By Erika Koutroumpa,

The Atacama desert in South Chile is the driest non-polar desert in the world. With it extending from the Andes to the Pacific Ocean, the water sources of the region have been long under dispute. The most recent resolution to one of those came earlier this month, on December 1st, with Chile and Bolivia finally agreeing on the future of the Silala River with the help of the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Before the dispute is discussed, one needs to understand the significance of the region in Latin American economy and politics. The Atacama desert was the source of Chile’s wealth until World War I thanks to nitrate deposits and ports, playing an essential role in the country boasting a world monopoly on Nitrate. In addition to the mines, the region has really proven to be Amalphia’s horn thanks to the limited farming activity that also takes place in the area (lemon, potato, alfalfa which is a type of hay). A vast area of the desert originally belonged to Bolivia and Peru, but Chile managed to dominate the area due to mining industry interests. The final nail to the coffin, ensuring Chile’s geopolitical dominance was the treaty of Ancon (1883) after Chile emerged victorious from the War of the Pacific (1879-83).

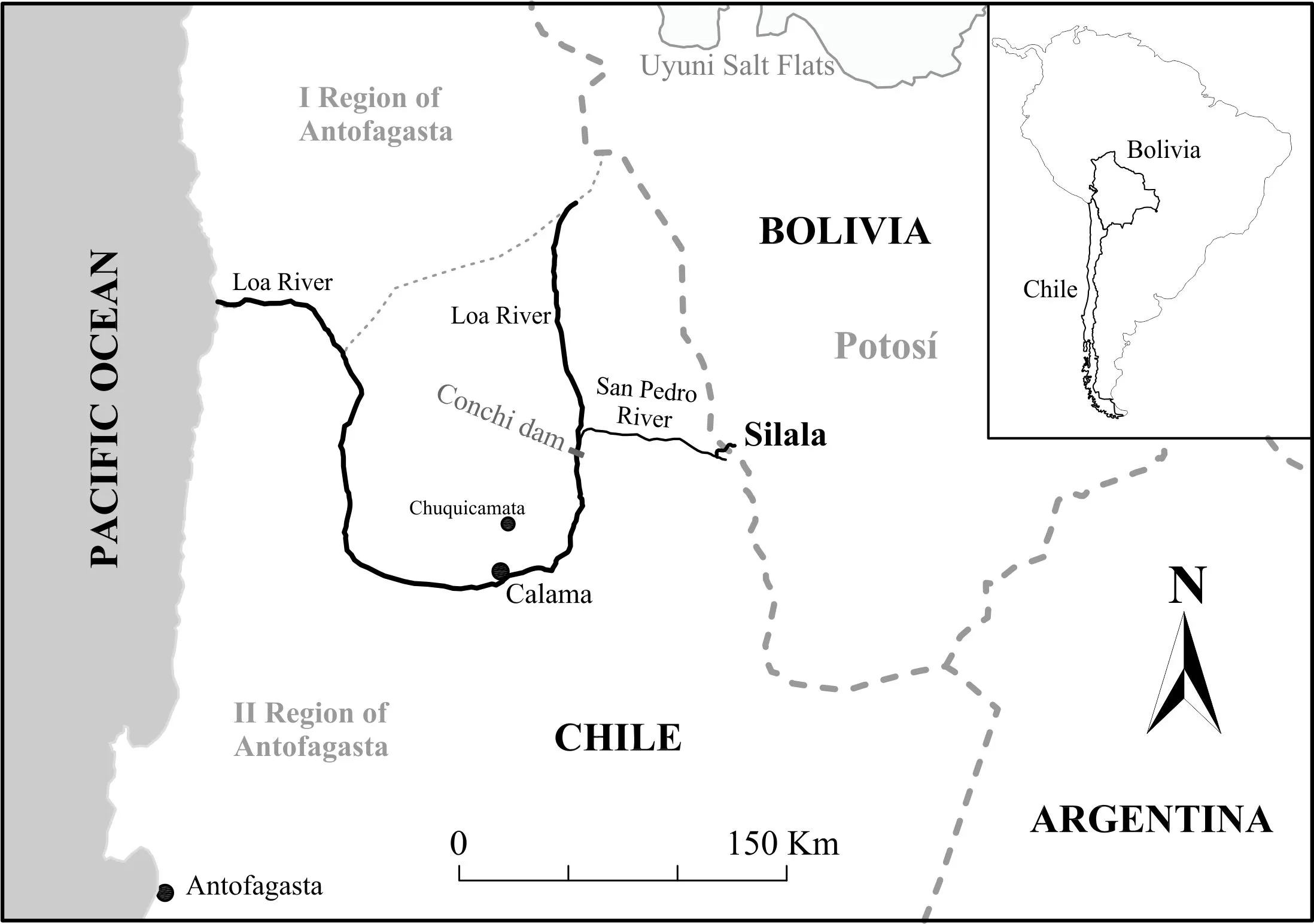

Before the war of the Pacific, Bolivia had exclusive ownership over the Silala basin, which then turned into shared ownership. The Silala river waters originate from groundwater springs in the Sur Lipez province of Bolivia and according to some historical evidence, the river used to flow between both countries. But that was until 1908 when the Antofagasta and Bolivia company (Chilean company with headquarters in both Chile and Bolivia) got approval from the Bolivian region department to construct canals in Bolivia to redirect the watercourse towards Chilean territory before finally emptying into the Pacific Ocean in order for it to power its steam engines. But when the company switched to diesel engines in 1961, the canals were still in place despite having served their purpose. The company also got a concession to supply the city of Antofagasta with drinkable water, building canals for what they claimed were sanitary reasons.

Meanwhile, the waters of the Silala river intertwine with those of the Loa river and are put through a variety of uses by Chile, most significantly Chuquicamata river copper mines, some of the largest open pit mines in the world. This led to Bolivia claiming that Chile built channels in order to redirect the river and increase the surface flow of the river to Chile, with the 1908 concession finally being revoked in 1997. By 1999, the Bolivian government had put the Silala river waters out for public tender. Bolivian company DUCTEC took up the task but failed miserably at getting any money back from FCAB or the Chilean National Copper Corporation, and hence the contract ended in 2003 on grounds of non-performance.

Later, in 2004, cooperation efforts between Bolivia and Chile began for the first time through a bilateral group, which failed at resolving the problem and was terminated after a few meetings. Around this point in time, the two stances towards the river were formed: Chile claimed that it was an international river and hence they had the right to equitable use of its waters, and on the other hand Bolivia supported that the watercourse was exclusively theirs, requesting money from Chile as compensation for years when the river was used to generate locomotive power.

