By Dimitra Gatzelaki,

To Romantasy or not to Romantasy?

As a reader (mainly) of classics and fantasy, this dilemma has been buzzing in my head for some time. Last week, when visiting one of the bigger bookstores in downtown Thessaloniki, I noticed something that’s been subtly taking root there for a while, and is now in full bloom: their English book selection comprised, roughly, of 60% diverse genres like classics, contemporary and romance novels, while the other 40% (a fairly big number, if you think about it) belonged to the fantasy genre, but slightly… shifted. These novels boasted a (high or low) fantasy setting brimming with magic, dragons and fae, no different than your average fantasy novel really; but, after a quick glance at their synopses, I found that their focus was placed not in mythical quests or allegories, but romance. Of course you’ll recognize some of the authors of this blooming fantasy subgenre: Sarah J. Maas, especially, but also Holly Black, Jennifer L. Armentrout and Rebecca Yarros (the only one I’ve read and would recommend out of these is Holly Black). Even if you consider yourself an occasional reader, I’d wager on the fact you’ve heard of A Court of Thorns and Roses or, more recently, Fourth Wing.

In a nutshell, the “trailblazing” or innovation of these (mostly female) authors stems from the fact that they chose to tread on a path in fantasy fiction that’s often neglected, and in this process birthed a whole new subgenre: romantasy. Linguistically speaking, this (relatively) new word is an amalgamation, a blending, of the fantasy and romance genres.

And yet, has not fantasy with romantic elements existed ever since the genre was conceived? Take, for example, Tolkien’s trilogy The Lord of the Rings from 1954, and the romantic subplot between Arwen and Aragorn. But no one would ever claim that Tolkien’s trilogy was a romantasy. So, what actually defines a romantasy novel? And what’s the source of its allure?

