By Dimitris Kouvaras,

South Korea is known for many things: Samsung, its futuristic capital of Seoul, the Korean War and hostile relations with North Korea, anime, or even famous K-pop stars. As for the latter, what is often striking -although now normalised- to the western eye is their presumably effeminate appearance, including no facial hair, makeup use and vivid hair colour schemes. However, although Western perceptions of the country’s gender norms have usually focused on the Kkonminam, or flower boy trend, a new movement concerned with gender dynamics has made headlines over the last years, indicating latent forces of gender inequality and repression of women and becoming the cause of heightened social division. The so-called “4B” movement, portraying itself as a radical feminist cause, indicates how historical, economic, and social factors within Korea’s capitalist society have led many women to adopt a staunchly man-free lifestyle.

The name “4B” stems from the core of the movement’s ideology, which lay in the rejection of what are considered the four patriarchal institutions or social acts dominating traditional women’s gender roles and fostering the submission of female bodies to the desires of men. Bihon, i.e. the refusal of (heterosexual) marriage, is the first axis of the movement’s liberating strategy, which substitutes marriage with individual empowerment and financial independence. The second axis is Bichulsan, i.e. the refusal of childbirth, combating what is considered a primary source of infringement on female bodily liberties and dependence on patriarchal institutions. Whereas these first axes object to certain male-referring landmarks in women’s lives, the last two aim to regulate and extinguish all forms of non-friendly interactions with men through abstention from (heterosexual) romantic relationships (Biyeonae) and sexual relationships alike (Bisekseu). Even though “4B” ideology restrictions only refer to interactions with men, the movement has little homosexual undertones. For the women involved, it’s a matter of survival and women’s social rights more than sexual preference. Still, these four negations seem unfathomable based on how impactful and restrictive of social relations they are.

