By Irene Tassi,

Admittedly, the environment had not really been an issue of political concern throughout most of the past century. This makes sense if you recall the multilateral geopolitical tensions and ideological clashes that the world was involved in. The 1970s, however, changed that, with the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment marking the starting point of global environmental politics (UN). Since then, the “climate talk” has taken a prominent place in the political arena: governments are increasingly subjecting intrastate production and consumption to anti–pollution regulations and various global climate regimes, like the Kyoto Protocol and its successor, the Paris Accords, have emerged in an effort to limit human–induced global warming (UN). The Paris Agreement, in particular, aims to limit systemic rising temperatures at 1.5 °C compared to pre–industrial levels (UNFCCC). It urges governments to diminish fossil–fuel energy usage, limit excess food production and most importantly, decrease greenhouse–gas emissions by implementing stricter sustainability regulations on intrastate producers (Cornwall 2020).

That was a solid plan by the Agreement’s policy designers, and it seems to have already triggered some change: across Europe, greenhouse–gas emissions are 23% lower than those in 1990 and the Climate Action Tracker predicts that temperatures will rise to around 2.9 °C by 2100, compared to 3.5 °C if the Paris Accords were not implemented (UNFCCC). There is still a far way to go through. While significant, this change is not substantial enough to address the urgency of global warming. Rising sea levels due to melting glaciers are already threatening Polynesian states like Tuvalu and are worsening natural and humanitarian disasters like this year’s floods in Pakistan.

These are two of many empirical manifestations of global warming, signaling that we should be doing more and faster. It is difficult to do that through climate regimes like the Paris Agreement, as their non–binding structure prevents them from pragmatically pushing governments to limit their greenhouse–gas emissions. But the problem goes beyond government power too. Even when governments wish to implement sustainable reforms, they face a colossal and almost undefeatable force: transnational corporations.

According to Clark and Klin (2013), only around 90 multinational companies are the emitters of two-thirds of global greenhouse gases (Giacomini and Turner 2015). And yet, almost any government regulation to restrict such activities appears to leave them intact. I would thus argue that while we should investigate ways of making the Paris Accords more binding, our bigger focus should be on decreasing greenhouse-gas emissions through the multinational producers directly.

How can transnational corporations resist anti–pollution regulation by the government?

The interstate activity of TNCs along with their colossal net revenues are two concrete elements that allow them to bypass pollution standards.

To begin with, such companies usually have their headquarters in developed states with strong regulatory frameworks but then their factories of production in developing states lack strong environmental regulations or an effective judiciary. This allows them to usually escape state fines, trials and other such legal restrictions and to continue to pollute indefinitely. Yusuf and Omoteso (2015) explicate this problem through the case of Nigeria, where the inefficiency of regulatory bodies to restrict unsustainable pollution in the oil and gas market, allows industry giants like Chevron and Shell to pollute extensively and continuously.

Furthermore, even if such states attempt to strengthen their environmental legislation vis–à–vis TNC pollution, such companies can block its implementation by threatening to pull investment out of that country. Nigeria, for instance, introduced a new anti–pollution production policy in 2008, and in response, Shell and Chevron threatened to withdraw a 50–billion–USD investment in the country’s oil industry if the bill gets put into force. This thus gives TNCs massive bargaining power (i.e. “the upper hand”) in determining how flexible pollution regulations will be (compared to the governments of developing states) since the national economy’s fate is usually in their hands (Yusuf and Omoteso 2015).

This is less likely to happen in developed and especially liberal democratic states, where strict regulatory pollution frameworks are much more binding to TNCs. But even there, multinational corporations can usually find ways to still stay one step ahead. Even if they do become subject to fines, or trial settlements the amount of money they would have to pay as compensation to the government, the local community, or another related institution is usually an unsubstantial burden to their colossal profits and thus does not really push them to reform their production. For example, the Taiwanese Formosa Plastics Corporation, which systemically damaged the ecosystem of a small Texan town in which one of their plants was operating, had to pay a settlement of 50 million as ruled by a US court (Fernández 2019). This seems like a very large amount of money –and it is– but how burdening is it actually to Formosa, whose annual net income revenue is at around 7–9 billion USD?

