By Katya Mavrelli,

While we argue that History often repeats itself, suggesting that there is a common trajectory in everything and that international relations are being based upon predetermined models, that is not always the case. If History did indeed repeat itself, it would suggest that we as humans are not of the progressive type – that we do not learn from our mistakes, as if we live in a loop.

And, while this is not always the case, there are exceptions. The Ukraine-Russia crisis is one of them.

The scene of international relations nowadays might resemble a movie: the threat of war is palpable, diplomacy is not even considered as a “plan B”, and world leaders implement strategic but unidimensional decision making. It feels like a scene from the past, from the period of the Cold War, where big power rivalries were all anyone could think of as if they were the most significant thing around which everything revolved – society, politics, economics, culture, education.

For more than 40 years, from 1947 until 1991, the US-USSR rivalry created a tense, but stable equilibrium, and competed along with different domains. But after the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US was the only power standing. The defeat of communism meant the triumph of capitalism, democracy as perceived along western lines, liberalism, and market openness – and this remained the status quo for another long period. The unipolar world that emerged and the subsequent world order that presided over everything was not contested: the international community embraced the idea of the all-knowing, powerful, and unchallenged US, bilateral relations were designed along these lines and institutions of international security, cooperation, and economic were based on this idea.

The hegemon of this world order remained uncontested, until relatively recently. While the biggest challenger was always thought to be China, since it aggressively – yet at the same time subtly – wishes to remove the US from its leading position in international affairs, Russia and Iran are following closely. And from these two, the Russians are the ones to look out for.

