By Chrysa Skrimpa,

Any woman who has spent a considerable amount of her teen and young adult years online will one day possibly find herself silently pondering; am I just a girl, or am I a divine entity whose roots reach deep into the earth’s core and entwine with the spirit of every woman that has ever graced the earth’s soil with her footprints? The answer is, unfortunately, none of the two.

These two trends have been dominant in social media in the past decade, with the “I’m just a girl” one in particular emerging a couple of years after the COVID-19 pandemic. This concept of girlhood especially seems to create specific perceptions around women and what it means to be a woman, a question that points towards not only feminist and queer discourses but also, your daily TikTok rant. So, what does it mean to be a woman? What does it mean to be a girl?

A girl, as perceived by the above trend, resembles more of some sort of creature rather than a fully fleshed out, real person. A woman who is just a girl cannot be burdened with major responsibilities; she cannot be expected not to make a mistake, she is just a girl after all. She is totally estranged to the concept of math, and employs a kind of “girls only” math to pay for a “girl dinner” that includes items progressively more distant from actual food. She has embraced her secondary position; she has undermined her skills and potential; she is no longer a person capable of growth and logical thought; she is just a girl.

The divine feminine, as it is called, at first seems to occupy the other side of the same spectrum, which consists of an attempt to find meaning in womanhood. Women are glorified; they are not merely people, but have a deep instinct, a spirituality that is considered inherent in every woman, a connection with nature and a unique emotional range. A woman’s instinct never lies; women have a kind of knowledge, of wisdom, unattainable by men. They are goddesses incarnate.

Both trends construct an image for women to relate to. Both trends are ceaselessly reproduced by aesthetic TikToks and Instagram posts, mood-boards and playlists that present a desirable identity, a safe mold for women to fit in and construct their subjectivity on. As such, these trends have two things in common; their initially innocent purpose, and their harmful reproduction of stereotypes.

The need to define the “female experience” is not new; experience has often been regarded as an authority in feminist discourse, a seemingly reliable tool to promote women’s skill and equality. These trends attempt to do something similar; either by elevating women, or by creating a safe space for them to be flawed and silly, they universalize and unify the female experience in order to promote a sense of understanding, of solidarity, of inherent worth that women have been culturally deprived of.

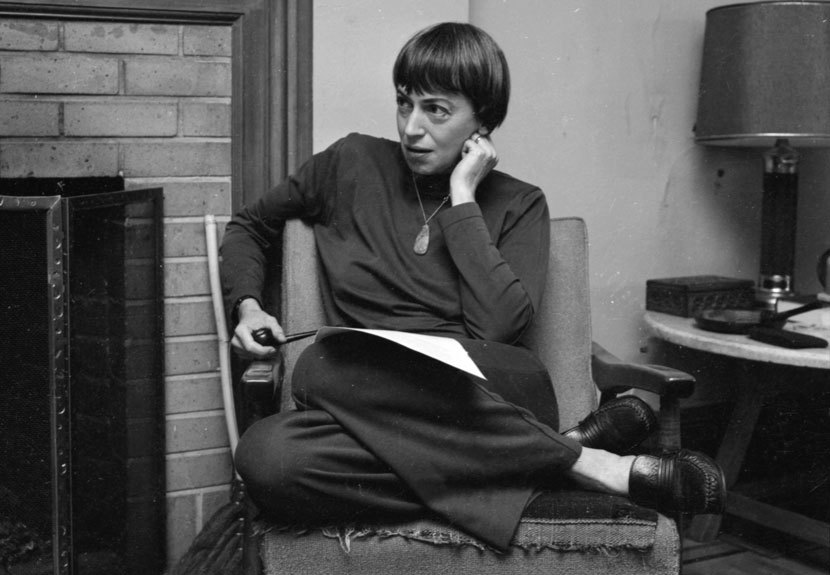

Inevitably, however, both end up reproducing harmful stereotypes that further confine, rather than liberate women. Womanhood is once more balancing on the two most destructive pillars of misogyny; objectification, and a woman’s single purpose of nurturing. It does not matter whether you are just a girl, or you are a divine entity. Either way, you do not belong in the public sphere. You are not competent enough, or alternatively, your true purpose is natural, pre-destined, essentially a vessel of reproduction. Women’s minds and skills end up utterly diminished, and they once again become dependent on men. Ursula K. Le Guin similarly claims that the divine feminine especially “reinforces the masculinist idea of women as primitive, inferior; women’s knowledge as elementary, primitive […] while men get to cultivate and own the flowers and crops that come up into light.” Thus, what has started out as a cute trend ends up reproducing a harmful rhetoric that serves the patriarchal system.

“Why should women keep talking baby talk while men get to grow up?” Le Guin then asks. “Why should women feel blindly while men get to think?” To these questions, this article may add; how does the gender binary perpetuate these ideologies?

The above trends, if observed closely, seem to apply traits to women that are essential, thus constructing what they believe to be an inherent experience of femininity. However, no matter how positive and empowering these traits are presented as, they are still rooted in the notion that there are fixed qualities that distinguish men from women. In effect, as Nicola Gavey accurately supports, due to their being essentialist, these qualities merely reproduce the status quo. They do not include the vast variety of experiences as they are told by women of different ethnicities and cultural backgrounds, transgender women, disabled women, poor women, thus ignoring and further marginalizing a crucial part of society. So, they eventually become fossilized, and end up catering to what is the perceived or desired experience of white, heterosexual, upper middle class women.

The key in order to deconstruct any kind of similar trend is to realize that there is no universal experience. The way one may experience womanhood is no trend or stereotype, but rather depends on the social, cultural and political context, and the gender roles they construct. Therefore, the meaning of being a woman has to be analyzed according to power relations and how they affect race, gender, class and even fundamental human rights. Eventually, solidarity does not stem from a single common experience that will trend on TikTok for a month; it depends on the ability to accept and consider all experiences of womanhood, and let that variety serve not as a weakness and a cause for infighting, but as feminism’s greatest strength.

References

- Feminist Post-Structuralism and Discourse Analysis. Wiley. Available here

- What Women Know. Ursula K. Le Guin. Available here