By Katya Mavrelli,

In the last decade, an increasingly frequent topic of discussion has been the topic about Turkish foreign policy. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has time and again maneuvered his way through international developments and has put Turkey under the spotlight. Aiming to make Turkey a regionally steady political and economic power, Erdogan has been pursuing a “zero problems” policy, which has left both him and his country with no friends. How did the flagship policy of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) lead to this unpredictability? Can Ankara survive this long-term crisis? And will Erdogan emerge gloriously victorious or significantly defeated from this turbulence?

Just 10 years ago, Turkish foreign relations and their role in the eastern Mediterranean area and the Middle East looked significantly different when compared to today’s disarray. The economy was growing at an increasing rate, with high levels of GDP growth and the undertaking of several projects, and the Turkish lira was increasingly confident and stable as a currency. The new government was beginning to play an important role in the region, with prospects of becoming an emerging regional power that could positively shape the Middle East.

The scene changed when Ahmet Davutoglu’s foreign policy of “Zero Problems with the Neighbors” was implemented in February 2004. For decades, the cultivation and maintenance of good neighborly relations had been at the top of the agenda of many governments in Turkey, but Davutoglu’s new plan made the minimization of enemies and the increase in friendships lie at the epicenter of political decisions of the new AKP government. The plan was simple: Ankara would steadily become the mediator in important Middle East and eastern Mediterranean decision-making and would cultivate peaceful relations with the West. This policy brought Erdogan under scrutiny by the international community, which was now observing the leader with the Islamist credentials even more closely than before.

Ambitious though this plan was, Erdogan found himself facing a Gordian knot just a few years after the policy came into force. The ideology and the results of this policy failed to come to some alignment, leading to today’s complex Turkish foreign policy and turbulent international relations. Despite the steady improvements in relations with Syria and Iran in the first half of the 2000s, these results have long been forgotten and replaced by the continuous challenge that Turkey now poses to the West, with its flamboyant rhetoric and challenging prose.

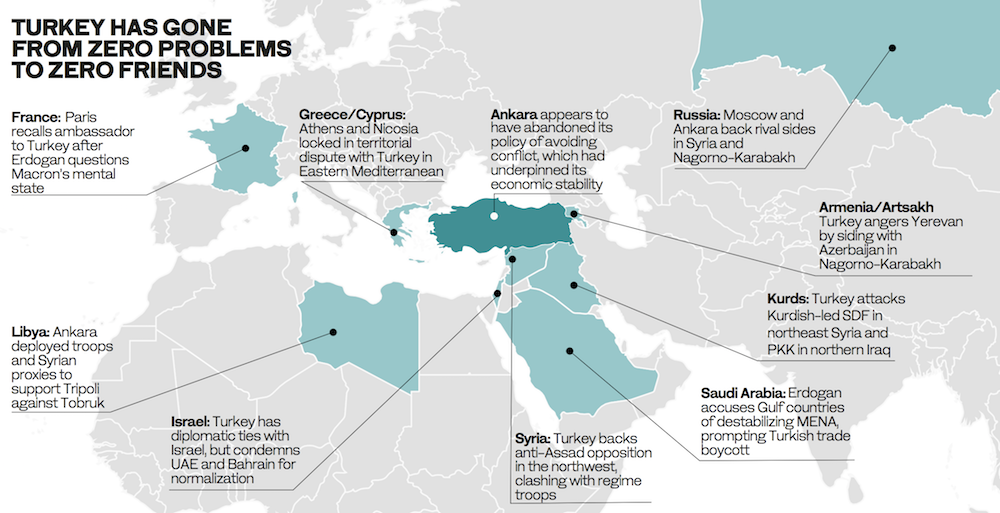

In just 10 years, Turkey went from “zero problems” to “zero friends”, being left virtually alone as a consequence of its overambitious and provocative foreign policy stance. Naval drills in the Mediterranean have seen French, Greek and Cypriot authorities in tense standoffs with Turkish ones. The historic competition against Greece and Cyprus has intensified in the last 5 years, with Turkey resembling a hawk flying over the eastern Mediterranean, challenging the established status quo and questioning the sovereignty of negotiated agreements, such as the Treaty of the Sevres and the Treaty of Lausanne. Looking towards its Middle Eastern neighbors has done Turkey no good either, coming into conflict with Israel and Egypt over maritime sovereignty as well. The former has also added Turkey in its list of annual threat assessments for the first time, which signifies that bilateral relations have deteriorated significantly. Peace talks with the Kurds have also been replaced by hostilities and the worsening of Ankara’s relations with Iraqi Kurds. Several Arab states started boycotting Turkish goods with hashtags on social media platforms encouraging this informal initiative. And of course, the involvement in Syria’s civil war and in Libya can not go unmentioned, with Erdogan striving to adopt a leading role in each conflict.

