By Elena Chatzikosta,

Hearing the news that a mother has mutilated her 3-year-old daughter’s genitals, one might imagine that the incident had occurred in the medieval ages. Yet, this is also the reality nowadays. As a matter of fact, the specific case took place in 2019 in the United Kingdom and what is even more shocking, is that more than 5.000 cases of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) were recorded in the United Kingdom in 2017. Although FGM is a global concern, more than 200 million girls and women have been cut in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, where the phenomenon of FGM is most common.

Female genital mutilation involves the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. It is at the core of gender-based violence and is classified into four types. The first type is the partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the clitoral hood (the skin surrounding the clitoris). The second type is the partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the lips around the vaginal opening. The third type, the most severe of FGM, is the removal of the inner lips and/or the clitoris, while sewing together the outer lips (known as infibulation) and the fourth type includes all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, such as pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterizing the genital area.

Most of the girls are cut before turning 15 years old. In UNICEF’s survey in 2013 it was discovered that almost 80% of FGM cases in Somalia involved girls around 5 to 9 years old and in Nigeria more than 95% of the victims were from newborns to 4-year-olds. However, it is also a common practice amongst 18 to 49 year-old women, mainly in Egypt, Sudan, Mali, Sierra Leone and Guinea.

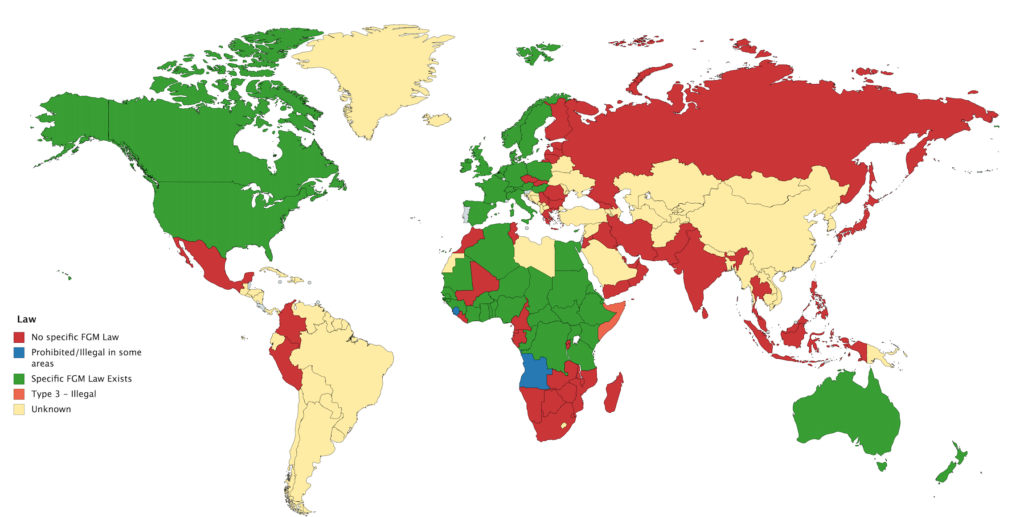

Based on a survey in 2013, Female Genital Mutilation is concentrated mainly in Africa, in countries, such as Tanzania, Sudan, Ethiopia and many more, while it is also found in Indonesia, Yemen and Iraq. It also takes place amongst immigrant populations in Western Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand. It is officially banned in most countries, but there are still 28 countries where mutilating a woman’s genitalia is legal or not mentioned at all. Although 28 out of 195 – the latter being the number of countries that exist in the world – seems as a small percentage, FGM is such a barbaric act that should not even be considered legal in any country.

Being widely practiced, FGM is supported by both genders, usually without question, and anyone that does not follow the norm may face condemnation, harassment and ostracism, so it is extremely hard for a family to decide against mutilating a girl’s genitalia when they lack the support of their community. The reasons behind FGM vary, but can be divided in five categories: psychosexual reasons, sociological and cultural reasons, hygiene and aesthetic reasons, religious reasons, socio-economic factors.

The psychosexual reason refers to the way to control women and their sexuality as it ensures virginity and fertility while it enhances the man’s satisfaction. Also, women are considered impossible to satisfy otherwise. So, by cutting off a woman’s clitoris you are taming her and getting her ready for a proper marriage, where her husband’s needs will be more important than her own.

The sociological and cultural reasons can be explained by the fact that FGM is practiced as part of a community’s cultural heritage and is seen as a girl’s initiation to womanhood while preparing her for marriage. In some communities, there are myths that contribute into the mindset that FGM is a harmful, but useful practice. Such myths include that the clitoris needs to be cut off or it will grow into a penis; or, that a child might die if, while exiting the womb, it touches the clitoris.

Also, FGM is practiced in order to promote good hygiene and encourage an aesthetic appeal since a woman’s genitalia in some communities is considered dirty or unclean, which means that by being mutilated it is purified and clean. Religion, like Islam or Christianity, might not officially support FGM, but some believers might use the religion’s doctrines in order to justify it.

Plus, having your genitalia cut off is an important factor in order to get married, so in many societies where women depend on a man for economic support, the family will practice FGM on their daughter, in order to secure that she will get married. If a woman is not allowed to work and provide for herself, she becomes completely dependent to a man’s desires and she is forced into doing whatever needed in order to be able to have something as simple as food on her plate.

FGM is extremely painful and doesn’t bring any health benefits; in contrast, it can lead to the permanent damage of the internal organs either by infections or through the actual procedure. It often leads to a woman bleeding to death (during the procedure or by giving birth later on) or being emotionally traumatised and scared. It is important that awareness is being raised, so people can unite into pressuring all countries to completely criminalise FGM. But even when and if a legal base is secured on the matter, there is still work to be done.

For example, sexual education needs to be properly provided to everyone all over the world where both genders will learn that sex should be a pleasurable act for both parties included, while also mentioning what FGM is and how harmful it is. It is also extremely important to provide economic and psychological support to the victims who have been through FGM while at the same time fight against the practice of it in these communities.

FGM is based on a sexist way of thinking that regards women as dirty and inferior to men while enhancing the mindset that women solely exist to get married, give birth and give pleasure to men. In conclusion, proper education, financial aid and support to the victims and the families that are deciding against FGM, is the most effective solution. Proper education is needed so women will understand that this practice is not a necessity and that it is extremely harmful; financial aid, so that they are in a place to decide against FGM without fearing that if they do not get married they will not survive; and finally support is important so that women can feel secure enough to decide against a kind of mutilation that is so inhumane.

References

- Female Genital Mutilation, WHO

- FGM: More than 5,000 newly-recorded cases in England, BBC

- Mother jailed for 11 years in first British FGM conviction, The Guardian

- Female Genital Mutilation, Unicef (Unicef Data)

- Types of Female Genital Mutilation, WHO

- FGM And The Law Around The World, Equality Now

- Female genital mutilation (FGM), WHO

-

Female genital mutilation (FGM) frequently asked questions, UNFPA