By Ana López Uso,

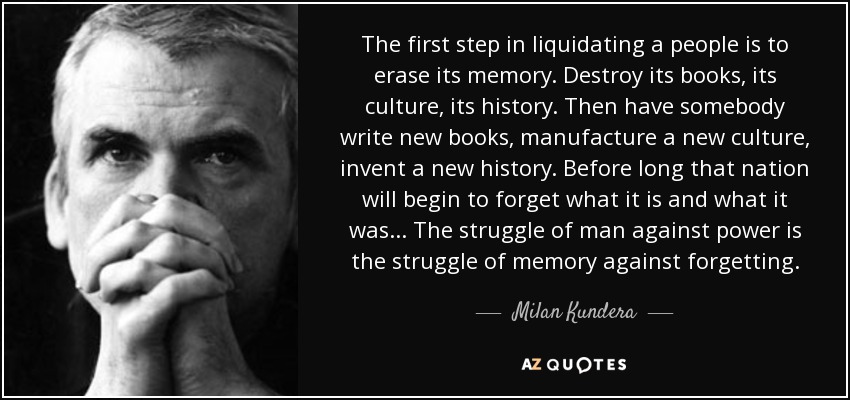

Milan Kundera, the renowned Czech writer, has been proclaimed winner of the recognised Franz Kafka 2020 literary prize in the Czech Republic. The recognition has come after a complex relationship between the exiled in France author and his home country, characterised by hostility and latter attempts of reconciliation. Since the withdrawal of his citizenship by the communist Czech government in 1979 and even after the arrival of democracy to the country, Kundera’s relationship with the Czech Republic has been anything but easy. However, the signs of reconciliation from the country to the author have been recurrent in recent times, trying to settle an enduring dispute that has kept the author away from his homeland for 23 years.

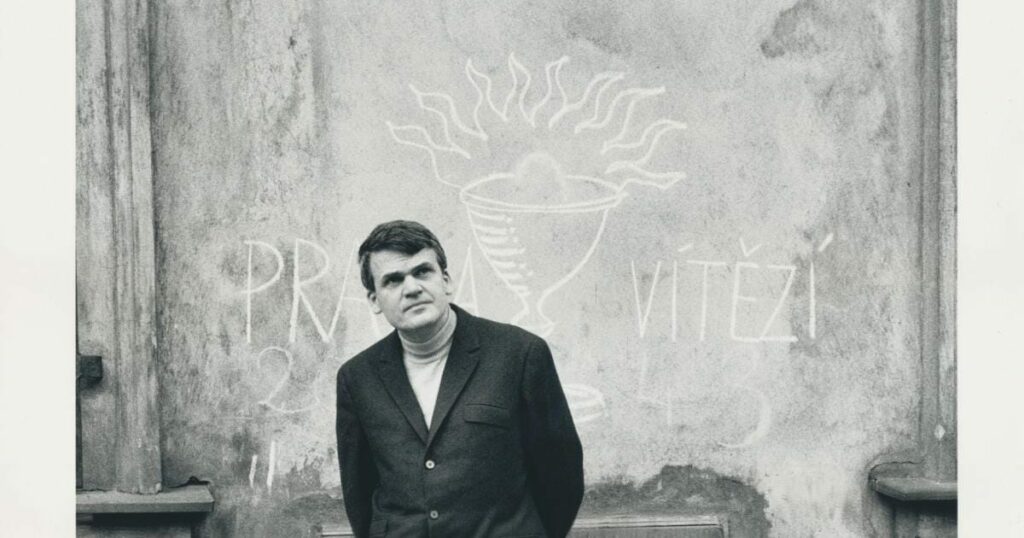

Milan Kundera was born in 1929 in Brno in Czechoslovakia, (current Czech Republic). He studied literature and aesthetics at the Faculty of Art, but leaving it unfinished, he went on to study film direction and script writing to the Film Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. During his early career, he intermittently belonged to the Communist Party: joining in 1948, he was expelled in 1950 for “anti-party activities”, being readmitted in 1956, and again expelled in 1970. Kundera’s resistance to the restrictions on culture imposed by the communist regime in Czechoslovakia led to his involvement in the reformist movement known as “Prague Spring” (1968), which many Czech artists and intellectuals supported denouncing the governmental repression of the arts. This involvement and the refusal to accept or cooperate with the new regime, led to Kundera’s blacklisting by communist authorities and the ban of his works in Czechoslovakia. However, Kundera continued speaking out against the harm of the oppressive state, what led to the firing from his teaching post in 1969, and the expulsion from the communist party right after. In 1975, Kundera, along with his wife, Věra Hrabánková, fled to France, where he took up a position to teach in the university of Rennes. In 1979, the Czech government stripped him of his citizenship, and two years after that, he obtained the French one. His second novel Life Is Elsewhere, was refused publication in his native country and was published in France and the United States. From that moment on, all his works, including his master-piece The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), were published in France and abroad, but banned in his homeland. In 1994, Kundera published his first novel written in French, La Lenteur (Slowness) and has adopted this language for his writing ever since.

