By Socratis Santik Oglou,

In 1922, the Union of Arts and Industries was founded in Chicago with the aim of promoting and implementing “good” design in the country, which would allow it to compete with European products. The Union hoped to establish a school for designers capable and suitable for industrial production. Arrangements with the School of the Institute of Art did not work and some of the members of the Union of Arts and Industries turned to the Bauhaus as a model for what a design school should be.

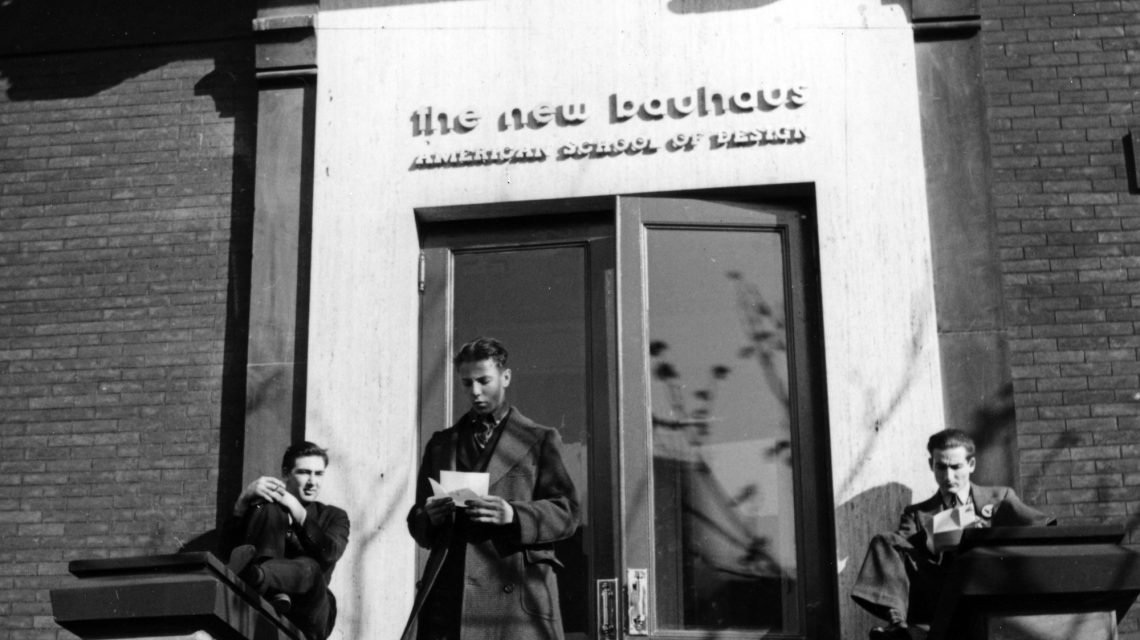

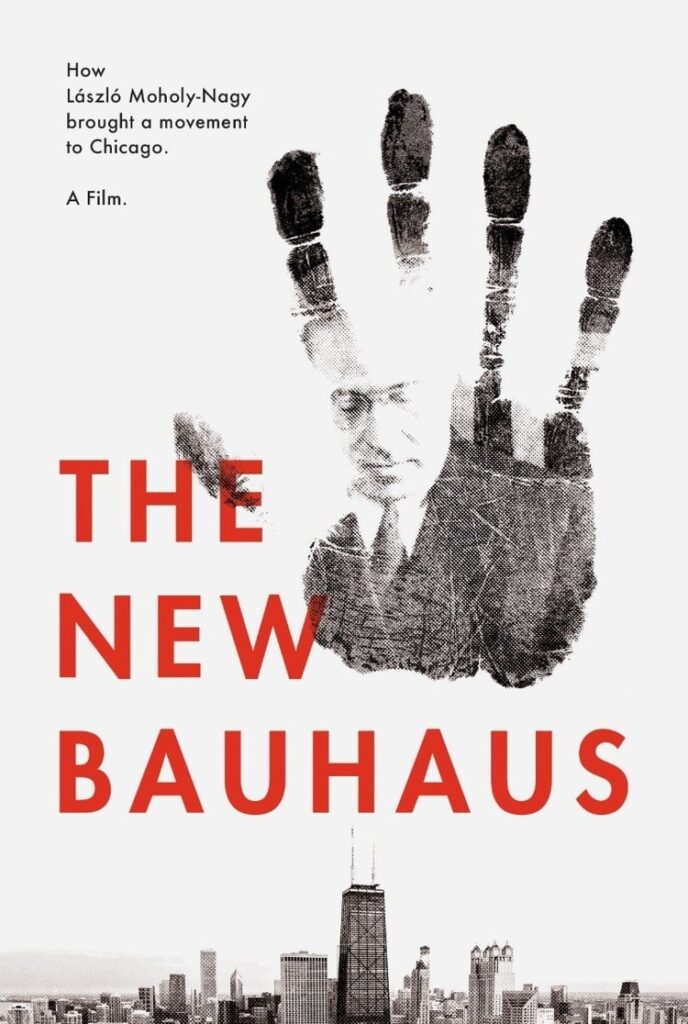

In 1937, the Union invited Walter Gropius to run this new school in Chicago, but Gropius had already accepted a position at Harvard University, but recommended one of his closest associates in the Bauhaus, László Moholy-Nagy. Moholi-Nagy accepted the position of director and so, on October 19, 1937, he began the operation of “The New Bauhaus: American School of Design”, based in “Victorian Castle” on the Field.

