By Eirini Tassi,

“Morse code” is something that rarely rings any bell today. For the average citizen, Morse communication is usually just this cool and mystical underground sound system that you see in old war and spy movies. Upon reading this article’s title you might as well think, why am I explaining the functioning of a relatively antiquated communication system which is mostly out of use? To the surprise of many, besides the nuanced engineering of the telegraph and of the Morse alphabet itself, this coding system is essential for survival signals in various kinds of emergencies.

Some brief history

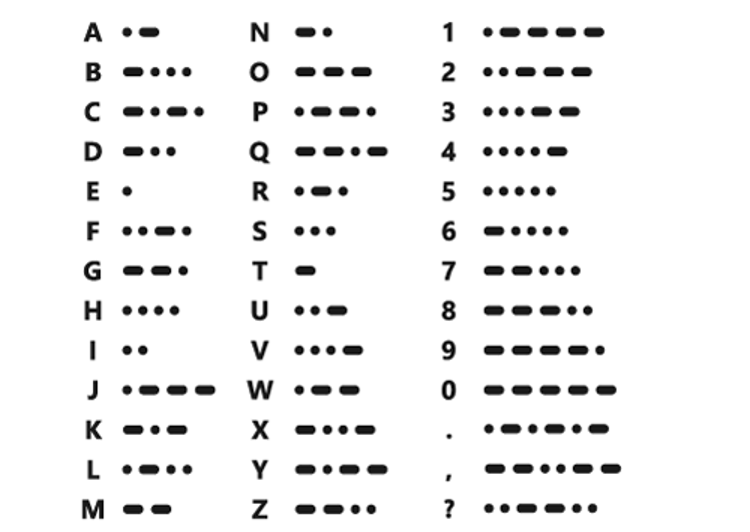

The Morse code was created in 1838 by American inventor Samuel Morse, from which it took its name. He proposed it as a customized communication method for the recently introduced electric telegraph, which transmitted long-distance messages via electric waves. In particular, he composed an austere alphabet consisting only of dots (•) and dashes (–) which in various one-to-four-digit combinations represent different letters. For example, the letter A was a dot followed by a dash (•–), while H was four consecutive dots (••••). Therefore, each dot and dash could be transmitted as a constant electric sound wave and thus effectively reach large distances.

Although not explicitly stated by Morse in his writings, it is possible that what sparked his motivation to produce a means of more instant communication was the sudden death of his first wife. In 1825, Lucretia Walker was expecting their third child in their home in Connecticut, while Morse was working in Washington. Sadly, after suffering from a heart attack during childbirth, she passed away and Morse was only able to receive this news and transport back to Connecticut after her burial, an event which he attributed to the slow, letter-based communication. It is unknown whether this incident was an actual catalyst for inventing the code, yet it is very likely that grief played a part in it.

After the 1830s, it was not long until the Morse codes’ influence spread throughout the trans-Atlantic: it became an integral tool of militaries, and navies, in particular, which often even transmitted Morse messages to bases and allied foreign ships through light signals. Its simplistic and quick transmission of information across large distances made it also particularly useful for armies involved in WWII and Cold War geopolitical conflicts (i.e. Vietnam war; the Korean War etc.). Nazi Germany, for example, encoded their messages using the program “ENIGMA” and then transmitted these modified versions to Axis commanders using Morse code. It is fascinating, but also very bizarre to think that some of the most important political and military telegraphs of the past century were communicated through dots and dashes. Today, the development of communication technologies has put the code largely out of use with Navy intelligence officers and aviators being the only actors who still use it methodically for message transmission.

While initially designed for the English language, Samuel Morse’s proposed code turned out to be largely inapplicable to other Latin-alphabet languages. It was hence revised by a collective of European officials in 1851, forming the “International Morse Code”. There, again, each letter was represented by dashes and/or dots, from one to four-digit combinations. Letters that were more frequently used in the communication received more minimal combinations to facilitate word formation, while less frequently used ones received more complex dots/dashes configurations. Hence, the letter “E” and “T”, which are the most frequently used letters in the English language, were coded by a dot (•) [E] and a dash (–) [T], whereas “L”, which was more uncommonly utilized, was coded with a dot, followed by a dash and two dots (•-••). Respectively, numbers from 0 to 9 were standardly coded in 5-digit combinations of dots in dashes in an “incremental” manner, starting from one dot and four dashes (1) and going all the way to five dashes (0).

