By Carmen Chang,

In a thought-provoking academic session organized by CLEA (Centre de recherche sur les langues et l’écrit dans l’Antiquité et au Moyen Âge) at Sorbonne Université, two young researchers explored how rhetorical and literary values shaped early modern Spanish eloquence. The conference, titled “The Invention of Eloquence: Linguistic Consciousness and Literary Values in the 16th and 17th Centuries,” featured presentations by Marie-Énglantine Lescasse, a doctoral candidate at the University of Caen, and María Gutiérrez Campelo, a doctoral candidate at the University of León.

Together, their presentations shed light on two interrelated themes: the birth of Spanish eloquence through the lens of rhetorical tradition, and the controversial rise of lexical cultismo in the poetry of Luis de Góngora.

The Roots of Spanish Eloquence: Between Grammar and Rhetoric

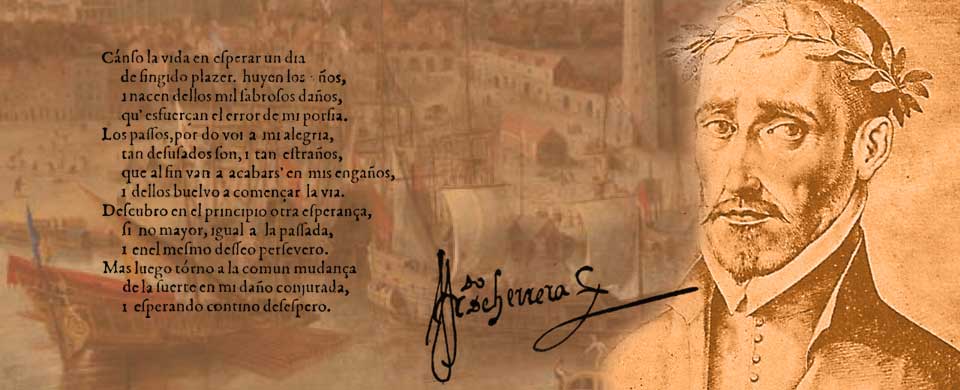

Marie-Énglantine Lescasse opened the session with a historical and conceptual exploration of Miguel de Salinas, a lesser-known but foundational figure in the development of rhetorical thought in Spain during the mid-16th century. Her presentation “The Birth of Spanish Eloquence: Miguel de Salinas and the New Importance of Elocution in 1540s Spain,” revealed how Salinas’ engagement with classical rhetoric gave rise to a Spanish vision of eloquence rooted in both grammatical purity and rhetorical elegance.

Salinas, a Jeronymite monk, was portrayed by José de Sigüenza as a deeply learned man who immersed himself in Latin rhetorical corpora. Lescasse emphasized his desire to refine language through precise word choice, drawing a clear line between grammatical correction (recte dicere) and rhetorical beauty (bene dicere). In doing so, Salinas positioned himself as a pioneer of a distinctly Spanish rhetorical tradition—one marked by purism, clarity, and intellectual rigor.

His work was influenced by Antonio de Nebrija, Spain’s leading humanist, whose 1515 Artis rhetoricae compendiosa coaptatio foregrounded the role of inventio while devoting an entire chapter to elocutio. Notably, Salinas emphasized that elocution depends on individual word choices and their composition—“la elocución se considera en cada una de las palabras en especial en la composición de unas con otras.”

Lescasse then traced how this view influenced later theorists like Andrés Sempere (1546) and Alfonso de Zorrila (1543), though with diminishing focus. Elocution, once central, was gradually reduced to stylistic ornamentation, as seen in the works of Alfonso García Matamoros (1548). The rhetorical vigor Salinas once promoted was being diluted, opening space for new linguistic tensions—particularly those posed by literary cultismo.

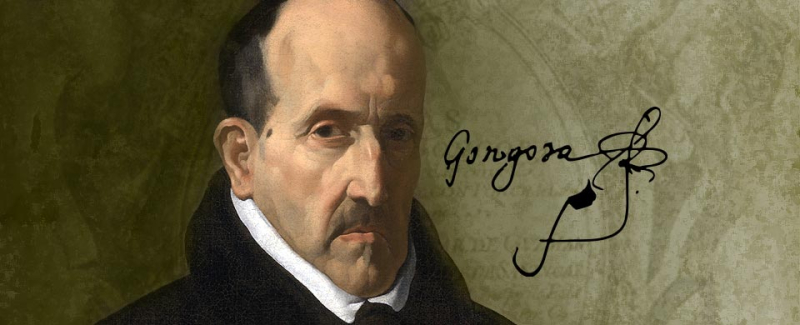

Góngora and the Lexical Cultismo Controversy

Turning from rhetorical theory to poetic practice, María Gutiérrez Campelo offered a detailed examination of Luis de Góngora, the Cordoban poet known for his culteranismo—a highly ornate and learned style that polarized his contemporaries. Her presentation, “Voces nuevas y peregrinas: Approaches to Lexico-Semantic Cultismo in the Age of Góngora,” interrogated the linguistic ideology behind the poet’s controversial use of cultivated, foreign, and Latinate vocabulary.