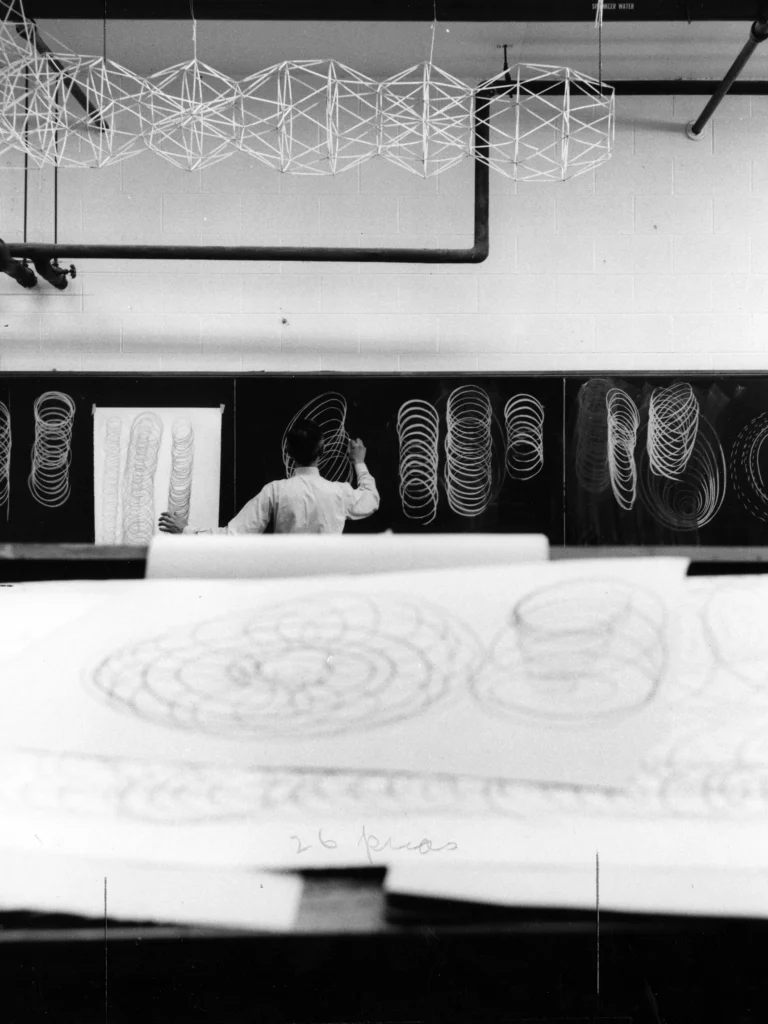

The curriculum was based on that of the German Bauhaus, with the introduction of certain academic classes taught by professors from the University of Chicago. Students to obtain their degree would have to attend five semesters in the workshops, with the first two courses focusing strictly on the exploration of materials and shapes in order to produce artists “conscious in volume and space”. The method applied to the school was a philosophy of creative freedom, which was translated into a very informative educational experience.

The cost of attendance per semester was only $150, moreover, accepting Moholi-Nagy’s philosophy of capitalism, the original teaching staff did not deliver grades at the end of the semester.

As the teacher described in his posthumously published book Vision in Motion: “This school advocated the experimentation and teaching of the entire student, a spiritual descendant of the original concept of the “total work of art” of the Bauhaus”. This method followed in the workshops, gave students exposure to cutting-edge materials and mentalities, and offered a grounding for future product designers.

Vision in Motion presented extensive photographs of student projects, all extremely modern while showing little easily distinguishable industrial functionality. The first student exhibition was filled with abstract creations. Clarence Bouliet, the art critic at the Chicago Daily News, said the “gadgets” had “no useful purpose”, while another critical view described the report as “exposing bewildered anonymous objects”.

In the autumn of 1938, due to economic problems, they led the Union to leave the New Bauhaus, and thus, it was permanently closed.

Onto the Masters of the Bauhaus from Germany to teaching in the U.S.A.: Walter Gropius, Josef Albers, and Mies van der Rohe

One of the most important architects of the 20th century is Walter Gropius (1883-1969). He was one of the founders of Modernism and founder of the Bauhaus. With the founding of the Bauhaus, Gropius was able to convey his various ideas to reality. The innovation in his educational methodology lays in the practical training in the workshops, which operated with a Master of Works and an artist (master of form). The most important period of work for the Bauhaus is considered to be that in the city of Dessau, where Gropius, as mentioned in the first chapter, designed the school building but also the residences of the teachers (1925-1926), the Dessau-Törten residential estate (1926-1928) and the Employment Office.

In 1934, after the final closure of the school by Hitler’s government, Gropius and his second wife, Ise Frank, left Germany for England. England’s stay was marked by his collaboration with architect Maxwell Fry at Village College in Impington, Cambridgeshire, in 1936.