Yet, the initial question of some still remains: why are you telling me all this? Have our technological developments not surpassed the need for such communication? Yes and no.

While there is indeed no need for Morse code and telegraphs anymore for instant, long-distance communication, there are certain circumstances of communication that technology cannot accommodate and in which the 2-digit simplicity of the Morse alphabet is particularly useful. For instance, if you end up getting lost in a large forest with no data signal in sight, your phone will be of little use. However, with the possession of a flashlight, one could signal SOS in Morse by switching it on and off in accordance with the digit configuration of each letter. Three quick consecutive on-and-off switches will represent the dots of the letter S (•••), while three longer consecutive on-and-off switches will represent the dashes of the letter O (– – –).

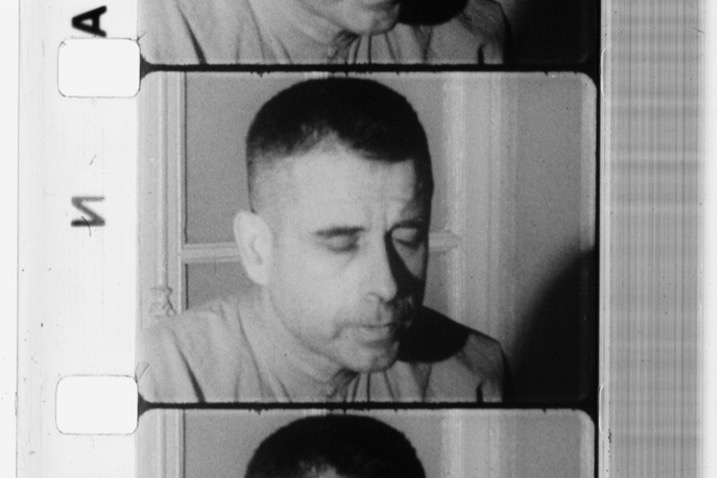

In 2017, for instance, a UK army veteran got injured upon walking on the coast of Dorset and he was found by his wife and later the authorities by signaling SOS through a simple key ring torch. But Morse code’s utility does not stop at light; message transmission could also work with so many other means of signaling, even the eyes. In 1966, US Admiral Jeremiah Denton, who was held as a war prisoner in North Vietnam, was forced to appear in a propaganda television interview in which he was to state that he received humane prison treatment, whereas in reality he was being continuously tortured. This interview was then going to be released to the world media. While complying with his captors to affirm that he was getting sufficient food and medical care, he spelled T–O–R–T–U–R–E in Morse while on screen, blinking his eyes. When the interview circulated globally, this is the first confirmation that the US Naval Intelligence ever received that US prisoners of war in Vietnam were being tortured.

While this is indeed an older empirical case, this does not stop being a relevant form of indirect communication in situations of coercion or abuse, even today. And although taken from a very brutal and disturbing example, it also shows that the simplicity of the Morse code as a two-digit communication system allows it to be adaptable to any means of communication as long as rhythm can be produced; let these be knocks, blinks, flashes – or even eyebrow raises. Therefore, while mastery of the Morse code and its interpretation is not something to be expected from the current and future “technology” generations, cultivating a basic ability in performing and identifying such survival signals is core to filling communication gaps that technology cannot fill now and that it is unlikely to fill in the future.

References

-

Army training video on Morse code. Defense, Department of the Army’s Office of the Chief Signal Officer (09/18/1947 – 02/28/1964). Youtube.com. Available here

-

Army veteran, 54, who crawled across a rocky beach for two hours after breaking his leg was saved by exchanging Morse code signals with his wife using his TORCH. Dailymail.co.uk. Available here

-

Enigma. Britannica.com. Available here

-

Gabe Bullard, The Heartbreak That May Have Inspired the Telegraph. Nationalgeographic.com. Available here

-

International Morse code overview. boxentriq.com. Available here

-

Isobel Frodsham, Morse Code. Britannica.com. Available here

-

Scenes From Hell. Archives.gov. Available here

-

The women’s auxiliary air force, 1939-1945. iwm.org.uk. Available here