By Katerina Dimarogkona,

Who would have imagined that the word “natural” would be so divisive? It is a weapon word that is routinely used to describe “unnatural” everything; from technological innovation, to birth control, to homosexual identities. People seem to conveniently call them “natural” and find the rest an abomination of nature. In Natural: How Faith in Nature’s Goodness Leads to Harmful Fads, Unjust Laws, and Bad Science, Alan Levinovitz examines the word’s usage in a variety of circumstances, including childbirth, sports, farming, grocery stores, national parks, and many more. It is a term with several meanings that are applied differently depending on the circumstance.

Since Levinovitz is a religious educator, it stands to reason that most of the debate he uncovers is related to religion. It has tainted our perceptions, perverted our reasoning, and implanted irrational prejudices that seem impossible to eradicate. He finds it often promulgates ignorance, despite facts available. The enormously silly and tortured arguments over what constitutes natural sexual practices (and therefore not birth control) are a classic example.

There is a significant effort to revert to natural birthing practices. This is due to how sophisticated the medical system is, which allows us to support these love experiments. The state of relative cleanliness, the availability of help, and the research available make all the difference in the world. In the same way, ancient diets are often not the best way to get nutrients, and an effort to return to natural habitats for people who have gotten used to cities often results in injury or death.

In the evolutionary biology of childbirth, “nature” is a stand-in for what is sometimes referred to as the “[…] environment of evolutionary adaptedness (EEA). Originally coined in 1969 by the psychiatrist John Bowlby, the concept is fairly straightforward. All species, including humans, are the products of evolutionary adaptation to a certain kind of environment. Remove a species from that environment and you might see biological dysfunction or ‘evolutionary mismatch'”.

So, according to people like Levinovitz, this idea of the natural exists and is useful in this sense of evolutionary mismatch. In humans, evolutionary mismatch has been plausibly blamed for everything, from rising obesity rates (we evolved in an environment where calories were not plentiful) to allergies (artificially hygienic environments are changing our microbiome and causing autoimmune disorders). This would be the cause for things like minor gynecological diseases and back problems that are now more common than ever due to our “unnatural” way of living, which does not match the environment in which we initially adopted.

On the other hand, Yuval Noah Harari, an acclaimed writer and historian, in a recent debate claimed that natural and unnatural is a useless binary. Everything that exists is natural. The unnatural, he says, is that which does not exist because it violates the laws of nature. We create, for example, computers from materials that are found in nature, we ourselves are a part of nature, so in this sense, something like a computer is no less natural than something an animal makes, like a bird’s nest.

But is the claim that some things are more natural than others a useless distinction? The thing is, we as people do not defend our natural state just because we think it is good. That would be simplistic, but the argument is more complex. It is good not because it does not kill you, but because it results in a stable equilibrium. Natural things are those that have survived the test of time. The things we humans create have not been tested enough. They might be good, bad, life-saving, or grotesque, it does not matter. Almost all intentional human achievement presents itself as an improvement on nature and it certainly is. In the short-term.

The thing we do not know about what we create is if the implications and the side effects it has on us will backfire and kill us. Even the best of human ingenuity is a gamble in the long term, because of our deep lack of understanding of nature’s inner long-term stability, and its self-recreating cycles. The environment is more significant than ourselves, it is bigger, older, and more complicated than we could imagine, and the idea of naturalness is nothing short of calling out the absurdity of trying to play god with an environment that has had delicate balances for millions of years, with surface level logic.

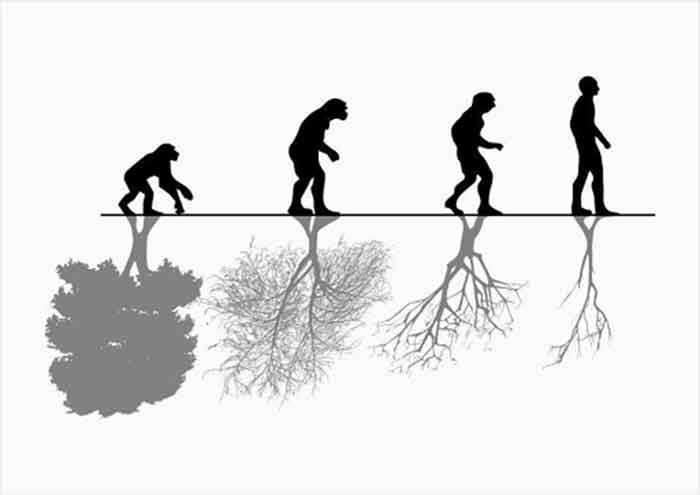

The fear of the unnatural is the fear that we do not really know what we are doing with anything in the long term. People do not revere nature because we think it is better. We prefer it because they recognize that nature is vast and that we do not understand it and certainly cannot easily improve it and expect not to meddle with the balance it has had forever. We recognize that an attempt at improving our conditions should be a humble attempt, a quiet and slow one, done cautiously. The binary between natural and unnatural things is often taunted as foolish because of our human arrogance. We think that as apes that have not been conscious for more than 10,000 years, we can redesign the very environment that created us.

Levinovitz counsels a nuanced view of nature and what is “natural”. “No foundational principles about Nature’s law predetermine your position on genetically modifying babies or proper sexual habits. The default is uncertainty, ambiguity, and openness to complexity and change”, he continues. When considering “nature”, we need a combination of faith, science, and wisdom. Be suspicious of any claims of nature because we do not have a good definition of what that is. Being natural means different things to different people.

The rate of change in things is the problem. The rate at which we change everything is much faster than nature would change on its own. And that means that we do not have time to test the consequences of our actions as they ripple through the whole system. And the thing is, you just cannot predict the consequences of change this big. It is not possible to design another state of such a stable balance. It is not possible to act as humans have been acting and to do that responsibly. The truth is we do not know what we are doing.

References

- Alan Levinovitz, Natural: How Faith in Nature’s Goodness Leads to Harmful Fads, Unjust Laws, and Bad Science, Beacon Press, 2020

- AI will deepen divisions, say Yuval Noah Harari and Slavoj Zizek, theweek.co.uk, Available here