In February 1937, Gropius arrived in the U.S. to teach in the department of architecture at Harvard University. The following year he became chairman of the department, a position he held until his retirement, in 1952. There, he introduced the Bauhaus’s philosophy into the curriculum, although practical abolition in the laboratories was not possible. His ideologies of modern design immediately became popular among his students. His didactics and the innovations he introduced at Harvard led to the reorganization of other architectural schools in the U.S.

From 1937 to 1940, Gropius worked with Marcel Breuer, his former partner in the Bauhaus. Among their plans was Gropius’ house in Lincoln, Massachusetts, while at the same time their plans were considered controversial. In 1942, Gropius renewed his interest in architecture when he became Vice President of the General Panel Corporation, a company that built prefabricated houses.

In 1946, in collaboration with six of his graduate students at Harvard, Gropius formed The Architects Collaborative (TAC), based in Cambridge. Among its varied American and international committees, TAC likewise designed and constructed the Harvard Graduate Studies Center (1949-50), student dormitories, and dining rooms. Their design is reminiscent of the Bauhaus Gropius building in Dessau. Other TAC plans include the U.S. Embassy in Athens (1960) and Baghdad University. Gropius remained an active member of the TAC until his death, in 1969.

After the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933, Josef Albers and his wife immigrated to the U.S. At the suggestion of the Museum of Modern Art, he was appointed to a position at Black Mountain College in Ashville, North Carolina. Black Mountain College was a small community, a school of general studies and not art as many believed, of course, this fact is due to the teaching of Albers there. A central element of his teaching, which was based on the Bauhaus philosophy, was the teaching of perception, the relationships between the elements, the combination of the behavior of the elements with the behavior of people, while he developed the characteristic concept of “respect” for the other color, material or shape.

The principles of the Bauhaus, of “practice before theory”, of “learning by practice” and of “studying, not of art”, were mutilated and applied there by Albers. His didactics were essentially aimed at acquiring the perception of behavior, balance, analogy, and art relationships that could be applied to individual human life, while these kinds of lessons about life became more and more important as the years passed in school for Alberts, because, he argued that a healthy education meant learning to balance respect for other people with the obligation to think about himself. Ethics also occupied an important place in his ideology-philosophy, while another perception he wanted to pass on to his students was that art is an experience and not a commodity.

Moreover, because of this ideal character of the college and its financial problems, Albers took advantage of every means while encouraging improvisation and experimentation. The lack of degrees, the principle of college, also encouraged freedom and experimentation. His lessons attracted young artists, such as Willem de Kooning.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) was already a bright star of German avant-garde architecture when he joined the Bauhaus as its director. A year earlier, his architectural plans for the impressive Barcelona Pavilion successfully represented the achievements of the Weimar Republic at the World’s Fair in the Spanish metropolis.

The Bauhaus, as mentioned in chapter one, closed in 1932, but Mies tried to continue the work of the school as a private institution, based in a telephone factory in Berlin, called the “Independent Institute of Teaching and Research”. However, the country’s new national socialist government eventually caused the institution to capitulate. Mies decided not to reopen the school. Thus, on August 10, 1933, the Bauhaus was permanently closed for Germany.

In 1938 the Armor Institute of Technology, a technical training school on the south side of Chicago, hired the German architect as a principal in the department of architecture. The Institute aimed to transform its architecture program into a program of international prestige and innovation that could compete with the European schools. Mies was a reasonable choice to achieve this goal since he already had international recognition in modern architecture and gained a reputation in the field of education during his years at the Bauhaus.

After relocating to Chicago in 1938, Mies reformed the school’s architectural education and developed a disciplined curriculum to be held in an environment of collaboration. The curriculum included progressive lessons, inspired by the Bauhaus, on the visual and tentative characteristics of materials, as well as fundamental classes on design and manufacturing techniques. The students began their training with the methods and materials of architecture to provide them with a sound basis for future studies. Only when the students had fully acquired the understanding of the basic concepts could they proceed with the construction of buildings.

Mies saw architecture as an incarnation with multiple levels of value, extending from the fully functional to the realm of pure art. He also believed that his goal is to truly represent his time and that the architect should seek and articulate the importance of the time.

The Bauhaus, despite its brief operation, undoubtedly left its mark on modern and postmodern architecture, art, and design at an international level. It was there that the foundations of modern mass industrial production were laid. Indeed, one can easily observe that the ideas of the school are applied until today, simply by observing the mass-produced objects of his home, but also the products of the popular furniture companies. Most curricula nowadays, both of architecture and applied arts, are based on the methodology and philosophy applied there, while at the same time, the products designed and manufactured in the Bauhaus, both by teachers and students, are today collectibles, while many are produced and used en masse in our everyday life.

References

- Federick A. Horowitz, What Josef Albers Taught at Black Mountain College, and What Black Mountain College Taught Albers, blackmountainstudiesjournal, Available here

- Harvard years of Walter Gropius, britannica, Available here

- Institute of Design: A Brief History, moholy-nagy, Available here

- Mies van der Rohe, arch.iit, Available here

- The New Bauhaus, a radical design school before its time, archive.curbed, Available here