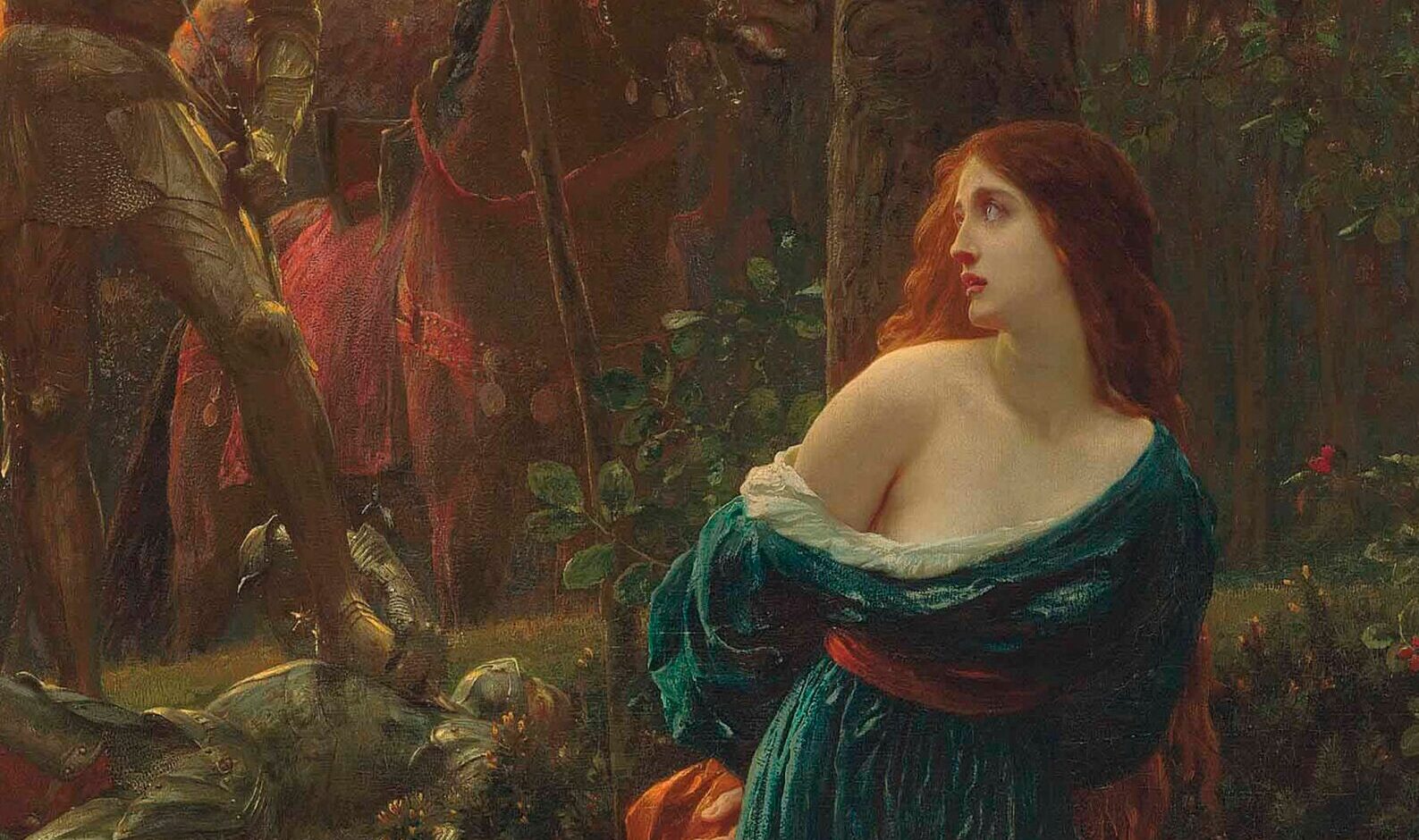

To start, despite romantasy’s status as an offshoot, a branch of fantasy, another compelling lineage emerges: the Gothic. In her article, Kayleigh Donaldson elaborates on this perspective, writing, “the blending of speculative fiction with romance is an old concept. One could argue that its roots lie in Gothic fiction, where innocent maidens ran through the darkened corridors of crumbling castles, and the monsters within were thinly veiled metaphors for rampant desire. What are fairy tales if not a blending of the fantastical and romantic?” If we tread along this standpoint, we can reach the conclusion that romantasy is essentially romance set against a fantasy backdrop, with roots lying in the Gothic legacy. Maddy Mussen aptly encapsulates the subgenre in remarking that “[romantasy] books follow a reliable template: a spunky heroine with a quest and an unusual, otherworldly male love interest with anger issues”. Well, romance novels have been on the shelves for a very long time; what, then, sets romantasy apart, and where does its appeal lie?

First and foremost, I’d argue, in its opportunity of escapism. As a genre, fantasy by definition transports readers to far-off realms, where the fantastical and absurd are commonplace. The themes of the fantasy novel, as well as the issues it raises, remain inherently human; yet they’re acted out on a different stage, with their agents being creatures like fae, vampires, mermaids, elves or all sorts of monsters. To readers, romantasy brings on the added element of romance: the hero or heroine’s love interest takes center stage, pulling readers into distant worlds while also immersing them in a gripping love narrative. This need for escapism has always been there, yet the era of the pandemic, coinciding with the surge of romantasy, has intensified it. Literary agent Alice Caprio has also highlighted that “the post-pandemic desire for feel-good fiction has also led book buyers to increasingly seek the escapism that fantasy provides, combined with the familiarity of romantic fiction”. And so it becomes easy to conclude that, for many, the genre of romantasy acts as a safe place, a refuge. There’s little to marvel at here.

Another, even stronger, reason for romantasy’s increasing appeal is that it sets its focus on the female experience. Most classic fantasy and science fiction novels have been written (primarily) by and for men, centering the male hero in a space where women briefly graze the margins. This can be seen even in the canon of fantasy and sci-fi, in works such as Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Frank Herbert’s Dune or even C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia series. As Anne Perry aptly puts it, mainstream sci-fi and fantasy has tended to “privilege the male gaze and male experience for decades… Female characters in these books were limited in number and tended to be sexpots, sexy villains, damsels in distress, wise old women, sexless just-one-of-the-guys buddies, or complete wet rags: or, to quote Shirley McLain’s formulation, hookers, victims and doormats.” This characterization is also very reminiscent of how women were depicted in male-written Gothic fiction as well; take, for example, Stoker’s Dracula or Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto.

If we consider this pattern, the appeal of romantasy to female audiences becomes a lot clearer. Women crave to immerse themselves in fantasy worlds where they’re not confined by male-centric perspectives; they crave to see themselves as protagonists, not in the narrative margins. This surge of romantasy in the last few years could indeed be viewed as a push towards equality, as it signals a shift towards narratives where women are proactive agents shaping their own destinies, rather than relegated to the sidelines as mere “sidekicks” or “distractions” to male heroes. And this surge, I believe, may also prompt male authors within the sci-fi and fantasy genres to portray women as complex individuals driving their own narratives, rather than merely supporting roles in someone else’s story. Here’s hoping for that.

References

- Romantasy is Everywhere Now, But Its Legacy Long Predates BookTok. Paste Magazine. Available here

- Sex, dungeons and dragons: are you ready for romantasy? The Standard. Available here

- The BookBrunch Report: The rise of romantasy. BookBrunch. Available here