By Theofanis Fousekis,

From the beginning of humanity, people have had the natural urge to speak, communicate and express their needs and feelings towards one another. Progressively, they reached their goal. In the very beginning, humans produced sounds in order to communicate. Five thousand years later, people are talking fluently using words and, even frequently, using only emojis. The story of people having the urge to communicate, is the story of women in the rural Chinese province of Hunan.

The year is 1910. We are in Jiangyong Country in the province of Hunan in southern China. The government does not allow women to be educated with only some exceptions of aristocrats. On the contrary, women help in the fields, abide by wicked traditions such as foot binding and their names do not appear in written documentation of genealogy. It is logical that under these circumstances, women of lower levels in society needed a way to satisfy their urge to communicate like the first humans on the earth once wanted. And this is exactly what they achieved.

The province itself presents a foggy, dramatic scenery covered in sandstone peaks, a deeply incised river valley and rice paddy fields. The area in general is mountainous, with many hillside hamlets. Within this wonder of nature, Nüshu is born: the only writing system in the world created and used only by women.

女书 or Nüshu literally means “women’s script”. The exact chronology that the language may have been invented is unknown. Researchers speculate that the language was used after 900 A.D. Many of its characters have been used informally in Chinese since the Song and Yuan dynasty around the 14th century. The use of Nüshu reached its peak during the reign of the Qing dynasty from 1644 up to 1911. It was mainly used as a form of expression that many women had been deprived of at the time. Usually, the script was passed down from peasant mothers to their daughters and it was practiced among women in the community.

During the Qing dynasty only 2 to 10 women knew how to read and write Nüshu as most of them were living in big city centers such as Beijing. Alas, women in Jiangyong would only practice copying the script as they saw it. Even so, this simple practice gave rise to a unique feminine culture that still exists today. The language remained a secret gem buried deep in the mountainous Hunan province until 1983 when a report concerning the language was submitted to the central government. Before that, the language went though a progressive decrease in use as younger girls had less access to Chinese literacy, and altogether with its suppression during the Japanese invasion (1930s-1940s) and China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), the language fell to disuse. The last known fluent speaker passed away in 2004.

Even though the events that the world has lived through since the dawn of 2020 have changed many aspects of society as we know it, this specific language is experiencing something of a rebirth. Today, the language has been transferred in a nearby small river island under the name of Puwei. In 2006, three scripts found in Puwei were listed as National Intangible Cultural Heritage by the State Council of China. A year later, a museum was built on Puwei Island. There, a team of interpreters and so-called “inheritors” of the language learned how to read, write, sing and embroider Nüshu.

