By Dimitris Kouvaras,

“United by music” was this year’s Eurovision motto… or at least it tried to be. In fact, it was a wannabe motto if anything else, as the circumstances of the contest and how it unraveled in Malmö have made apparent. Despite the EBU’s best (as the phrase goes) efforts, unity was markedly missing from the show. And it wasn’t the only one, for another important virtue was also absent, albeit less saliently: honesty. If you are surprised to read that, I urge you to consider just one statement, explicitly made during a harmless parodical sketch about Sweden’s multiple wins but implicitly foregrounding the entire image-making of the EBU. It was none other the one demarcating the contest as “apolitical of course”. To anyone in Europe who has watched the news in the past days, let alone the competition itself, it must be clear that this year’s Eurovision was as much apolitical –and therefore honest– as it was united, which means not at all.

Politics is a quite pervasive social realm, a fact that is unfortunately often underestimated or neglected. Not only does it encompass national politics, flags and emblems –its more obvious forms– but it also stretches to include all iterations, opinions, actions and decisions that can be impactful on the freedoms and restrictions of people’s lives, as well as on the inclusion or exclusion of certain groups from recognition in the public realm. That’s an improvisational definition, yet I hope it reveals the point of how naïve EBU’s statement on apoliticality is. Regardless of national politics, Eurovision has been (implicitly) political for years in the social realm, by promoting minority participants and legitimizing diverse gender categories, sexualities and nonconformist attires. Nemo, this year’s winner, is a prime example of that. The positiveness and humanity behind such a promotion of diversity and the existence of certain constraints –such as the inhibition of the showing of the non-binary flag, which was nonetheless performed without sanction– doesn’t refute the political aura it carries with it.