According to Gutiérrez Campelo, Góngora’s poetic style was frequently criticized for its opacity and intellectual difficulty, characteristics closely linked to his incorporation of lexical cultismos —words borrowed or modeled on Latin and Greek roots. The term itself, cultismo, refers to this influx of scholarly or exotic vocabulary, sometimes also labeled as “new,” “foreign,” or “pilgrim” words (voces nuevas y peregrinas).

The presentation also highlighted how these linguistic choices triggered intense debate. Critics such as Francisco de Quevedo lampooned Góngora’s use of Latinisms and Grecisms, claiming they distorted clarity. Quevedo, for example, mocked what he saw as an unnatural mixing of languages. Others, such as Correas (1625), recognized the growing presence of Latin structures in Spanish prose and verse, while Almansa y Mendoza (1613–1614) urged the moderation of Latin influence. Ponce, in a letter from 1617, lamented how foreign influence “defaced the sweetness and clarity” of Castilian Spanish.

Gutiérrez Campelo proceeded to categorize different types of cultismos using examples from Góngora’s corpus. These included:

- Lexical cultismos: causa, artículo, canoro

- Phonetic cultismos: digno (dino), obscuro, afecto

- Semantic cultismos: discurrir, transportar

- Morphological cultismos: regularización, integridad

- Syntactic cultismos: hipérbaton, acusativo griego

Beyond Latin and Greek, Góngora also incorporated Italianisms such as tramontar, revealing a multilingual mosaic that was as radical as it was literary. Gutiérrez Campelo concluded with a call to revisit the work of Dámaso Alonso, whose exhaustive analysis of Soledades remains a foundational reference, while also urging new taxonomies and conceptual frameworks to better understand cultismo today.

A Challenging but Thought-Provoking Encounter

While both presentations were rich in historical and linguistic insight, the didactic clarity of the session left something to be desired for a broader audience. The first talk, in particular, was dense with citations and lacked concrete examples, which made it difficult to follow the distinctions between rhetorical categories like dispositio and elocutio. The second presentation was comparatively more accessible—especially for those familiar with Góngora’s biography and work—but still glossed over certain complexities in the classification of cultismos.

For students and researchers without a solid background in classical rhetoric or early modern Spanish literature, the content may have felt demanding and overly theoretical. Nonetheless, the conference succeeded in exposing attendees to an essential chapter in Spain’s cultural history, one where language, identity, and art converged with remarkable intensity.

Reflections and Takeaways

Ultimately, this session served as a reminder that eloquence is not merely stylistic flourish, but a marker of cultural values, intellectual heritage, and even national identity. In the tension between purity and innovation, between Latin legacy and vernacular evolution, lies a story not only of how Spanish came to be written, but of how it came to express thought, art, and power.

For aspiring researchers, the conference offered more than just a timeline of ideas—it raised important methodological questions about how to communicate scholarship. As one attendee reflected, “If I were to present a conference someday, I would keep in mind that much of the audience may be unfamiliar with the subject matter. Clarity, structure, and accessibility are crucial.”

Though the event may not have offered direct insights for everyone’s research focus, it provided fertile ground for intellectual curiosity and future exploration—especially in the ever-evolving dialogue between linguistic form and literary function.

References

- Lescasse, Marie-Énglantine. “La naissance d’une éloquence espagnole : Miguel de Salinas et la nouvelle importance de l’élocution dans l’Espagne des années 1540.” Paper presented at the CLEA Conference, L’invention de l’éloquence, Sorbonne Université, February 11, 2021.

- Gutiérrez Campelo, María. “Voces nuevas y peregrinas. Aproximación a la cuestión del cultismo léxico-semántico en la época de Góngora.” Paper presented at the CLEA Conference, L’invention de l’éloquence, Sorbonne Université, February 11, 2021.

- Nebrija, Antonio de. Artis rhetoricae compendiosa coaptatio, 1515.

- Correas, Gonzalo. Arte de la lengua española castellana, 1625.

- Almansa y Mendoza, Andrés. Advertencias para la lengua castellana, 1613–1614.

- Ponce, Luis. Epístola al Conde de Villamediana, 1617.

- Quevedo, Francisco de. Obras, 1661.

- Alonso, Dámaso. Estudios y ensayos gongorinos, mid-20th century.