This goes to show that both in developing and developed regulatory frameworks, TNCs are able to cleverly utilize institutions, investments, and profits to their advantage and continue their pollution unbothered.

What would be a solution?

Based on the above inability of state and global–regime actors to regulate TNC polluting–production activities, a more substantial way to demand they limit their environmental damage is through non-violent civil disobedience (direct action). This includes blockades, trespassing, demonstrations, boycotting and other such methods directed towards big–polluter corporations with no substantive environmental standards in place (Sovacool and Dunlap 2022: 3). Boycotts, in particular, allow consumers to collectively refuse to spend money on the products of big–polluter corporations and to thus push them to adopt more sustainable production methods (Pezzullo 2011). This “push” is much more pragmatic than government regulations because such protest techniques essentially hurt a company’s absolute tool of survival: profit.

In particular, transnational corporations are interlinked in global oligopolistic networks, which makes profit maximization essential in maintaining their market share and remaining in the market. And, while loss from government pollution fines can be overcompensated by their colossal profits, a revenue loss from decreased consumer demand for their products cannot do so as much. Therefore, if consumers abstain from purchasing a specific company’s products methodically and prolongedly, this will lead to long–term diminishing demand for the firm’s goods and services and respectively, to revenue decline and even exit from the market. Such firms are thus much more likely to comply with consumer pressure and in turn regulate their pollution, to protect their survival.

While I understand that this consumer scenario might sound a bit too optimistic, there are prominent empirical cases that prove that this works. Notably, the boycott of Mitsubishi for its environmentally damaging activity resulted in a sustainable reform of production corporate practices in two of the company’s branches. Furthermore, the boycott of Mt. Olive Pickle Company which was launched US–wide by the Farm Labour Organising Committee pressured the company to reform its supply chain in a way that substantially benefited sustainable production and social equity. These are two of several cases of consumer–based pressure on giant oligopoly polluters.

Even in sectors or markets where concerted boycotts have not taken place, companies increasingly indicate their fear of their consumer demand falling because they adopt strategies of corporate social responsibility (Audrain et al.: 2020). That is, the “self–regulating business model that helps a company be socially accountable to itself, its stakeholders, and the public (Fernando 2022). This means that, in recognizing that consumers are now more environmentally conscious and that they pay much closer attention to the degree to which firms employ ethical practices of production, they are pushed to adopt sustainable reform in fear of losing consumers, and in effect, profits (Audrain et al.: 2020 and Russel et al.: 2016). This essentially shows that their driving force for resorting to more environmentally friendly production methods is to maintain their customer base. Therefore, if we wish to pragmatically push for more environmentally conscious production from transnational corporations, altering their products’ demand by refusing to consume them (i.e. boycott) is our most solid starting point.