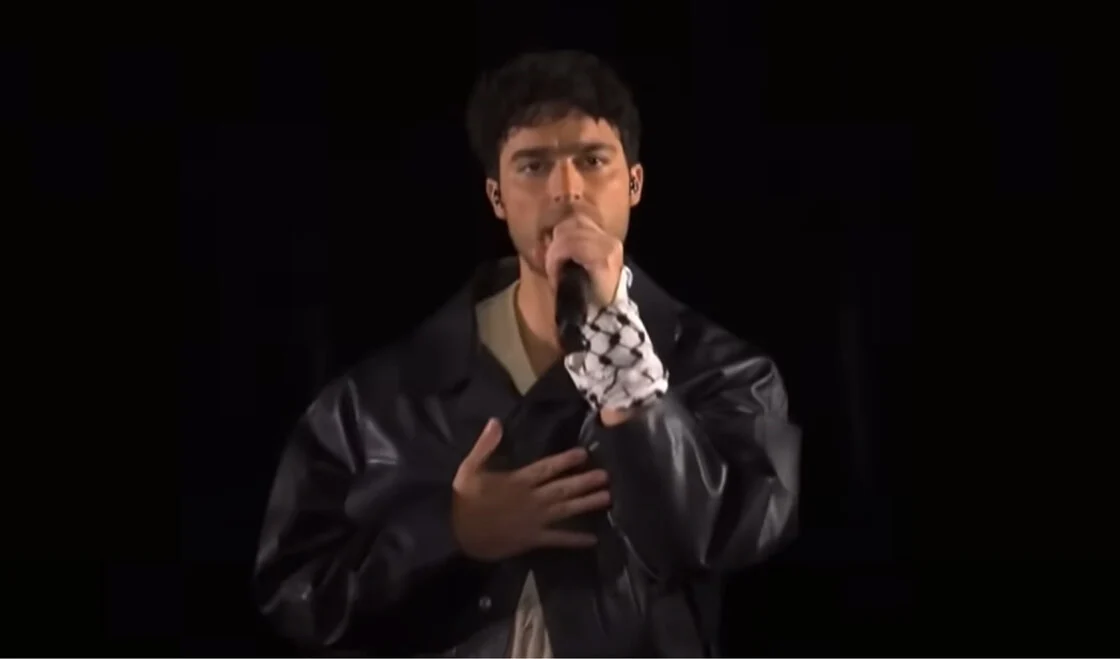

Now, let’s cut to the chase and turn to national politics, which are by far more tantalizing. While Nemo got to show the non-binary flag, Swedish-Palestinian Eric Saade was rebuked for wearing an otherwise discreet –yet symbolic– Palestinian scarf. On top of that, all recordings of his performance disappeared from the official channels of the contest, just because this piece of cloth was deemed scandalous and a political move. It was political, indeed, but so were many other moves within Eurovision’s recent history, some of which stemmed directly from EBU decisions. In 2021, Belarus was disqualified because of a lack of credibility and respect for human rights from the national broadcaster, and Russia followed suit the next year due to its invasion of Ukraine. On that year, it was Ukraine who won, in a symbolic move of European solidarity. No apoliticality took place. Yet it did this year, in defense of the Israeli participation, which was targeted both by activists and delegations in light of the disgraceful treatment of the Gaza conflict.

This was probably a move to save face and keep spirits at bay against rampant criticism for this participation clearance, which was granted even though the Israeli government has received international condemnation regarding its handling of the Gaza conflict, which is more resemblant of genocide than of an anti-terrorist operation. Besides a disproportional civilian death toll, Israel has induced food shortages, deprivation of humanitarian aid and medical supplies, as well as mass displacement to the detriment of the Palestinian population of Gaza, and all that amidst unapologetic nationalist fervor. The Israeli national broadcaster and EBU member, Kan, is not under direct government influence, often finding itself in Netanyahu’s fire line, and thus cannot be considered complicit, yet this doesn’t suffice to properly justify EBU’s decision, or lack of sensitivity. It can easily be inferred from the original song proposal called “October Rain,” which included lyrics calling for the “writers of history” to stand with Israel, that the country’s participation was not intended to be neutral. The current song “Hurricane” is based on the same tune and is the product of EBU pressure for a change to avoid disqualification, as the original was deemed too political.

The issue is that, despite the change, the very admission of such a contested participant (given the factual war and human rights violation background) is a move with political connotations, which are not to be ignored. Sadly, in a competition based on the principle of nation states, and under the auspices of an agency resting on similar foundation, the distinction between the state –and by extension its government– and its delegation is often hard to make, at least in terms of appearance and public reception. This is why Eden Golan faced such fierce –and exaggerated– opposition. However, this also means that the legitimation of the Israeli delegation –which, viewed from an artistic or fair procedure point of view, did have its merits– could in viewers’ eyes easily translate into legitimation of a state and a government responsible for gruesome war crime acts. After all, Israel had the privilege of waving its national flag throughout the contest in a way totally compatible with nationalist symbolism, while any symbol of the other side in the conflict, Palestine, which is the one indisputably suffering the most, was strictly prohibited. In a world where almost everything is political, Eurovision pretended that it’s not, while it employed asymmetrical political treatment and covered up the negative reactions with fictional applauses. This was no solution. It was dishonest for everyone and debasing of the competition itself. Artificial unity has no value; it breeds further polarization.

In theory, art can be separated from politics. However, that cannot be the case in a competition based on the principle of nation states. Even if it were, for the principle to apply symmetrically all political or national symbols should be open to display or not, as –in this ideal scenario– they would remain independent to the core of musical expression. In reality, things are different. Eurovision 2024 failed to acknowledge or was reluctant to admit to its own political stance by trying to keep everyone content through a supposed neutrality. As a result, it exacerbated tension and debased expression. The booing against Golan and the mockery of the calls for Palestinian liberation by her and her team are prime examples of that debasement. These instances might seem funny or foolish to some, but the very fact that they do so is alarming and damaging, since lives are still being lost and people are still suffering. People are currently living amidst debris, not sitting in dressing rooms, and that is not funny at all.

References

- Eurovision says it’s “apolitical”. History says otherwise. Vox. Available here

- Israel says it will edit song lyrics to avoid being disqualified from Eurovision. Times of Israel. Available here

- Israel’s Eurovision contestant Eden Golan shares her very unusual rehearsal strategy as she prepares for the live final amid huge backlash – as organisers prepare ring of steel for event’s most controversial-ever edition. Daily Mail. Available here