By Maria Koulourioti,

How did the word corporation got integrated into the concept of incarceration?

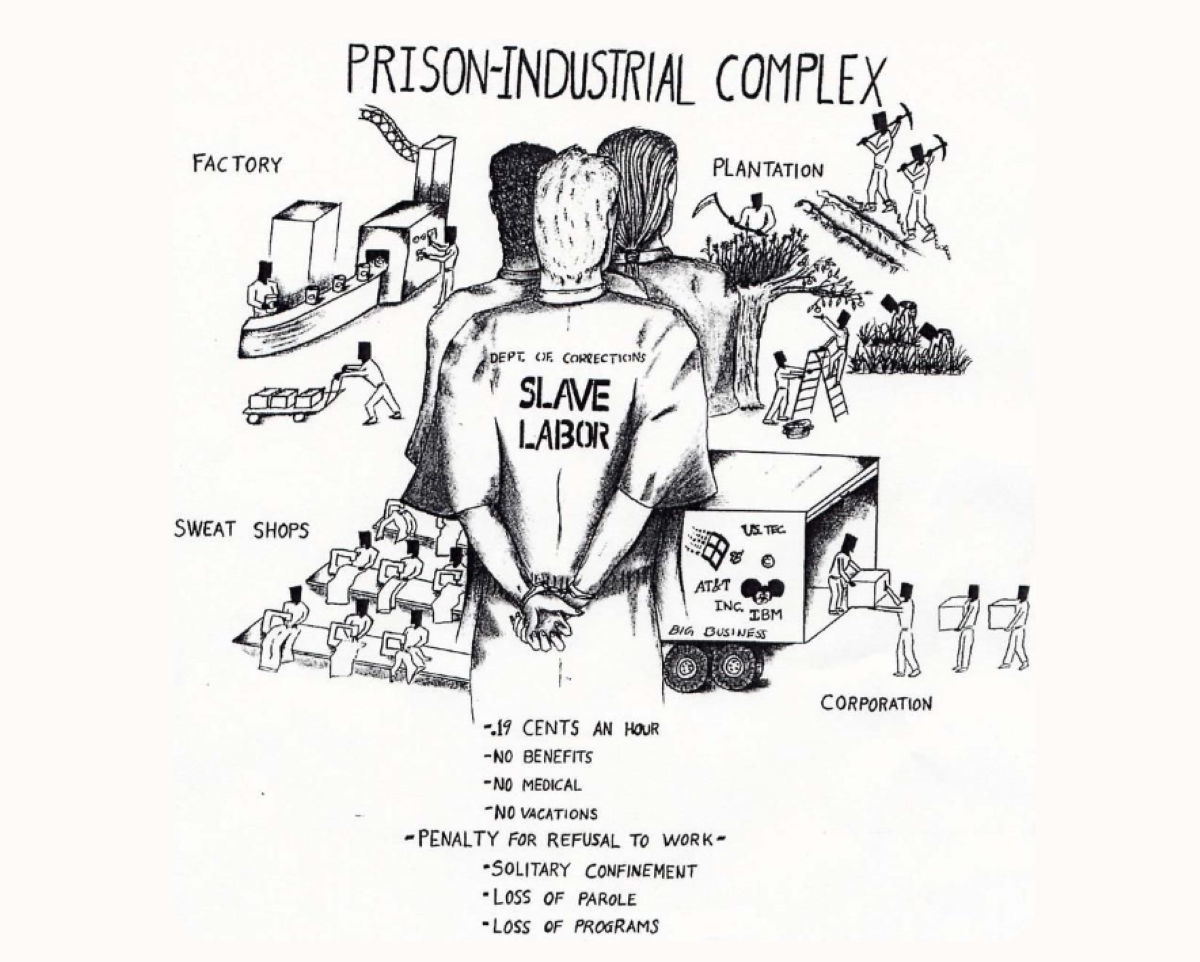

In the 1970s, two contemporaneous phenomena developed in rural America: employment losses owing to deindustrialization and jail growth due to mass incarceration. Early American prisons were generally privately run, housing criminals awaiting trial and debtors awaiting payback while charging local governments and creditors holding fees. Following the establishment of the first publicly-run jail in Pennsylvania in 1790, private company engagement in imprisonment was mostly limited to supplying contractual services such as meal preparation, medical care, and transportation. The convict leasing system in the American South, in which private companies paid public jails for forced prisoner labor, was a notable exception to the relative separation of public punishment and private business in the nineteenth century. While promoters of the prison industrial complex offered rural America an economic lifeline, others questioned the economic benefits of jail openings. While jail expansion increased government employment modestly, it negatively impacted private employment. Prison openings, in particular, were connected with lower job opportunities in manufacturing, finance, and recreational services, with no effect on occupations in construction, wholesale, and local retail sales. As a result, the promises of increased employment in jails were mostly broken.