It all boils down to Erdogan’s ultimate aim of bringing politics and religion into line by combining religious rhetoric with political aspirations and by eradicating the long-established Kemalist secular sentiment to replace it with a more firmly stabilized religious outlook. Turkey’s use of religion as a political tool in order to rally support has raised red flags internationally, with its agenda becoming an ever more important issue of international discussion. Turkey has entered a revisionist phase, one which has been ongoing since the emergence of the AKP, which dictates the course of the country in the international sphere and challenges not only the existing world order but the future as well.

More recently, Turkey turned its attention deeper into Europe, coming into an unexpected clash with France for the first time. In a standoff that could be defined by boisterous challenges and superficial threats, Erdogan seized the opportunity to disguise himself as the ‘defender of Islam’, just like the Caliphs of the bygone Ottoman Empire. Revivifying the glory of the six-century-old empire requires meticulous attentions, strategy and planning, all of which have been pursued for the past decade under the current regime.

So how did Turkey go from “zero problems” with neighboring states to a situation where it is left virtually alone in the international arena?

It goes without saying that the more a nation grows in terms of muscle power, the more it will clash with its neighbors. No one likes the redefinition of the status quo and most rational-thinking leaders will put a lot of effort to prevent the situation from turning against them. But with Turkey, this increase in muscle power has been steady for the past decade and up until now few have been the ones that have stood against it, trying to prevent the further increase of its regional influence or attempting to halt its hegemonic ambitions internationally.

The case for Turkey could be successfully portrayed as a close interplay between strategic decisions, personal aspirations and beneficial political maneuverings. However, another main driver behind this turbulent political orientation has been the economy. Despite providing his people with some successive years of growth and progress, the economy has now entered the dark tunnel of recession, with no exit in sight. To name just one example of this game of distractions, this was the case with Erdogan’s declaration of support for the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt after the beginning of the Arab Spring in 2011. Casting himself as the “protector of Islam” could serve Erdogan no better than distracting domestic attention from the worsening economy and his own increasing authoritarianism. These two pivots, once combined with personal hegemonic aspirations, lie at the epicenter of Turkish foreign policy.

And though this might seem like a simplified version of reality, the heavily wounded economy in Erdogan’s battlefield against domestic instability and loss of support may serve as the shield he needed to hold on to power for as long as he can master. Every challenge that has been issued against neighboring Greece or Cyprus or taunting Germany and France, have served him well, as they allow him to convey a determined image at home, to expand his hegemonic desires and to bring uncertainty towards his regime to its knees.

The problem, however, is that this continuous entanglement abroad, with the issuing of challenges here and there, will ultimately be the undoing of Erdogan, who has already started losing a lot of support. And despite him trying to overcome these impediments, by silencing national media outlets and imprisoning opponents like the determined Canan Kaftancioglu, his future seems less stable. His international focus has been to drain resources which has shifted focus from domestic matters that constitute his main source of support. And if he does not satisfy this support threshold, he will have to kiss his legacy goodbye, because the public will either blame Erdogan openly and seek another leader or Turkey will become the next pariah state, left isolated from its Muslim neighbors, its fellow Mediterranean powers and from the West.

In the recent decade, it has therefore become evident that Erdogan has turned from another elected leader of the newly-formed AKP, promising progress, modernization and development, into a modern sultan, a caliph if you want, wishing to broaden his support base and achieve ambitiously hegemonic goals. Western analysts describe how morally wrong these moves are, yet for a long time they served him well, allowing him to consolidate his power and strengthen Turkey both at home and abroad. Yet if you zoom out of this concept, you see a state that is becoming increasingly weakened and, as a result, even more aggressive in its settlements or demands. In these years, ‘diplomacy’ has become an unknown word in Erdogan’s dictionary, leaving a hole where previously rationalized plans of action had been.

Turkey has waltzed through inconsistent foreign policies, none of which has been solidified enough to allow analysts to lay down a precise and consistent path. From the low intensity turbulences created under the Kemalist state, to the “zero problems with neighbors” dogma under Davutoglu to the current model of “problems with everyone, neighbors or not, and zero friends”, Erdogan has unsettled the groundwork and has drained Turkish stability.

One thing is certain: the new geopolitical focus, with its hegemonic ambitions, its clashing settlements and its Islamic aspirations, has transformed Turkey to its core. And the implication? There is no direct prediction for the future, given that instability has prevailed. But the pursuing of this treacherous path will signal the end of the Erdogan regime, rather sooner than later.

References

- Trading economics, Turkish Lira. Available here.

- Kathimerini, Turkey eyes undoing of international treaties. Available here.

- Deutsche Welle, Egypt’s leadership feels markedly threatened by Turkey. Available here.

- Deutsche Welle, The french turkish spat that-could widen the civilizational divide. Available here.

- Reuters.com, Saudi retail chains join growing informal boycott of Turkish products. Available here.

- Atalayar.com, Erdogan’s model continues to lose public support in Turkey. Available here.

- Foreign Policy, A Motorcycle-Riding Leftist Feminist Is Coming for Erdogan. Available here.