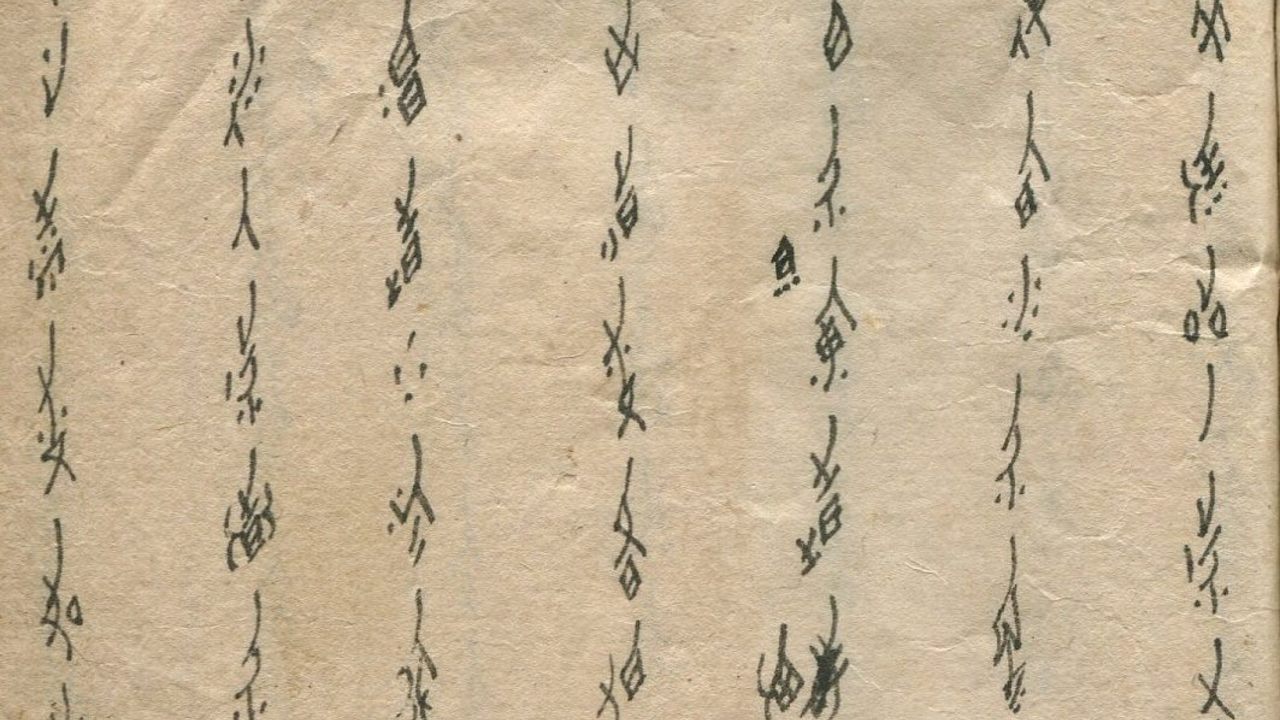

Nüshu, although it is referred to as a language, it is more of a script as its name suggests. Like all other Chinese characters, Nüshu’s syllables are written in columns with characters running from top to bottom in each column and with all columns being written and read from the right to the left. Approximately, there are 1.500 characters in the script, including variants for the same pronunciation and function. In-between the scripts, researchers found out that there are about 550 distinct characters in the script. Usually, Chinese characters are ideograms which means that one symbol represents a whole word. Nüshu characters, on the other hand, are mostly phonograms which means that they represent sounds with some ideograms. Using a sharpened bamboo stick and makeshift ink from the burnt remains left in a wok, women across the rural Jiangyong region tried to cope with domestic and social exclusion, while keeping tight bonds with people from nearby villages.

As the script was only practiced in writing, there was not any official way to speak it. Yet, when women gathered together they usually sang songs or poems on the topic of birthday wishes or marital complaints. Thus, during these gatherings and while using this script, women tried to share their experiences with the younger ones, teach them to respect and how to be good wives in order to prepare them for the hardships they would face in the future.

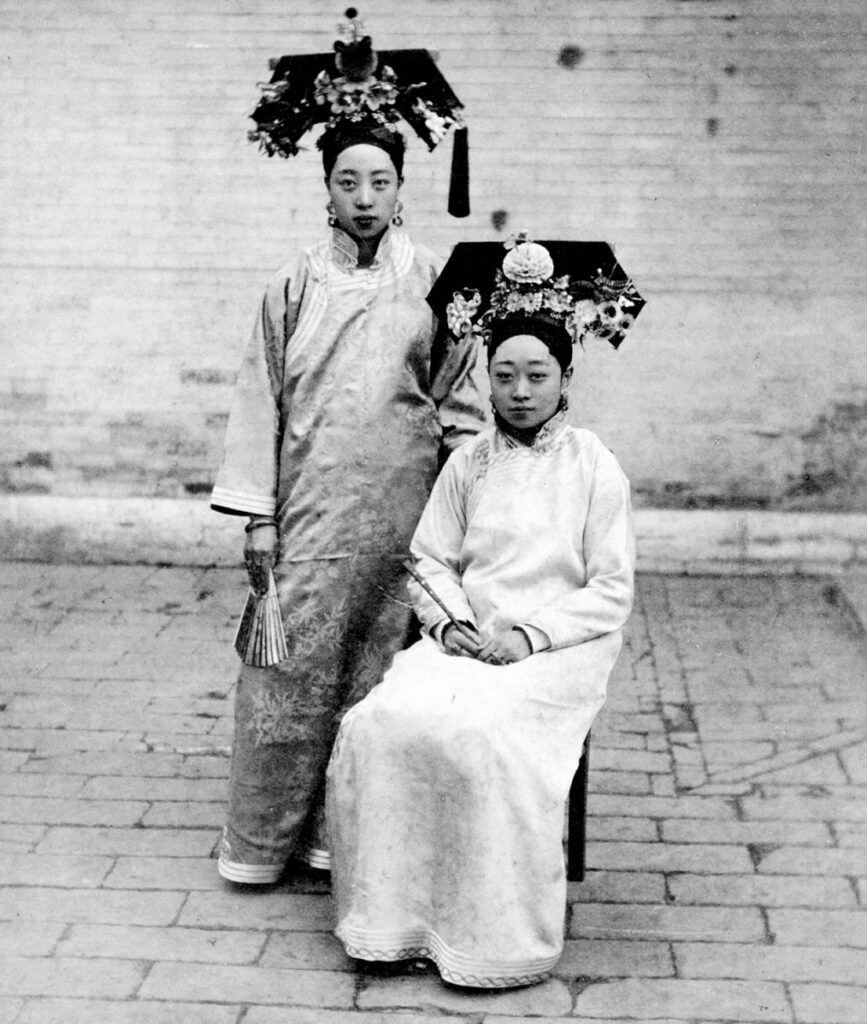

The script helped also in furthering the Chinese tradition of “sworn sisters”, women who were not biologically related but who committed to friendship. This tradition was developed between women of this period as social rules did not permit them to openly talk about personal regrets or the hardships of the agricultural life. Even while married and actively practicing the tradition of exogamy (brides used to join the husband’s family, moved in with them and not allowed to see their birth family, under the control of their husbands and mothers-in-law), sworn sisters would find solace in each other’s company. As a result, using Nüshu helped to create and maintain this bond in a strict patriarchal society.

Today, the resurface of the script has resulted in the opening of the “Nüshu Garden”, a museum that features classrooms and exhibition halls. Videos, paintings, tours of the museum and even classes are held there. The museum organizes summer camps to teach Nüshu to people that would like to feel a cultural reconnection to their land. Courses like this are also being taught at Tsinghui University in Beijing, proving that the usage of Nüshu and its role in society, has evolved.

In conclusion, in 2020 many years after the democratization of feminine power, Nüshu has completed its historical goal. It allowed women of the lower working class, who were marginalized and did not have access to education, to write and express themselves. Today, its mission is different. Today, it belongs to China’s cultural inheritance, embodied in beautiful calligraphy for future generations to uphold.