By Carmen Chang,

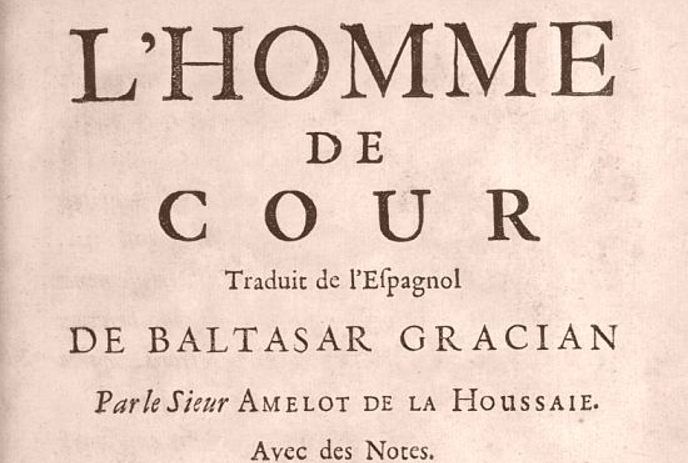

Paris, February 2021 – In a luminous seminar titled “L’Homme de cour dans tous ses états” held on 22 February 2021, CLEA of Sorbonne University hosted Professor Mercedes Blanco to explore the profound influence of Abraham-Nicolas Amelot de la Houssaye’s French translation of Baltasar Gracián’s Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia (1647). Widely known under the French title L’Homme de cour, Amelot’s 1684 translation emerged as a cultural and stylistic milestone in late 17th-century France.

A Translator as Mediator of Enlightened Discourse

Amelot de la Houssaye, a diplomat turned historian and translator, ventured beyond his official tenure as secretary of the French embassy in Venice (appointed 1669), facing imprisonment for his candid political commentary in Histoire du gouvernement de Venise—an episode that paradoxically fueled the book’s popularity, prompting twenty-two editions in three years and multiple translations.

Amelot subsequently turned to translating canonical texts—Machiavelli’s Prince (1683–1686), Sarpi’s History of the Council of Trent (1683), and Gracián’s L’Homme de cour (1684)—embedding his subversive insights within celebrated authors’ works. This approach allowed him to critique absolutist power subtly, appealing to the discerning bourgeois and the intellectual circles of the time.

A Text That Resonated Through Europe

Gracián’s Oráculo manual is a collection of concise, potent maxims offering guidance for social and political navigation. Amelot’s translation retained the compact force of its style, rendering French texts that emphasized discretion, elegance, and a strategic ethos of self-presentation. The dedication to Louis XIV and the rich paratextual apparatus manifested not merely translation but a statement of cultivated courtliness.

The first quarto edition (in-4°), lavishly adorned with a frontispiece depicting Louis XIV armored, holding a plan of Vauban’s fortifications, and a decorative bandeau and vignette designed by Pierre Lepautre, emphasizing prestige and artistry. A smaller, in-12° edition without the frontispiece appeared for wider circulation. The text’s resonance across Europe was immediate and broad: it inspired translations into English, German, Italian, Russian, Polish, and Hungarian —sometimes unacknowledged or subtly shaped by Amelot’s influence despite translator criticism or polemic over his liberties.

Translation Philosophy and Strategic Tactics

Professor Blanco illuminated how Amelot’s translator’s craft involved both fidelity and finesse. In his preface on the “Defense of Laconicism,” Amelot argued that brevity and obscurity heighten desire, reserving meaning for the cultured few while intriguing all. In grappling with a metaphor by Joseph de Courbeveille, Amelot admitted —“I softened metaphors too strong, relocated some thoughts, changed meaning proper to figurative or figurative to proper”— revealing his editorial subtlety and strategic refinement.

He positioned himself as both disciple and mouthpiece of Gracián, defending against those who deemed the text “intraduisible.” The challenge was set by Father Dominique Bouhours in his Entretiens d’Ariste et d’Eugène (1671), which sparked Amelot to stake a claim for justice —not for himself, but on behalf of the text and its values.

An Enduring Legacy in Translation and Cultural Studies

The seminar’s speaker emphasized that Gracián remained relatively absent in 17th-century France —even with efforts by Joseph de Courbeville and Étienne de Silhouette— until Amelot’s translation bridged a cultural gap. The seminar’s interdisciplinary perspective —combining literature, civilization, and translation studies— offered a profound and enlightening framing, especially for newcomers to the subject, as conveyed by a participant in the program.

Despite not aligning directly with their research theme, the attendee found Amelot’s historiographical strategies particularly resonant. The notion of the translator as servant to author remains vital in contemporary translation debates.

In sum, Professor Blanco’s seminar exceeded expectations: richly detailed, methodologically innovative, and deeply contextual. It unfolded a multifaceted exploration of how a translator’s artistry can shape reception across eras, languages, and cultural milieus.

References

- Mercedes Blanco. “L’Homme de cour dans tous ses états”. seminar, CLEA. Sorbonne Université. 22 February 2021.

- Baltasar Gracián, Oráculo manual y arte de prudencia (1647); French translation L’Homme de cour by Abraham-Nicolas Amelot de la Houssaye, Paris, La Veuve-Martin & Jean Boudot, 1684 (in-4°, with frontispice and decorative elements by Pierre Lepautre); in-12° edition without frontispice.

- Suzanne Guellouz, Du bon usage des textes liminaires. Le cas d’Amelot de la Houssaye, Littératures classiques 1990.

- Dominique Bouhours, Entretiens d’Ariste et d’Eugène (1671), referenced in the seminar context.