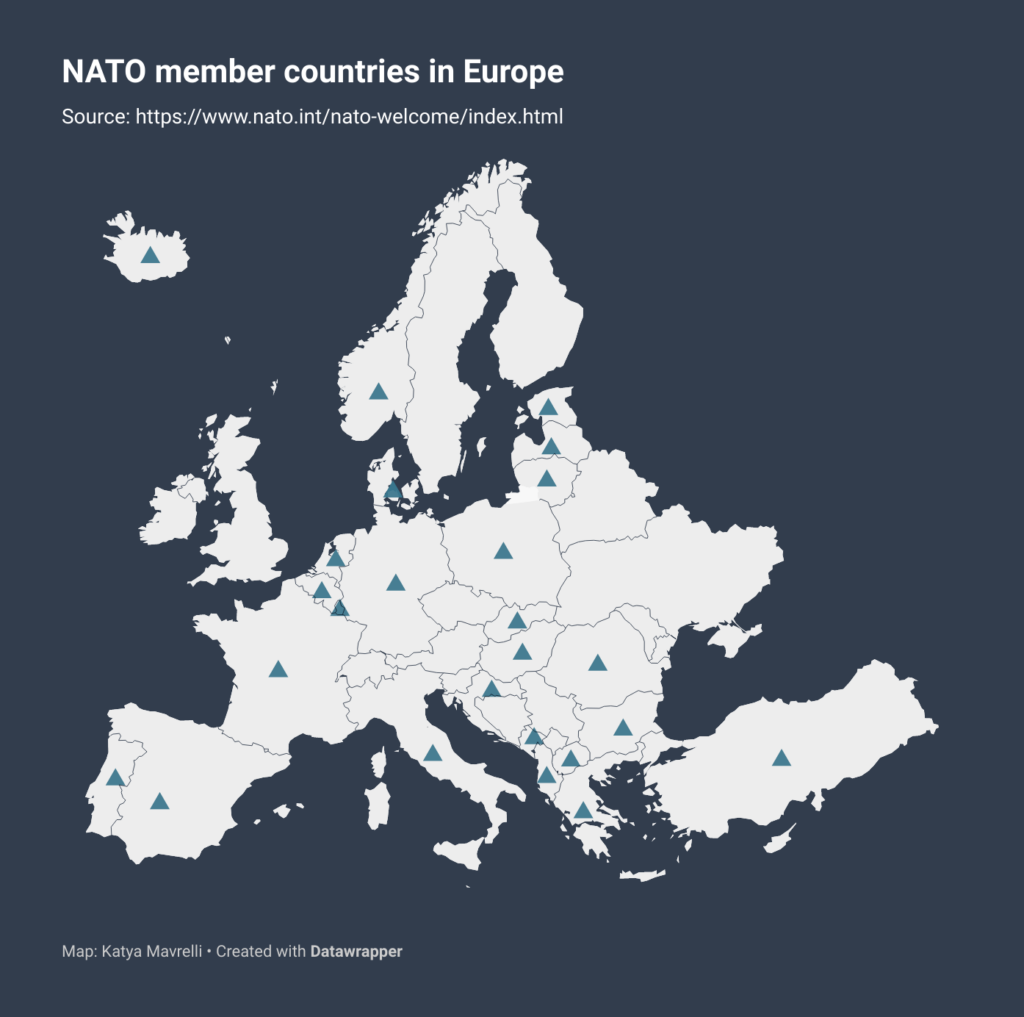

In an attempt to bring back the evaporated glory of the Russian empire and cement the Putin legacy, the Kremlin is preparing for war in an intense and coordinated fashion. The conflict will determine not only the future of Ukraine, but also the way we perceive energy, the importance of natural resources in covering energy demands, and the role of international security institutions like NATO, for geopolitical stability. In his attempt to prevent any possibility of encirclement, Putin presented US President Biden with a list of demands, requesting that NATO stops its expansion to the east, prevent Ukraine’s membership in the organization, and overall avoid turning the status quo against Russia.

But where does Turkey fit in this equation? How did Erdoğan’s focus shift from the region of the eastern Mediterranean to the wintery Russian scenery? There can be two explanations for this, one seemingly simplistic, though central to the region, and another more strategic one.

Is it about economics?

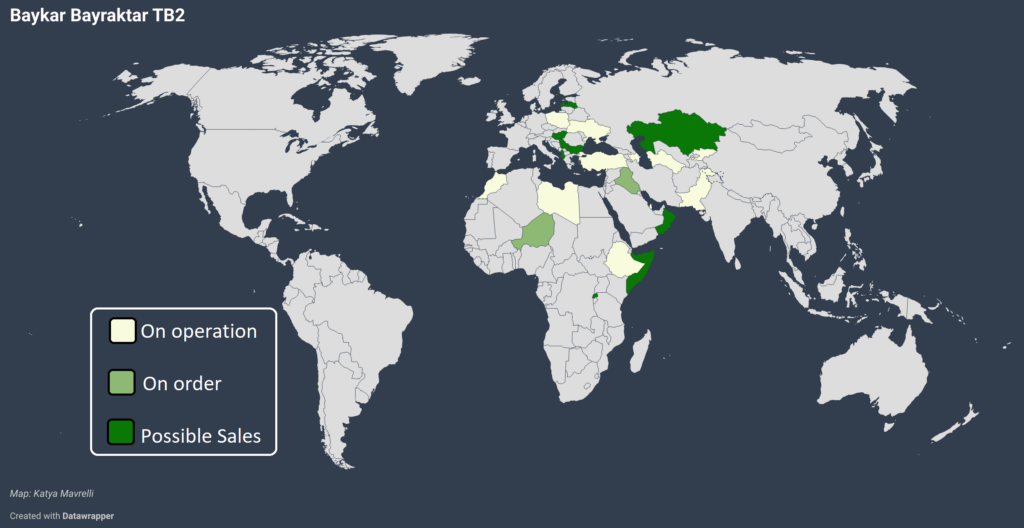

Turkey and Ukraine signed a free-trade agreement in early February, in an attempt to strengthen the economic linkages between the two and support the defense industry. With this in mind, Erdoğan is trying to establish a Turkish defense industry that will specialize in foreign markets, in order to acquire technology and knowledge and better protect the Turkish state. Receiving the backing of the west also helps Erdoğan paint a different image of his government abroad: the Turkish drone sales to Ukraine are perceived as a move of NATO solidarity, united against Russian aggression.