Many have been the displays of disdain between Kundera and his native country. In 1979, four years after he had been in exile in France, the Czech government stripped him of his citizenship. In many occasions the author has proclaimed his works to belong to the “French literature” section in libraries, proclaiming himself a French writer. Another sign of the ongoing hostility is the author’s refusal to allow anyone but himself to translate his works into Czech – something he has not always chosen to do. As a result, many of Kundera’s later novels are not available in his mother tongue. In an interview with the New York Times in 1984, Kundera made the following statement:“Do I consider my life in France as a replacement, a substitute life, and not a real life? Do I say to myself:‘Your real life is in Czechoslovakia, among your old countrymen’? … Or do I accept my life in France – here where I really am – as my real life and try to live it fully? I chose France.” Kundera has thoroughly shared his vague idea of the meaning of homeland and the experience of “losing home”: “All I know is that before I left I was terrified of “losing home” and that after I left I realized – it was with a certain astonishment – that I did not feel loss, I did not feel deprived”.

Despite his rejection of ties with his home country, Kundera’s works are very much influenced by his country, and more specifically by the city of Prague. As the columnist Louise Ostermann writes: “Under his pen, the Czech capital becomes a mythical and treacherous entity. Prague seems to be a full-grown character of his novels, or at least an unavoidable inspiration. Kundera shares with the Central European authors he admires, like Kafka, an obsession with the polymorphic and muddled capital.”. To his feelings towards the city, Kundera has said: “There is no such dream of a return. I took my Prague; the smell, the taste, the language, the landscape, the culture.”.

In recent times, and after the democratization of the country, attempts of a reconciliation have been taking place by both sides. Kundera was awarded the Czech national literature prize in 2008, even though he did not attend the ceremony. A year later, he was awarded the title of Brno’s honorary citizen, to which he did not appear either. In 2019, the Ambassador of the Czech Republic in France, returned the Czech citizenship back to Kundera, following a three-hour meeting in a Paris restaurant with the Czech Republic’s Prime Minister, Andrej Babiš. Regarding his works, Kundera had not authorised the translations into Czech of many of his later works, but finally this year, the author permitted his most recent novel, “The Festival of Insignificance” to be translated into his native language. Earlier this summer too, it was known that Kundera and his wife would be donating their archive to the public library of Brno. And as a last gesture of agreement, the writer has deservedly received the most prestigious literary award on the Czech Republic. Vladimír Železný, Chairman of the Czech-based Franz Kafka Society, said Kundera had been awarded the Franz Kafka Prize because of his “extraordinary contribution to Czech culture” and his “unmissable response in European and world culture”. The author has been reportedly said to have accepted the prize “joyfully” being “honoured to receive the prize of a fellow writer.”

The signs of understanding come after many years of what seemed as an unsolvable disengagement. The bestowal of the Kafka Prize comes as the most recent attempt of leaving the dispute aside. Granting him this prize, signifies the restoration of his legacy as one of the most important ambassadors of Czech culture in his homeland, the Czech Republic. In the end, what the Czech Republic has given to Milan Kundera and what the author has given to Czech literature is a unifying force that years of dispute and distance will not be able to break apart.

References

- BRNO DAILY, Brno Publisher To Release First Milan Kundera Novel in Czech in 27 Years. Available here.

- CATHOLIC HERALD. Milan Kundera and the long argument with ‘home’. Available here.

- CZECH RADIO. Prague exhibition highlights Kundera’s relationship to translations. Available here.

- KAFKADESK. Milan Kundera: an ongoing struggle with Prague, forgetfulness and Central Europe’s uniqueness. Available here.

- NPR. Milan Kundera’s Czech Citizenship Is Restored After 40 Years. Available here.

- THE GUARDIAN. Milan Kundera ‘joyfully’ accepts Czech Republic’s Franz Kafka prize. Available here.