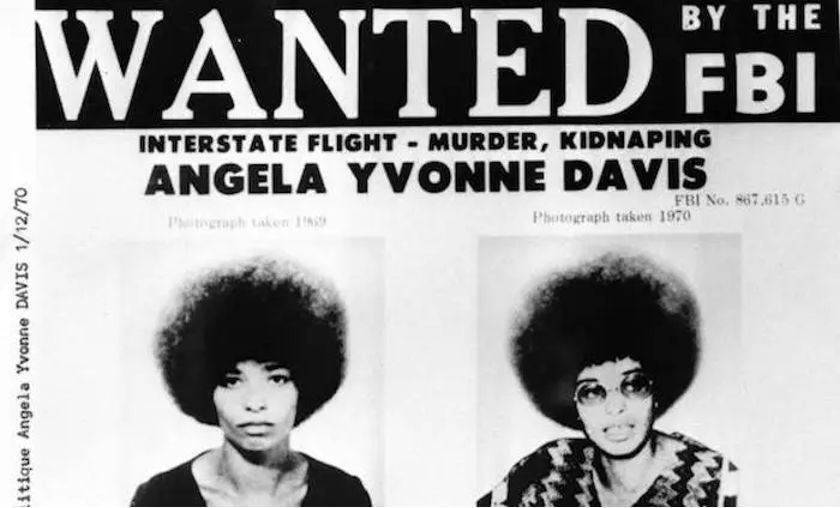

Angela Davis is the academic and political activist who gave an intersectional perspective on the prison-industrial problem, as it evidently charges socially and politically disadvantaged groups. Davis was accused of conspiracy, abduction, and murder in 1970. Her detention spurred an international effort to free her. She was cleared of all charges in 1972, following a high-profile trial, leading to her becoming a prisoner rights advocate and a founder member of Critical Resistance, a national organization devoted to the abolition of the prison industrial complex.

Angela Davis cites earlier struggles, notably slavery, lynching, and segregation, to highlight the idea that prisons can be abolished in the book. She discusses how people act as though incarceration is unavoidable and refuse to reform it, claiming that we take the prison system for granted. It’s mind-boggling that two million individuals in America are incarcerated, in youth institutions, prisons, or immigration detention centers. The institutions are mainly Black, Latino, and Indigenous; those groups have a higher likelihood of going to prison than acquiring a good education.

People who are oppressed are being exiled at an alarming pace to areas with authoritarian regimes, brutality, sickness, and isolation technology, which exacerbate mental health instability. In fact, rather than psychiatric facilities, more persons with mental diseases are housed in jails.

Surprisingly, the United States was able to imprison so many individuals with little public opposition. The government’s most successful and effective program is mass imprisonment, but the public has turned a blind eye to it. How did they manage it? Perhaps it was the notion that building jails would make people feel safer. Ruth Gilmore characterizes it as “a geographical solution to socio-economic problems.” People wanted to think that jails would not only reduce crime but also generate economic possibilities such as rehabilitation of blighted neighborhoods. During the Reagan administration, a huge number of people were imprisoned. Reagan felt that “tough on crime” policies would reduce crime. However, the rise in mass imprisonment demonstrates how unsuccessful this was. It was only effective in increasing rather than lowering mass imprisonment rates, resulting in hazardous neighborhoods. During Reagan’s administration, jail building also increased.

When slavery was abolished, white supremacy established new institutions such as lynching and segregation. They are all aimed against some form of racism. If we believe that racism should not be tolerated, we must abolish jails.

Rather than waiting for problems to arise, the approach is to address sociological concerns at their source. Better schools, entertainment centers, and other juvenile resources should be available in place of jails. Community activism can aid in the development of those who are not driven into a life of crime. It’s time to focus on the cause rather than the result. When slavery was abolished, white supremacy established new institutions such as lynching and segregation. They are all aimed against some form of racism. If we believe that racism should not be tolerated, we must abolish jails. Rather than waiting for problems to arise, the approach is to address sociological concerns at their source. Better schools, entertainment centers, and other juvenile resources should be available in place of jails. Community activism can aid in the development of those who are not driven into a life of crime.

It’s time to focus on the cause rather than the effect, in a world where justice equals punishment but punishment is not incarceration and is often a far reach from justice, it is time we cut off the roots, of the soon global corporation that is feeding off the innocent’s dignity and rights.