By Fanis Michalakis,

The slow loris or primates in the Nycticebus genus is a cute creature with big eyes and an innocent face but also an ace up its sleeve. It is the only primate with venom. There are many questions that are unanswered but studies have given us some indication of the venom’s properties. However, before science stepped in, folklore tried to understand the phenomenon and give a “reasonable” explanation. This led to many stories involving the loris (blood or organs) that would cause death and make the ground inhospitable to plants. These stories are fun to hear but they are fascinating because they revealed that people knew about the venom but did not have the means to comprehend it or understand how it worked.

Thankfully, today we know the process’s basics and the delivery method. The venom of the slow loris is delivered through bites. Lorises and lemurs have a toothcomb, which is a dental structure formed by the incisors and the canine teeth of the lower jaw. They are typically used for grooming, since as the animal licks its fur to clean it, it can run the toothcomb to, well, comb it. However, the toothcomb in the slow loris, unintentionally, is a great way of delivering the venom, as it keeps liquids from dripping and making deep wounds on the receiver of the bite. Before they deliver the venom, they must activate it. The venom is activated by combining the oil from its brachial glands with saliva. Therefore, the loris when it feels threatened will raise its hands and lick its arm where those glands are, and the cocktail is ready. It is strong enough to cause death in small mammals and anaphylactic shock and death in humans.

Venom typically contains toxins that cause paralysis. The two kinds of paralysis can either be due to excitatory toxins that cause the muscles to contract, or depressant toxins that relax the muscles and render the animal immobile. The first kind of toxin is useful when you have to release the prey and wait for the animal to be subdued. The second kind of toxin is used by animals that save their prey for later.

There are four hypotheses for the development of venom. The first one suggests that the venom developed to kill prey. However, researchers have spent many hours observing slow lorises catching prey and there seems to be no need for venom in this function since they immediately consume their prey. They live in an arboreal habitat, so the prey would fall on the ground if it were released. Another possibility is that the slow loris got its venom to thwart potential predators. This hypothesis is also supported by the behavior of the slow loris. More specifically, in an experiment, a mother was seen covering her young with venom and leaving it. This is, apparently, a common behavior that I personally find hilarious, since they just dump their babies somewhere and return later to pick them up. The venom deters many predators, as proved by experiments in a lab, and protects the babies from parasites.

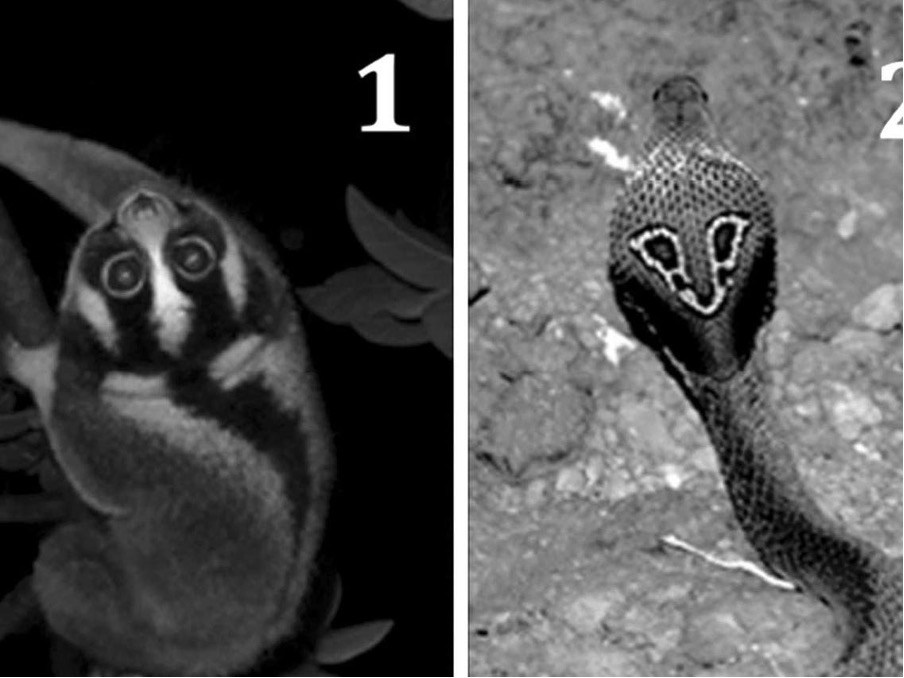

This is important because young lorises do not have an immune system that could protect them from parasites at the start of their life. Also, to remove parasites primates groom themselves. However, when the young are left alone, they have no one to groom them and slow lorises live in small groups but they can enter a period where they live alone. The third potential reason supports that the slow loris uses its venom in fights with members of its own species, especially during the mating season. There is high competition between males, and the females have territories that they share with their offspring and a few males. Protecting a territory or fighting over a female is a common sighting. The last explanation for the evolution of the venom is that it is a product of Müllerian mimicry with the cobra, meaning that it evolved to look and behave like a cobra to avoid predators without possessing the abilities of a cobra. Looking at the fur of the loris, it has a visible stripe at the back of its head and body that resembles the body of a snake and its face looks like a cobra. Sort of.

It is not necessary to be the same as the thing you want to mimic in the animal kingdom, as long as you can cast doubt on your predators regarding your nature, the animal will avoid contact, especially if you choose to look like a venomous snake.

Today, all slow loris species face extinction. Some are classified as “vulnerable”, some as “endangered” and some as “critically endangered” by IUCN and in all of them, the population is on the decline. The major threat is “hunting and trapping terrestrial animals” with “intentional use”, meaning that they are being hunted and targeted specifically. There are countless videos that show slow lorises as pets. However, since they have venom, to protect the owner, they have their teeth cut off even pulled out. In many of the videos, as people try to pet them, you can see the loris take a defensive position, which looks like a dog asking for belly rubs, but in reality, the animal fears for its life, as it does not know that we mean no harm.

They also do not function well in captivity, since they are nocturnal (so the time spent with them is minimal), require specific diets that many owners do not follow, resulting in death due to nutrition, can easily be infected and there are cases where individuals have died due to blood loss.

There are efforts made to protect the slow loris species. There are areas that are declared as “protected” where any activity involving the animals is prohibited, except for research and study with permission. There are also campaigns to combat the decrease in population due to illegal trade and many educational programs. However, some of those programs are not systematic and there is a need for field guides for rescue centers there are areas where the slow loris lives are not protected yet.

References

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- Mad, bad and dangerous to know: the biochemistry, ecology and evolution of slow loris venom. scielo.br. Available here