The case had been building up for years, however, it was only brought forth back in 2016, with Chile making a plea to gain legal certainty over their right to use the waters. This move mostly stems from Chile’s insecurity over water scarcity in the country. At the same time, on October 2018 landlocked Bolivia has gone to court and requested a license from Chile to give them a corridor of water to utilize, which was rejected. For the vast majority of the trial, a question that needed to be resolved was whether the body of water can even be considered a river. Chile supported it was indeed a river, while Bolivia counterargued that it was merely wetlands that Chile manipulated via the creation of canals, increasing the water flow. The main legislation related to the dispute was the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, a treaty that neither of the two countries has ratified.

Before the highly anticipated December 1st verdict, it was expected that the Silala river case would make a precedent for international water source disputes. Due to climate change and the diminishing water sources in the world, more cases like the one on hand were expected to arise, highlighting the importance of a court decision on the matter. Much to everyone’s surprise, though, there was no actual verdict. Both parties agreed on the Silala river being an international watercourse and have decided that moving forward, they will make equitable and reasonable use of the Silala river. This ruling comes at a time when both countries are in a tough position due to diminishing freshwater sources, and during the worst drought in 47 years for Bolivia’s wetlands.

With the river officially being considered an international watercourse, it will be under customary international law rules such as the obligation to cooperate and distribute resources fairly and not to cause harm. The two countries will have also to disclose information, consult and negotiate with each other before taking action that will impact one another. This also means that over-utilizing or diverting the river will be considered illegal, which could potentially be a reason for dispute in the future. Many would consider the decade-long dispute over the use of Silala river’s waters settled by now, however, this could be just the beginning of a new trend of international court cases as water sources on the planet become scarcer by the day. This was just one of the first missed opportunities to create the precedent needed to adjudicate future disputes. Sooner or later, the international community will have to reach a consensus over rules and regulations for water sources before the number of disputes increases.

References

- Andean Water Wars: the Silala River case, Ronald Bruce St John, Council on Hemispheric affairs, 5 August 2019. coha.org. Available here

- The Silala Dispute: Between International Water Law and the Human Right to Water. qil-qdi.org. Available here

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Atacama Desert”. britannica.com. Available here

- ICJ declines to issue decision in Chile-Bolivia water dispute. aljazeera.com. Available here