By Maria Koulourioti,

New year same old goals concerning lifelong cultural affairs. Following a publication by Britain’s Daily Telegraph on the 6th of January, long-term objectives concerning Greece’s cultural integration are bound to remain elusive dreams, as British officials use the term “cultural exchange” to embellish the ugly truth. Thus, the incitement of the customs, history, and ideas of a people to an ignominious business, while turning a blind eye to a past of colonialism, and cultural and humanitarian exploitation.

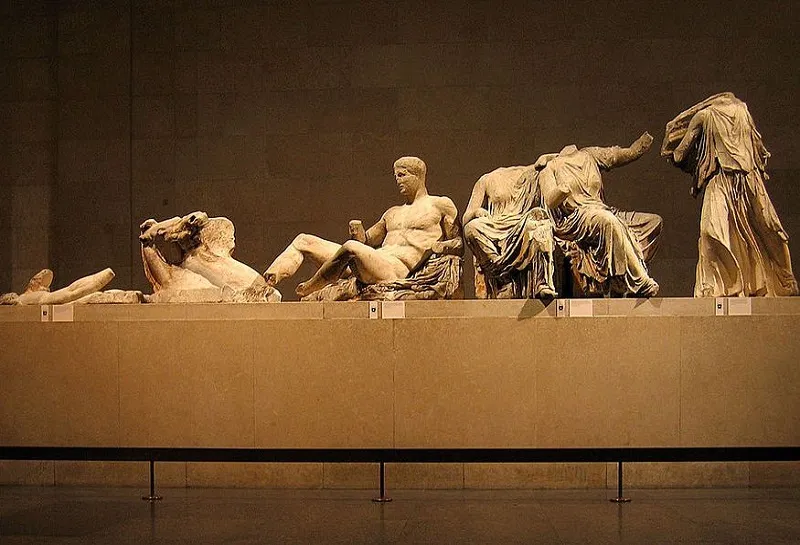

Particularly, the British Museum referred to “constructive discussions” with Greece over the Parthenon sculptures, meaning whether the 2,500-year-old statues ought to be returned. On the other hand, Greece has repeatedly called for the permanent restoration of the sculptures ever since British colonial administrator Lord Elgin removed them from the Parthenon temple in Athens in the early 19th century, when he was ambassador to the Ottoman Empire then ruling Greece.

The Greek government said last month it was in talks over their repatriation and Telegraph reported that an agreement had been drawn up between the museum’s chairman, former finance minister George Osborne, to allow them to be returned as part of an “exchange deal”. The paper reported such an arrangement, which would in effect be a loan arrangement, could be resolved in time. Nonetheless, Greek officials stated that discussions were at a precursory point.

“We have said publicly, we are actively seeking a new Parthenon partnership with our friends in Greece and as we enter a new year constructive discussions are ongoing,” the British Museum revealed in a statement. Other artifacts could also be shipped out on loan, with Greece prepared to offer highlights of the collection of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens to sweeten any deal for some of the Elgin Marbles. Stars of the National Archaeological Museum collection could be offered on loan in exchange, including the circa 150 BC Jockey of Artemision, a 10-foot-long bronze statue of a thoroughbred being ridden at speed by a small boy, who once would have held decorative reins.

As predicted, the proposed exchange deal is relatively unlikely to conclude the diplomatic row over this reunification, as Greece ought to campaign for a full transfer of ownership of the Elgin Marbles, something the British Museum claims that is unable to offer under UK law. Another stumbling rock is the need to delineate specific concepts, as British Museum refers to all its loaning artifacts as legally owned, while Greece is up for defamation. Furthermore, the British Museum states that any deal tabled by Mr. Osborne would need to be a bespoke agreement, which suggests that Greece has to recognize the “legal” claim of the artifacts and monuments, but historical events have indicated that no concrete solution to this problem has yet been found. The Department of Digital Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) has said that it does not intend to push any legislative change to amend the British museum act of 1963, a legal barrier that prevents the British Museum from simply giving away or “deaccessioning” objects in its collection.

The Parthenon Sculptures are only an integral part of that story and a vital element in this interconnected “world collection”, as mentioned on the official site of the British museum. Following Dan Will’s exhibition, Ugly Truths was purposefully curated to start a conversation regarding British colonial history. They achieved this through the lens of one of Britain’s most expensive and bloodiest colonial conflicts: the South African War (1899-1902), also known as the Second Boer War. Africa had been invaded and settled by Europeans around 500 years ago.

At the conflict’s conclusion, returning service people brought back numerous objects from southern Africa to Cornwall. Eventually, they would become part of the Royal Cornwall Museum’s collection. For example, the yataghan bayonet and scabbard were taken from the battlegrounds of the conflict of the dead body of a Boer soldier. This is an object with a morbid and morally challenging past. It was likely stolen as a trophy of the conflict; to commemorate and glorify combat experience and success.

What occurs when a big part of your country’s cultural treasures and heritage are “owned” by another country that illegally obtained them? Nigeria, for instance, had been invaded by the British in 1897. Over a century later, surviving bronzes are on display at museums in the United Kingdom and other countries but not in Nigeria, their country of origin. Moreover, the 2018 film Black Panther addressed the issue during a heist scene set in the fictional “Museum of Great Britain”, where characters reclaimed stolen artifacts from the also fictional African country of Wakanda.

In the end, where are these endless and ineffective democratic dialogues that opt to connect culture and business in the same sentence leading us? It is widely known that the pressure to restore the stolen, sometimes referred to as legally obtained artifacts will continue. So far, international attempts have not achieved much significant difference. The question we must find a solution to is not who owns history, but how we make ourselves capable of reversing it.

References

- Wills, D. (2022) Collections, colonialism, and the ugly truths of our past. royalcornwallmuseum.com.uk. Available here

- Little, B. (2019) British Museum is ‘world’s largest receiver of stolen property’. independent.co.uk. Available here

- Simpson, C. (no date) Elgin marbles could be swapped for 2,000-year-old bronze statue of jockey. msn.com. Available here

- The parthenon sculptures. britishmuseum.org. Available here