By Athina Varvesioti,

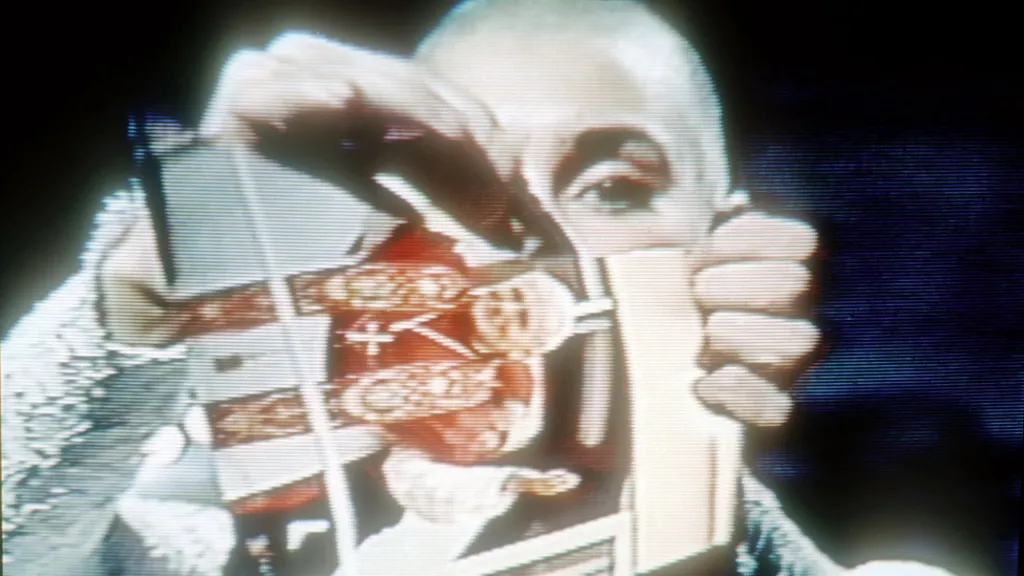

In 1992, Irish singer and songwriter Sinéad O’Connor tore a picture of Pope John Paul II on Saturday Night Live, in a bold, daring gesture of protest against religious oppression, and in particular, against the sexual abuse of people within the Catholic Church, by the Church itself. At the time, her act was condemned, her records were burned and she was marginalized as someone who did nothing but desecrate a symbol of faith for millions globally. In hindsight, however, Sinéad’s bravery and determination to expose the hypocrisy and cruelty of a Church that preaches love and benevolence is perceived as a landmark in the relationship of the music industry with religion and the traumatic experiences of artists, or people in general, with it.

Many artists, coming from a plethora of genres, have attempted to portray notions of religious trauma and oppression in their music, either in a poetic and delicate, or in an aggressive and raw way. In order for us to examine how this can occur, it is significant that we comprehend what religious trauma is. When we discuss religious trauma, we discuss the amount of negative experiences an individual has accumulated throughout their lives with regards to religious practices they have been forced to accept and follow. It can range from emotional and sexual repression to physical abuse. Those who suffer from religious trauma often exhibit intense, unjustified feelings of guilt, fear and shame that have been evoked due to teachings that place the utmost importance on “purity culture”, or crucify anyone who expresses carnal desires or any opinion that is pitted against them. Such humans may often be discriminated against, ostracized, and thus faced with a constant sense of alienation, even after they have been excommunicated and detached from the said religion.

Since music is a form of art via which artists externalize their concerns, it stands to reason that those who either have such experiences with religion, or who are enraged and disenchanted with its practices on the whole, will take a stance through their artistic production. Artists from Ethel Cain and Tori Amos to Ghost and Nine Inch Nails have stepped forward in order to share their own personal experiences, in an endeavour to bring together those who have undergone the detrimental effects of religious oppression and to offer a form of consolation and a sense of solidarity.