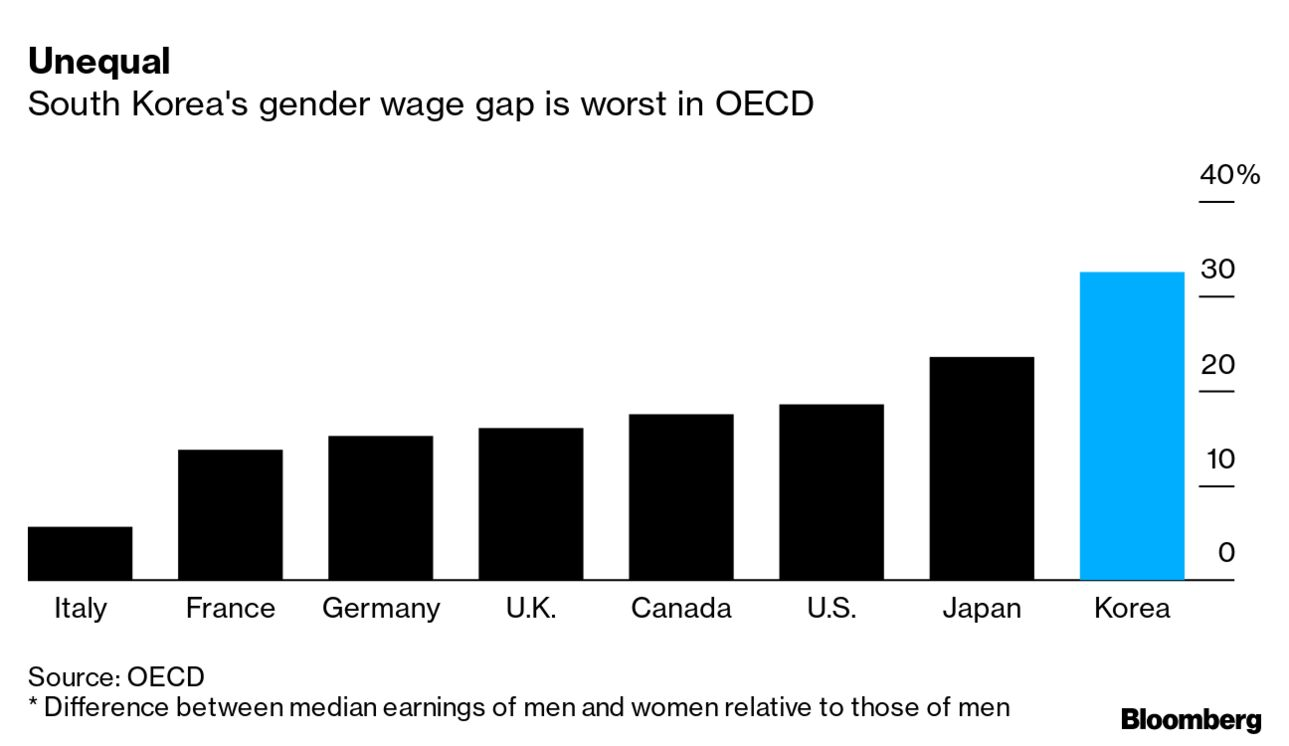

The movement spread in the mid-2010s, a decade which saw the belated and more general emancipation of Korean feminism amidst growing social tensions. The reasons behind women’s consternation were multiple and stemmed from aspects of Korea’s history, capitalist economy, demography, and Confucian patriarchal tradition. Cheap female labour was consistently exploited since the Japanese occupation of 1905 and the following industrialisation of the peninsula, a trend that continues today as the country sustains the largest gender pay gap of all OECD members, amounting to a whopping 31% in 2022. After the first feminist wave as part of the Minjung anti-dictatorial movement of the 1980s, the 20th century saw the diversification and consolidation, and emancipation of feminism in the country amid changing socioeconomic dynamics.

Having experienced an economic boom since 1956 that entailed rising living standards, rampant urbanisation, and demand for educated workers, Korea, since the beginning of the 20th century, faces the pathogenies inherent in most developed economies. Women’s increased university enrolment and extensive participation in the labour market coincided with dwindling birth rates across the country and a dual labour and housing market crisis relating to the ramifications of urbanisation. Young people found themselves grappling with time-consuming qualification demands and dismal work prospects, leading to the creation of the term 3-po generation for those born around or after 2000, i.e. the generation that was forced to quit marriage, romantic relations, and childbirth due to socioeconomic pressures and Korea’s perfectionist tradition that led to a workaholic culture.

In that context, a dismissive and antagonistic male attitude against women developed by the 2010s that scapegoated their education and career ambitions for the country’s demographic and economic ills, proving the perfect breeding ground for patriarchal gender stereotypes. The structural character of this ideological current was made apparent in 2016, when the government of former president Yun Sook Yeol published the National Birth Maps, documents that visualised the number of women of reproductive age per region and were rightly seen as instrumentalising the female body for reproductive purposes. Meanwhile, the advent of smartphones led to a rise in porn spy-cams that illegally captured women’s intimate moments, often in public spaces such as restrooms, which again vulgarly objectified and sexualised the female body for the pleasure of men irrespective of human dignity and privacy concerns. Spurred by the deadly stabbing of a 23-year-old woman in a public restroom, which was termed a “femicide”, these patriarchal pathogenies erupted in 2016 leading to the creation of the 4B movement, which sprung from online women communities and belonged to a wider context of feminist awakening that encapsulated more widespread movements such as #MeToo and Escape the Corset.

After Donald Trump’s election in 2024, 4B also spread in the US, although due to different causes, relating to the lifting of the constitutional abortion protections by Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which infringed on women’s bodily autonomy. However, the Korean movement’s roots are way deeper. An advocate of the movement emphasises that 4B is about “keeping women safe” at a place where “feminist” is often used as a demeaning slur. Abstention from relations with men thus arises from the perception of these relations, whether marital or casual sexual, as structurally manipulative against women, whose bodies are objectified and agency deprived. This signals the presence of a profound gender schism in Korean society, as well as the state’s unwillingness or incapability to escape the reproduction of patriarchal social institutions. If that persists, women will have good reasons to be concerned.

However, although 4B is undoubtedly capable of offering women safe spaces and enhanced margins of personal autonomy, some of its aspects could be considered as potentially problematic. From an economic standpoint, whereas the movement arose as a means of combating gender injustice and increased social strains of produced by a workaholic and antagonistic capitalist system, some of its adherents stress the reorientation of women’s agency towards personal and career development rather than relationships with men. In that respect, 4B could end up feeding the very capitalism whose local shortcomings are by and large responsible for women’s troubles in Korean society, potentially reproducing the pathogenies related to the 3-po generation.

When it comes to relations with men, on the other hand, the total negation of non-friendly relations could end up reifying the image of a heteronormative world where male and female are inherently opposites with no room for convergence. Although 4B does include some references to lesbianism, these remain on the periphery of its ideology, which could be perceived as dualistic. However, dualism entails an inherent rigidity that is incompatible with the examination of social categories and relations, which are multidimensional products of cultural and social construction, not immutable, and thus should not be reified. Putting all men or all women into one box, unfortunately, does exactly that. As the example of the introduction attests, though, men are not a homogenous category, and male icons are subject to change.

Coming from necessity or conviction, 4B has influenced modern Korean society and recent worldwide discussion, yet has not become a mass movement. What it depicts is an image of a patriarchal society whose inflexibility has been the cause of concern for many women. The question is whether patriarchal inflexibility can be answered by an equally inflexible—although non-harmful, unlike misogynist acts—stance on life.

References

- The 4B Movement: Radical Feminism, Social Resistance, and Global Impact (Part I). Mondo Internazionale. Available here

- From country to country: 4B movement reshapes today’s feminism. Daily Illini. Available here

- A woman is not a baby-making machine’: a brief history of South Korea’s 4B movement – and why it’s making waves in America”. The Conversation. Available here