By Chrysa Skrimpa,

The term “problematic” has dominated online discourses for the past few years and has ruthlessly swept along numerous pieces of media and creative works, as well as artists, content creators and public figures. An individual has a problematic opinion or behavior; a work of art revolves around problematic themes; a piece of media employs problematic rhetoric; it is not clear where the spectrum of the term lays its borders, only that it always refers to cases of non-conventional morality and anything it influences directly or indirectly. Of course, when it comes to individuals, and especially those that influence public speech, it is useful to be informed about their opinions and positions, and take a stance depending on one’s beliefs. However, due to the expansion of the term to refer to pieces of media and works of art, several questions are raised regarding the perception of morality in art and fiction, and the way it influences the works we choose to engage with.

The obsession with morality in fiction and the demand for works of art that promote purity of character is not recent; indeed, it dates back to England’s Georgian era and the moral panic caused by M. G. Lewis’s The Monk. Today, this kind of obsession seems to have become more widespread through the internet; lists of ten unproblematic books so that the reader will not be afraid of a “call out” by a theoretical audience, posts that expose the bigoted opinions of authors long dead, self-proclaimed character apologists, all make the internet rounds in order to make sure our interaction with art is morally enriching, sanitized, and free of themes that may trigger or disturb our sensitivities. There is a constant need to prove that we are good people, but goodness is suddenly a performance that is carried out by fiction, rather than a fact rooted in reality. As a result, we are to avoid anything morally challenging, anything that reproduces problematic themes; inevitably, we are doomed to an intellectually limited bookshelf, and non-existent reading comprehension.

There are two reasons we read fiction; the first one is to gain a new perspective, one that we possibly wouldn’t be exposed to otherwise. It is the purpose of fiction to absorb us in the vastness of the human experience, and this consequently means that a character presented in a sympathetic light, a character that triggers our empathy, is not necessarily a good person. “Desires and feelings,” Walton asserts, “do not constitute moral commitments.” When the readers find themselves liking the “bad guys” it does not automatically mean their ethics are suddenly twisted and irreparably damaged; it simply means that, when it comes to feeling, humans are all the same.

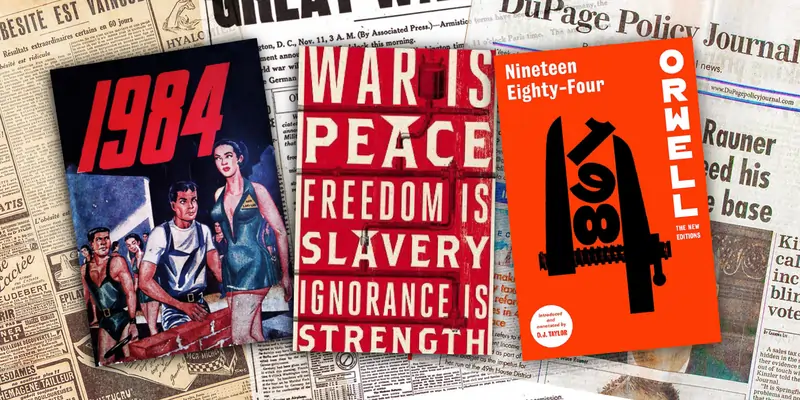

Of course, the above claims only refer to one case. A reader does not have to identify with a character; they don’t even have to like a character. We read fiction not only to stare into a mirror, but also to expand our knowledge of the human mind, or the way society works. No one will accept Humbert’s judgement in Lolita; the book exists to present and condemn, rather than force, a certain perspective. By having Winston objectify Julia in 1984, Orwell does not promote sexual assault; he offers an interpretation of the damage and repression that a society like that can induce upon the individual. The reader is free to imagine such states as much as they are free to reject them. Their thoughts are not policed; a fictional consideration is not akin to a virus that will contaminate their brain. It is important to engage in character study, to understand motives and worldviews, to examine the factors that have contributed to their shaping. It is okay to be disturbed; the purpose of art is sometimes to be disturbing, to challenge our truths, to make us uncomfortable and force us to revisit and reestablish our values. Character study certainly does not equal endorsement; otherwise countless societies of literary scholars would be crumbling to the ground. As long as the reader employs their critical thinking skills and recognizes right from wrong, their morals are not in danger.

The second reason that we read fiction is, naturally, to enjoy ourselves and entertain our imagination. Reading for enjoyment does not require a lecture in morals. The reader is well-aware of the characters’ qualities, and is entertained by the ones they find interesting, rather than the ones with flawless morals and perfect handling of situations. After all, characters are not real people; they are narrative devices, constructed as such in order to forward the plot, and make for an exciting read. There is no narrative without conflict, and conflict requires well-written, fleshed-out characters, thought-provoking themes, and a genuine exploration of the human nature. No action has to be justified, and no character is in need of apologists. It is still fiction.

Walton ponders on why the readers accept without doubt that, for the purpose of a story, aliens exist, or a sentence they don’t find funny causes amusement, and not that a story deals with fictitious immorality, although in both cases everything depends on the readers’ imagination. Perhaps, due to it not existing in a vacuum, immorality scares us. We are so focused on securing our goodness that in the process of doing so we dehumanize immoral deeds, because of the fear that we, as humans, are also capable of them. Alternatively, one may attribute this obsession with morality to conservatism and the rise of purity culture, which frees the way for any work that refuses to conform to be deemed as immoral; or the modern perception of art as a product to be consumed, which brings to the surface the idea that you are what you own. No matter the cause, the need for critically engaging with a variety of works remains. The more we shy away from anything “problematic,” the less we develop critical skills, and the less we are able to recognize real-life problematic situations, and navigate society itself.

References

- Morals in Fiction and Fictional Morality. JSTOR. Available here

- For Goodness’ Sake. Bookforum. Available here