When Ethel Cain sang God loves you, but not enough to save you, she encapsulated the struggle of people who have been wavering in their own faith due to traumatic experiences stemming from its practice. The American singer and songwriter, in her album Preacher’s Daughter, narrates her own perplexed relationship with her faith, and her doubts with regards to the presence of God in her life. She poses a question towards the omnipotent, omnipresent God she has been taught to worship: if you embrace and love each and every one of us, why can you not release me from my ordeals and end my torments? Her disillusionment with religion comes as an offspring of her upbringing within a strict religious environment; she fearlessly —and rather poetically— addresses God and those who introduced her to Him, seeking for answers.

Speaking for all the individuals who have had to perceive God as a punisher rather than a forgiver, Ethel maps her journey towards a complete descend into darkness, for she has not learnt what it means to abandon her faith; it is all she has ever known. Eventually, in a state of emotional turmoil, she is involved with and devoured, literally and metaphorically, by an abusive partner. In a similar manner, individuals who decide to leave the religious environment they have grown up into, encounter severe difficulties in their daily life, for they seem incapable of disposing of the feelings of guilt. It is likely that, just like the woman in Ethel’s story, they are trapped in harmful situations from which they might never escape. They can only visualize their life through the lens of faith.

American pianist and singer Tori Amos, daughter of a Methodist minister, has repeatedly offered her own interpretations of faith. Incorporating feminist perspectives in her understanding, she criticizes the patriarchal aspects of religion and how the ardent love that Christianity, in particular, stands for, can turn into something abusive. This criticism of the lack of the feminine divine becomes evident in her song God, whereby she confronts God Himself, desperately trying to figure out why He does not “come through”. She asks Him if he needs a woman to look after Him, dismantling the concept of the domination of male figures in the world at the expense of women, who are often subjugated and silenced. Tori’s melody of emancipation is directed towards everyone who has ever felt repressed in a religious environment, and offers words of reassurance and solace to those who have witnessed their faith crumble down in front of them.

She sings for people whose agonies and fears have been diminished by the religious teachings of their community, whose desires and thoughts have been buried deep inside them. The song is a celebration of love, of the female body that religion, once distorted, often exploits and undermines, in quite a paradoxical way. Tori is faced with the God who was supposed to protect and embrace her, like a wounded, frustrated woman, asking Him why He is using his power to control and silence her, among others. Of course, she is referring to the Church, who is supposed to preach the word of God, but usually presents this word in a way that births fear and guilt.