The cooperation also matters for Ukraine, which perceives Ankara’s decision to back this partnership as an extension of a lifeline, especially since NATO membership remains a distant idea. Allying itself more strategically and more closely to another NATO member, Ukraine takes another step in the direction of ensuring the backing of the west. For countries that are on the margin, not exactly in an international security organization, but also not quite out of it, strategic “friendships” with other big countries may be the key for their survival.

The partnership comes at a critical time for Turkish politics as well, with the Turkish lira performing daily summersaults and the national economy becoming more and more unpredictable every day. With this partnership, Erdoğan successfully distracts the Turkish population, making people look at the bigger picture, instead of focusing domestically. Diversionary tactics like these ensure that developments that may be unfavorable for the continuation and future of the AKP government are being swept under the carpet, and issues that are global in nature acquire a more central stage.

Maybe it is about ideology?

Even though the economic story is a very persuasive one, the political interpretation of the involvement in the crisis in Ukraine is a bit more telling.

In an attempt to extend the Turkish influence subtly, Erdoğan is becoming more and more involved internationally. With his recent visits to neighboring countries and his efforts to foster deeper ties with old friends, Erdoğan aims to prove that Turkish leadership is far from unimportant for international developments. Undoubtedly, Turkey’s involvement in Libya and Syria has unsettled the status quo, but the efforts to get closer to regional states aim to show that Turkey is better for more than just dismantling the existing world order – it might be able to paint one of its own.

The desire to mediate the crisis between Ukraine and Russia also stems from the fact that Erdoğan wants to make Turkey contemporary, to turn Turkey into a country of the present, and to eliminate the idea of a failed empire of the past. The revival of the glory of the Ottoman empire underlines every political decision that the current government has made, since the 2002 general election victory for AKP, but the troubled past is an element that Erdoğan has set out to redefine.

Turkish foreign policy is defined by two key elements: decisiveness and flexibility. Powerful decisions are being made within a matter of hours, and political maneuverings allow the prevention of large-scale conflict emergence. Despite the aggressive rhetoric and the provocative nature, strategic decisions are being made on several fronts. The Ukraine front is a key one, given that any disruption in the stability of the region of the Black Sea would have large-scale implications for the greater eastern Europe.

The desire to mediate in the crisis is also fueled by the “zero problems with neighbors” doctrine, which underlines the strategic importance of regional cooperation and the prevention of unnecessary challenges. Erdoğan is trying to mend as many friendships in the region as he can, build as many new ties as he can, and create as many bridges with the west as possible.

His desire to get involved in Ukraine is not to meddle in the affairs of the east, or to attempt to compete with Putin for regional hegemony – it is to foster strategic relations that may prove to be useful in the future.

The security balance in the region is hanging – quite literally – by a thread. Abrupt movements and sudden changes will upset the status quo and will change the existing delicate equilibrium. This is not something that leaders prefer, and it is why Erdoğan is swooping in to save whatever he can.

Even though he took decisions in unorthodox ways, differently from how the West would have done, Erdoğan managed to subtly get involved in the situation without favoring one side and upsetting the other. Even though the cooperation is more centered around economics, with diplomacy and security being variables that have not yet entered the equation, the current equilibrium lasts. Ankara did what the west was unwilling – or unable – to do, and this salvaged the current standing of things.

Sooner or later, more direct measures might be necessary, but for now, the duct tape that has been placed to mend international stability manages to hold things together.

References

- Monday Briefing: Turkey and Ukraine ramp up defense cooperation, mei.edu, Available here

- Can Turkey’s Erdogan mediate a deal between Russia and Ukraine?, dw.com, Available here

- The Russia-Ukraine crisis, explained, vox.com, Available here