By Lisa Bensoussan,

As an admirer of Annie Ernaux’s work, I impulsively purchased one of her collections of novellas that I stumbled upon. Within the texts, I encountered an essay about literature and politics, a subject I did not anticipate from Ernaux, despite its alignment with her social background. One quote from her resonated deeply with me: ‘I will avenge my people’. Indeed, Literature has long been regarded as a realm of imagination and creativity, seemingly detached from the world of politics. However, as we delve into the complex interplay between books and politics, we uncover a nuanced relationship that defies the boundaries previously drawn. This article seeks to unravel the layers of this relationship, highlighting how literature, despite its artistic origins, is inherently intertwined with political undercurrents.

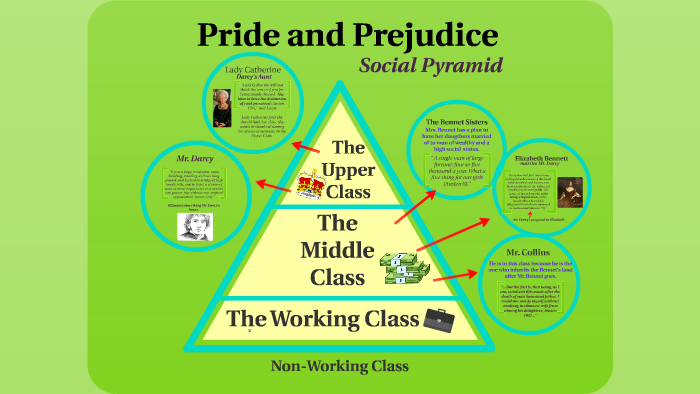

Literature’s purported detachment from politics is debunked when we recognize its role as a mirror reflecting society. Ernaux is not the only one to approve this, as George Orwell said ‘no book is genuinely free from political bias’. He also added “the opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.” Classic and modern works are products of their times, inherently intertwined with prevailing societal contexts. From Jane Austen’s critique of class dynamics in Pride and Prejudice to Margaret Atwood’s dystopian exploration of gender in The Handmaid’s Tale, novels often subliminally encapsulate the spirit of the time. By examining the circumstances in which authors write, we unveil the social tapestry that influences their narratives, blurring the line between art and the political undercurrents that drive it.

While some literary works might outwardly appear apolitical, they frequently carry implicit political stances embedded within their narratives. Authors, consciously or not, infuse their stories with personal perspectives, backgrounds, and biases. Whether F. Scott Fitzgerald:’s critique of the American Dream in The Great Gatsby or Gabriel García Márquez’s social commentary on the tumultuous history of Latin America in One Hundred Years of Solitude, these authors weave political subtleties into their stories. By understanding the intrinsic connection between an author’s life and their work, we illuminate the latent political threads that guide their creative expressions. They also harness the potency of allegory and symbolism to transmit these subtle political messages. These encrypted elements invite readers to delve deeper, unveiling layers of meaning. For instance, George Orwell’s Animal Farm employs farm animals as allegorical figures, illuminating the perils of totalitarianism. Through the various metaphoric techniques, literature conceals political discourse within narratives, engaging readers in a process of interpretation that transcends the overt.

Literature emerges as a dynamic platform for dismantling societal norms and power dynamics. Texts such as Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale offer critical perspectives on gender inequality and patriarchal systems. This work confronts authority head-on, encouraging readers to question the established order. Through adept narrative devices, novels open space for dialogue, exposing the fault lines within society’s structures and fostering contemplation of alternative paradigms. Both fictional and non fictional prose wield the power to mold public sentiment by offering glimpses into marginalized viewpoints. Texts like Gaël Faye’s Small Country illuminate forgotten narratives -here the civil war and genocide that occurred in Rwanda-, expanding understanding. Literature acts as a catalyst for discourse, driving awareness and, at times, sparking social movements.

Literature possesses the remarkable capacity to shape public sentiment through its portrayal of marginalized perspectives. Consider Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, which vividly conveys racial injustice, influencing readers’ views on civil rights. Equally impactful is “The Color Purple” by Alice Walker, which confronts gender and racial oppression, sparking conversations about intersectionality and equality. Literature triggers a gradual evolution of ideas, its impact accumulating over time. Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” raised ethical questions about scientific advancement, shaping contemporary discussions on technology and ethics. The subtlety of literature lies in its ability to infiltrate collective consciousness, fostering nuanced perspectives and inspiring enduring social transformation.

Writers encounter ethical quandaries when delving into political themes, as their words wield societal influence. The symbiotic relationship between artistic freedom and societal responsibility prompts contemplation. Orwell’s cautionary words in “Why I Write” underscore the need for truthful engagement, mindful of literature’s capacity to shape minds as one of his desires was “to push the world in a certain direction” in every person. Masters of the craft deftly navigate the divide between didacticism and subtlety in conveying political messages. Embracing ambiguity grants readers space to interpret, like in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, which stealthily addresses bioethics. Balancing these challenges, authors construct narratives that provoke thought while honoring the reader’s autonomy, making literature a dynamic arena of ethical exploration.

To conclude, in the intricate interplay between books and politics, a profound symbiosis emerges. From the subtle allegorical tapestries to the transformative power of narratives, literature’s ability to shape perceptions and inspire change is undeniable. As writers navigate ethical quandaries and strike the delicate balance between artistic expression and societal impact, literature becomes a dynamic force, engaging readers in dialogues that transcend time. With each turn of the page, novels invite us to explore the intricate layers of our world, reminding us that within its embrace, politics and art are forever entwined, shaping the course of human thought and progress.