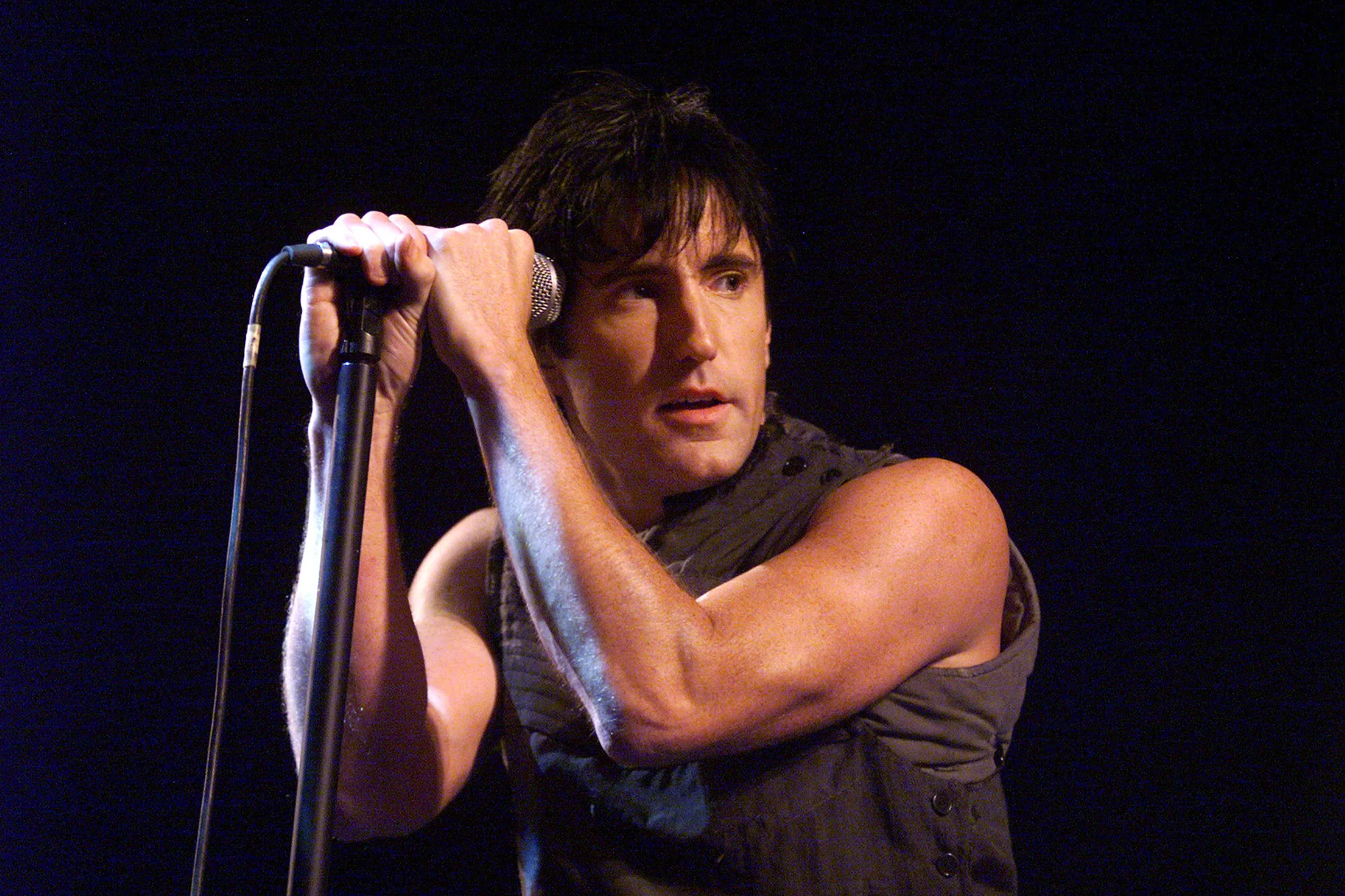

There are some artists who do not content themselves with subtle criticisms suffused with delicacy, but opt for straightforward mockery of religious hypocrisy. In 1994, industrial rock legends Nine Inch Nails released their critically acclaimed album The Downward Spiral, to mixed reviews. Their singer, Trent Reznor has not explicitly stated that he has been suffering religious trauma and yet, he uses his voice to fire against those who distort and utilize religion for their own, unholy intentions. In Heresy, a song that sparked debate at the time, Reznor discusses blind faith, and urges the world to critically examine what is served to them by religious figures in authority. He denounces religious hypocrisy and oppression, and goes as far as to claim that people in authority within the Church fabricate tales and misguide those who seek for love and acceptance from it. He emphasizes the manmade nature of many concepts and ideas that are allegedly existent in dogmas. Essentially, Reznor stands weak and helpless in the face of God, unable to be in charge of his life and desires. Nihilistic as it may sound, it echoes the reality of those whose faith has been a burden rather a haven.

In their efforts, such artists do not aim to condemn religion in its true form, for it is a shelter to many. Their criticism is aimed at those who abuse their power within the Church, and those who present religious dogmas in favour of their own reality and at the expense of others. As Sinéad herself said, “Fight the real enemy”.

References

- Sinead O’Connor’s ‘SNL’ Protest Was ‘Monumental’ for Church Sex Abuse Survivors. Rolling Stone. Available here

- Religious trauma: Signs, symptoms, causes, and treatment. therapist.com. Available here

- The life and death of Ethel Cain. The FADER. Available here

- Ethel Cain – Preacher’s Daughter Review. Still Listening. Available here

- Tori Amos and Religious Trauma Syndrome. The Polyphony. Available here

- Came Back Vaunted: An Interview with Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor. The Skinny. Available here