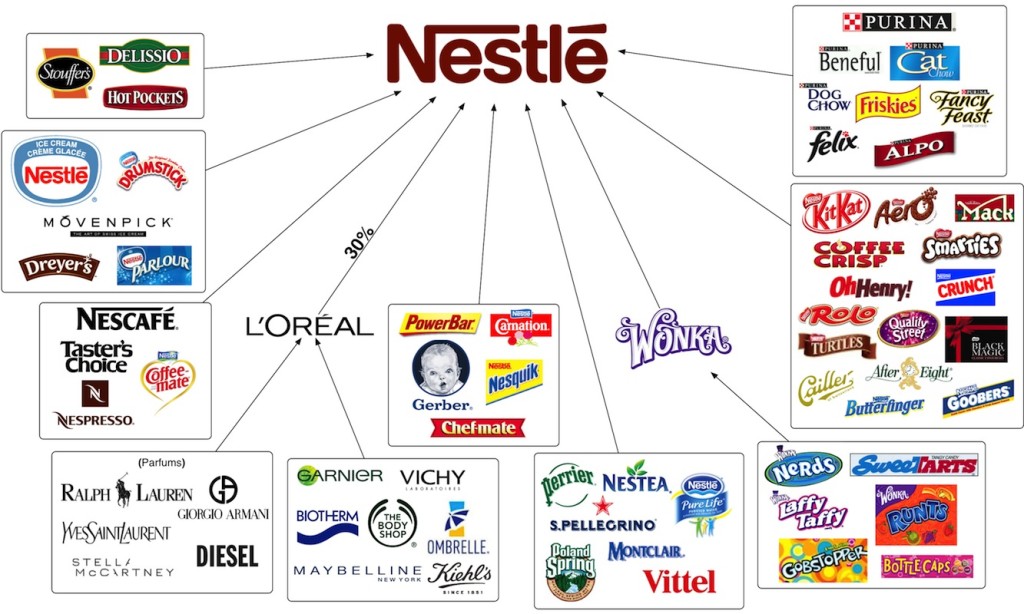

This does not come without limitations, though. Some goods and services rarely have substitutes, like energy commodities such as gas and electricity, and others that do, usually all belong to brands that are owned by two-to-three global oligopolistic players. Nestlé, for example, which is the modern blueprint of unethical and exploitative production, owns most brands of wheat and oat-based goods, which are all integral nutritious products for a lot of consumers (Nestlé). This makes boycotting relatively unsubstantial in that respect. The options here would be to either redirect consumer demand to that oligopolist’s global competitor (who also owns a substantive amount of other such brands) or to concentrate the direct-action effort in relatively more fragmented oligopolistic markets.

Overall, every possible solution vis–à–vis global warming should be taken with appropriate scrutiny, with regard to different stakeholders, and with the environmental future being one of our utmost priorities. Using our consumer power to condition transnational corporations’ pollution practices is a solid starting point, as consumer demand is a large determinant of oligopolies’ profits. Transnational firms are very aware of that, hence why they pursue corporate-social-responsibility reform to maintain their customer base. Manufacturing giants like Mitsubishi also confirm this, as they performed sustainable production reform in response to a heavy boycott. Our next steps should be to empirically examine the conditions and exact strategies that can lead to successful environmental boycotts, but also, what actors/institutions can more effectively mobilize them. Could it be possible, for example, to use interstate boycotts to condition TNCs within the framework of a more binding, reformed global climate regime? Whatever we do, “later” is not the time, and leaving TNCs out of the equation is not the solution either. In the end, if we do not manage to stop this sustained rise of greenhouse gases in the next decades, our expiration date is much closer than we imagine.

References

-

Audrain-Pontevia, A.F., Durif, F., and Zeng, Tian. (2020). “Does corporate social responsibility affect consumer boycotts? A cost-benefit approach”, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management.

-

Dunlap, A., and Sovacool, B.K. (2022). “Anarchy, war, or revolt? Radical perspectives for climate protection, insurgency and civil disobedience in a low-carbon era”, Energy Research & Social Science, 86: 1-17.

-

Russell, C.A., Russell, D.W. and Honea, H. (2016). “Corporate Social Responsibility Failures: How do Consumers Respond to Corporate Violations of Implied Social Contracts?, J Bus Ethics, 759–773.

- Omoteso, K., and Yusuf, H. (2015). “Accountability of transnational corporations in the developing world. The case for an enforceable international mechanism”, Critical Perspectives on International Business, 13:1, 54-71.

- Pezzullo, P.C. (2011). “Contextualizing Boycotts and Buycotts: The Impure Politics of Consumer-Based Advocacy in an Age of Global Ecological Crises, Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies”, 8:2, 124-145.