined to stifle her subjectivity. Although she cannot erase all the years of oppression and start anew, living practically free from patriarchy, the reader may keep that she has achieved a liberation of the mind, and that is enough to hope for change.

References

- The General’s Pants: A Chicana Feminist (Re)Vision of the Mexican Revolution in Sandra Cisneros’s ‘Eyes of Zapata’. muse.jhu.edu. Available here

- The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Clinical, Applied, and Cross‐Cultural Research. researchgate.net. Available here

- Sandra Cisneros’s Modern Malinche: A Reconsideration of Feminine Archetypes in Woman Hollering Creek. journals.lib.unb.ca. Available here

- ‘What is Called Heaven’: Identity in Sandra Cisneros’s ‘Woman Hollering Creek’. proquest.com. Available here

- La Malinche, Feminist Prototype. jstor.org. Available here

- Cisneros’s ‘Terrible’ Women: Recuperating the Erotic as a Feminist Source in ‘Never Marry a Mexican’ and ‘Eyes of Zapata’. Jstor.org. Available here