By Mado Gianni,

“What have we been doing our whole lives?”, wonders Petar’s sister a little while before she dies. Petar does not reply. Not in this instant. Not ever throughout his life. It is a wonder if he ever thinks about that at all.

The 61st Thessaloniki International Film Festival has been taking place online since last Thursday (5/11) and so far, one of the films that has definitely stood out is February by Kamen Kalev. The film competes in the Balkan Survey category of the Festival and it is a Bulgarian production written and directed by Kalev.

Kalev takes us into the journey of Petar’s life from when he was a little boy, through his marriage and military years and up until the last years of his life. The film is divided into three parts which undoubtedly makes one feel like living through eternity. It is extremely easy to lose interest in the film which I am guilty to admit I almost did. Watching Petar and his grandpa waking up every morning only to follow a similar routine; herding the sheep, taking naps under trees, cooking some food on the stove, eating the food that they cooked, sleeping, and sometimes even exploring the surrounding area. From the perspective of a 6-year old, discovering the ghosts of the old house up in the hill can be kind of a big deal. Yet, the story never progresses towards that direction. We are back at the farm with the sheep more often than not, observing the two sleeping, eating and herding.

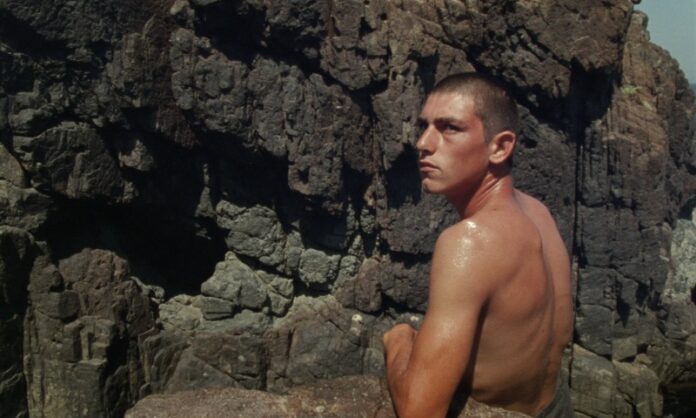

Part II. Petar, a man of 18 years old, is undergoing preparations for his wedding. A whole lot of observing again. The women who sing traditional songs for the bride-to-be while she is getting ready. The wedding, the food, the dancing, the smiling and all the celebrations and traditions that come with such an event. The eye of the camera is only recording the events as they happen creating a certain poeticism, albeit bordering boredom again. Petar leaves for the military. He is sent out to an island; he serves his time and is eventually asked to stay on and become an army official. Some could see it as the turning point of the film and also Petar’s big break. He refuses. End of story. Again, there is no indulging into an abruptive change of events. We are just left wondering where life is going to lead Petar from here onwards.

Part III. Petar is 82 years old. Kalev has spared us most of Petar’s life. The old man is living in the mountain working in the farm by himself. Sometimes he goes out to hunt for birds or other animals. He walks a lot; he harvests the land and he cooks. Throughout the film, we observe the boy, the man and the elder from up close but we rarely hear him speak. As an elder man, he often talks to his sister on the telephone. This is the first and only time, the viewer is exposed to Petar’s feelings. His sister is telling him to stop working and to go back to the village because she is dying. He tells her he is going back when the season is over and asks of her to wait for him before she dies. In the end, his sister dies and he arrives just on time for the funeral.

Through his filmmaking, Kalev explores the interaction of human and nature to a considerable extent activating the viewer’s soft spots for the search of meaning. The director also includes a voice-over narration, making it unclear if it is Petar the one who is speaking. Are we witnessing his thoughts or is this an outside narrator? In a very memorable moment, the voice-over indulges into an explanation which reads along the lines of, “I do not know of the word sin. For I would have to have lived in order to have sinned.” It would be close to impossible for Petar to have such conscious depth of character, therefore, we can safely assume that it is Kalev’s auteurism which finds its way through the voice-over. Similar to the likes of Jean Luc Godard in the French Nouvelle Vague period or Terrence Malick in the modern American cinematic era and many more auteurs, Kalev has created a piece of modern cinema heritage.

February particularly speaks to the times we are living through, indirectly addressing the timely issues of both the health and climate crises that the world is faced with; the isolation, all the tangible or intangible restrictions we have to set, the attempt of keeping our personal relationships intact through this change of the way of life that we used to know; and the uncertainty of the future. Petar lives one life and he lives through it without ambition or regret, only duty. A tailor-made duty that Petar himself has had the liberty to define -to some extent, within the boundaries of his destiny.

Throughout the whole film, I was waiting for the inexplicable to happen. And yet, there it had been all along. This film is not a ghost story, or a romance gone wrong; it is not a thriller or a piece of philosophy. February’s narrative is timeless and the film is the better version of a filmic experience. Contrary to what most would think, this is not a film about the futility and mundanity of life. Quite the opposite, it is a film about self-knowledge, inner peace and the beauty of life in whatever form it comes. Inspired by his own grandfather, Kalev tells the story of a past generation. And if they did it, so can we.